A mine, a mill and a mystery

Mancos pieces together clues from shuttered gold operation

by Paul Ferrell

Residents of Mancos are at the center of a mystery as they await results of an environmental study on an illegal mining operation.

“I’m scared,” says Camill Begay who lives with her three children 100 yards downwind from the Red Arrow Gold Corp.’s illegal mercury amalgamation gold mill in Mancos. The mill was shut down June 18 because it was a hazard to public health and was operating without a permit. Equipment and tailings at the mill contained elevated levels of mercury and arsenic according to a report by the Division of Reclamation, Mining and Safety (DRMS) released Aug. 1. “I used to take walks down there with my kids in the evening,” says Begay. “It’s scary.

|

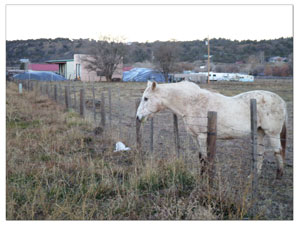

| A horse grazes in a pasture with the “winterized” tailings piles of the defunct Red Arrow mill in the background on Nov. 5, a week after the EPA conducted soil and air testing of the area. On Nov. 6, animals had been removed from the pasture and have not returned./Photo by Paul Ferrell |

The Red Arrow Gold Corp. has owned and intermittently operated the Red Arrow Gold Mine, 9 miles northeast of town, since 1988. But the Colorado Department of Natural Resources found 11 violations at the mine and illegal mill last June and enacted an emergency shut down.

In addition to the hazardous materials, the DRMS report shows incongruities at the mill, which lead some to believe that the now-bankrupt corporation was also attempting to defraud investors.

The report shows that approximately 250 cubic yards of mine tailings were found at the mill site in town and 5 cubic yards were found at the Red Arrow Mine, a separate facility 9 miles northeast on the western flanks of the La Plata Mountains. At both locations, mercury and arsenopyrite, an arsenic ore, were detected in the tailings. One building at the mill, dubbed the “mercury building” by investigators, was found to have high concentrations of mercury adhering to the walls and a container labeled “21.5 pounds mercury.”

It is believed this is where the mercury amalgamation took place, whereby gold is separated from the ore using mercury as a vehicle. Once infused with gold, the mercury is heated – in this case with a kiln – and vaporized, leaving the gold behind.

According to the World Health Organization, the inhalation of mercury vapor can produce harmful effects on the nervous, digestive and immune systems as well as lungs and kidneys, and may be fatal. “Mercury is something that I don’t think has been used on any sort of commercial scale for many, many decades,” DRMS’s Senior Project Manager Steve Renner said.

The Red Arrow mill’s makeshift system for collecting mercury vapors from the kiln featured an inverted galvanized bucket connected to metal ducts. Jim Law, leader of the independent fact-finding Mancos Environmental Awareness Group (MEAG), called the system, “Mickey Mouse.”

Law is especially concerned about the five or six individuals who might have worked inside the mercury building. “I’d love to get the people that worked in the plant to get tested,” he says.

Without proper precautions like scrubbers and hazmat suits, Renner says mercury contamination could affect the workers and be brought home. “Hypothetically an employee that goes home to his house and takes his contaminated clothing off ... there might be an elevated level in that particular family’s home,” he says. Neither hazmat suits nor mercury scrubbers were found on the property. The lack of safety measures has members of MEAG concerned.

For starters, the kiln used to heat the mercury is beside a window, which is situated next to a livestock pasture. “There’s a pasture directly adjacent to the east of the property, followed by a trailer park, followed by the town,” Travis Custer, from MEAG, says. “It’s a fairly windy place.”

Dr. Lyn Patrick, a naturopath and expert on metal toxicology, says there are not just concerns with the mercury but the arsenopyrite as well. “Arsenopyrite is iron ore and arsenic together,” she says. “When it is heated to high temperatures ... the arsenic disassociates with the iron and becomes airborne.”

The tailing piles are stored outdoors at the mill where they have been subject to oxidation, a potentially dangerous situation. “The arsenic oxidizes and in that process can be freed from the arsenopyrite, and then it’s available as a toxic form of inorganic arsenic,” she says, adding that inorganic arsenic can then be transported by the wind.

On Nov. 1, the tailing piles at the mill were stabilized for the winter by the DRMS. “They covered it with PVC membrane, essentially sealing it, to prevent it from blowing away,” says Custer.

Steve Merritt, from the Environmental Protection Agency, had a crew testing soil and air around the mill site Oct. 28. Merritt notes that beef cattle were grazing near the mill in the pasture to the east. “I don’t anticipate they would have a significant (mercury) uptake,” he says.

However, Dr. Patrick says the cattle could pose a hazard to people. “In humans, mercury accumulates in the central nervous system and the kidneys and in the liver,” she says. “If (the cattle) were exposed to mercury, then people would be eating tissues that may or may not, depending on the exposure, have high levels of mercury in them.”

The preliminary results from the EPA tests are expected back this Fri., Nov. 15, and will be shared with MEAG as well as Montezuma County Health personnel, says EPA’s Merritt. The full EPA report, with the soil and air test results, will be released to the public by Dec. 1.

“Once that soil testing report is published, then we’ll know what kind of further actions are going to be taken,” says Dr. Patrick.

|

| A backhoe sits outside Red Arrow Gold Corp.’s so-called “mercury building,” where it is believed mercury amalgamation was used to try to extract gold from ore. The mill was shut down due to several serious health violations. A tailings pile sits under the plastic tarp to the right./Photo by Paul Ferrell |

Members of MEAG believe the key to determining the health risks lie in testing the individuals who worked inside the mercury building. “The workers have not come forward in order to get tested yet, probably they will not, because many of them are related to the gentleman who owns the mill and the mine,” Dr. Patrick says.

Merritt says he believes the workers might be reluctant to come forward given liability or other things they might face if they identify themselves. “It sounds to me like they’ve been paid somewhat under the table and off the radar of various revenue agencies,” says Merritt.

This is not the only mystery surrounding the operation. The Aug. 1 report released by the DRMS shows several factors that deserve scrutiny. “This starts to get into areas of conspiracy theory,” says Law.

For starters, the container labeled “21.5 pounds mercury” was found to actually contain no traces of the dangerous metal. Furthermore, Renner is curious about a large pile of “cross cut” – material barren of ore – found at the mill. Merritt wonders why it would be moved 9 miles from the mine to the mill. “There’s no viable economic reason to move that material to a mill site because it doesn’t have any ore value,” he says. “So there’s no real benefit other than to show people that something’s happening ... they wanted to show progress or demonstrate that some activity was going on at the site to substantiate that fact that they were still working on making investors money.”

Although no formal investigation is under way, Law, Merritt and Renner see possible fraudulent actions on the part of Red Arrow president Craig Liukko. “I don’t know if that was DRMS’s take on it as well, but that was definitely our impression,” said Merritt. “They were not doing a whole lot of mercury amalgamation work in my estimation.”

But this is where the plot thickens. If there was less milling activity than originally thought, why were mercury-laced tailings found at the mill and the mine? “All the mercury equipment that was discovered was discovered at that warehouse in Mancos,” Renner says. “So there’s no evidence that he did any mercury work up there at the mine site itself. It appears that they hauled (the tailings pile) from Mancos up to the mine site and stored it in that building.”

The building is about 80 feet from the East Fork of the Mancos River. One theory is that the mercury-laced tailings were hauled back to the mine to be disposed of in the East Fork. “The East Mancos River is dead, meaning that there is no aquatic life in it,” says Law. Because of this, it is likely that no one will ever know if it was used as a disposal site.

Fortunately, the water for the town is taken out of Jackson Lake, which is fed by the West Mancos River and is not affected. However, the East Mancos does affect farmers who are tied into it for watering crops, Law says.

Liukko did not immediately return calls for comment, and Red Arrow Gold Corp.'s former office on Grand Avenue in Mancos has been leased to another company. However, in a story in the Denver Post last July, he admitted to building an unpermitted gold mill and using mercury without permission but denied creating any environmental dangers or violating state regulations. “We are very, very responsible environmentally,” Liukko told the Post.

The company's website states that Red Arrow Gold Corp. is in the business of developing "safe, efficient and environmentally responsible mining and mineral processing" and that the Red Arrow Mine is the "working model for future organic growth."

Plans called for processing up to 20,000 tons of ore annually at the mill site, according to the web site. Records found by inspectors in a Red Arrow building showed that in recent times, the mine had been producing 1 to 2 ounces of gold per day.

Meanwhile, residents of Mancos await the EPA report due around Dec. 1. Mancos Town Administrator Andrea Phillips is expected to convene a community meeting to discuss the report at that time.

Dr. Patrick is cautious about sounding the alarm before all the facts are fully known. “I’m very, very, concerned, but telling the town that they’ve been mercury poisoned and they all need to get tested, that’s not ethical until there’s evidence that this actually happened. Once we get evidence that that’s actually what happened, then you better believe I will do that.”

In this week's issue...

- January 25, 2024

- Bagging it

State plastic bag ban is in full effect, but enforcement varies

- January 26, 2024

- Paper chase

The Sneer is back – and no we’re not talking about Billy Idol’s comeback tour.

- January 11, 2024

- High and dry

New state climate report projects continued warming, declining streamflows