|

|

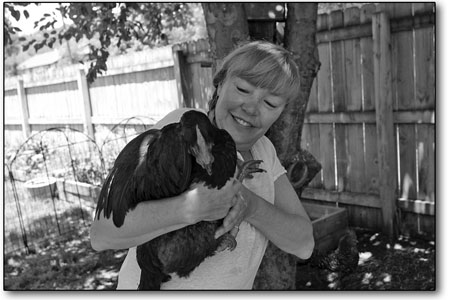

Tamsen Wiltshire, who offered a workshop on raising chickens during the Tour de Coops last year, has three chickens, which she keeps in her back yard off 32nd Street./Photo by Steve Eginoire |

All cooped up

Reconciling residents’ and wildlife’s love for backyard flocks

by Page Buono

Since the passing of the City of Durango’s chicken ordinance in 2008, the local “coop culture” has been on the rise. But as the numbers of backyard foul increase, so does the risk of attracting uninvited houseguests, notably bears.

Since the passing of the City of Durango’s chicken ordinance in 2008, the local “coop culture” has been on the rise. But as the numbers of backyard foul increase, so does the risk of attracting uninvited houseguests, notably bears.

But just how many are jumping on the chicken bandwagon is hard to gauge. The ordinance, which allows city residents to keep up to six hens and roosters younger than 6 months, requires chicken owners to register their brood with a $20 fee and a coop inspection. The ordinance also outlines requirements regarding coop structures and general management of the chickens.

However, as evidenced by the four people registered this year, registration is seldom adhered to, making it nearly impossible to track the real number of poultry in Durango.

But if participation and interest in local chicken-themed events is any indicator, Durango is cuckoo for its chickens.

“It’s been really interesting to see how many people have chickens and the different set-ups and styles,” Managing Director of Local First LeeAnn Vallejos said of the organization’s annual Tour de Coops. “There are tons of people in Durango who have them.”

And for most, the chickens are more than an easily available food source. Tamsen Wiltshire, who offered a workshop on raising chickens during the Tour de Coops last year, has three chickens, Mimi, Blue and Layla, which she keeps in her back yard off 32nd Street. You might call the hens spoiled – a coop with flower boxes, shade under an apple tree, a dirt bath and an all-organic meal plan.

“Blue’s the smart one, Mimi’s the good looking one, and Layla’s tame,” Wiltshire said.

|

| Chickens can live anywhere from 12 to 20 years, though most stop consistently producing eggs around the age of 3 or 4./Photo by Steve Eginoire |

On the other hand, Vallejos, who also has chickens, takes a more practical approach. She names all of hers Rosa to keep things simple.

Others, still, take a step in the other direction, treating the chickens as bonafide members of the family.

Jill Southworth, a county resident living near Turtle Lake, originally got chickens so she could teach her kids more about food, allowing them to be closer to the source. However, she often lets her poultry-mates wander the house, or sleep by her side.

And while a local poultry census remains elusive, local wildlife appear to be keeping track. Although bears are often mentioned as the biggest threat, many owners say raccoons are, by and large, the biggest problem.

Southworth lost two ducks and one chicken to a raccoon last year. She ended up killing it with a BB gun and leaving the carcass outside her property in the “pile of shame” to ward off future intruders.

Vallejos said although their are bears in her neighborhood, they have not proven to be a problem yet. “It’s the raccoons. They’re hungry and wily and they massacre them,” she said.

However, according to Bryan Peterson, of Bear Smart Durango, 82 bears were put down by wildlife officials last year, the most in more than a decade. Peterson fears that the added attractant of urban chickens will only make this number rise in coming years.

Bears in Durango are essentially on a two-strike policy: after one report for an incident in which a person or property is damaged, they are relocated. But unfortunately, relocation generally does more to appease the public than it does to save the bears, as most bears return to their home territory, sometimes faster than the ranger’s truck, he joked. If they are reported again for threatening behavior, they are killed.

“The city allowing chickens places additional stress on Colorado Parks and Wildlife,” said Peterson.

While the consensus is generally that raccoons and dogs are the biggest threats to chickens, bear attacks do occur. Peterson said he regularly receives reports, if even just from friends on Facebook, of bears raiding coops and slaughtering chickens. While raccoons and dogs can be kept at bay most of the time, with sturdy fences and solid coops, bear attacks are nearly impossible to thwart.

He says “nearly impossible,” because there is one weapon in the line of defense that appear to be working: electrical fencing. At a recent Bear Conference in Missoula, Mont., Peterson learned that electric fences are being touted as by and large the most effective deterrents for bears, and he is urging locals to take the responsible step. However, before that can happen, he acknowledged there are some logistical and legal barriers that must be crossed.

Currently, city code does not allow electric fencing (or barbed, or razor-edge fencing for that matter). But, according to Peterson, the city has made some exceptions for individuals using electric fencing to protect their chickens.

Peterson said that climate and drought conditions are going to continue encouraging bears to move into town, and that the best thing the city can do is allow people to use electric fences to protect their chickens.

Aside from electrical fencing, Southworth, Wiltshire and Vallejos also say a strong, “wildlife-proof” enclosure is key to happy chicken rearing. In addition, they offer a few tips of their own:

- To buy chickens locally or for general advice, ask Con Kemple, at Farmer’s Supply on Sawmill Road, or Ashlie Hall, at Mesa Market at Elmore’s Corner.

- Find out ahead of time what food isn’t good for chickens: avocadoes, raw potatoes and chocolate to name a few.

- Provide an area for a dust bath, a mix of dirt, ash and oyster shells to help repel bugs and mites.

- Start small, begin with two or three chickens to work out the kinks.

- Chickens need 12 hours of daylight to lay their eggs; heat lamps in the coop in the winter help achieve year-round production.

- Chickens like to roost, so if you come home one day and your chickens are nowhere to be found, look up. Vallejos found hers in the trees and had to climb a ladder to retrieve them.

- Chicken compost is magic for gardens. Wiltshire uses a tumbler purchased at Kroegers for $189 to produce her compost.

- For a little wholesome entertainment, Southworth recommends feeding spaghetti to the chickens.

- Handling the chickens at an early age helps make them more well-behaved, approachable and even cuddly later on in life.

According to the trio, raising chickens is easy-peasy. Southworth, Wiltshire and Vallejos all reported spending less than $30 a month to maintain their chickens, with a start-up cost of anywhere between $200-$500, depending on the coop. And, with chickens producing at least an egg a day, none of them ever buy eggs and give away nearly 50 percent to friends or neighbors.

For many chicken owners who adore their egg-laying yard mates, the issue of what to do with the chickens when they stop laying can be a little tricky. Chickens can live anywhere from 12 to 20 years, though most stop consistently producing eggs around the age of 3 or 4.

While neither Southworth nor Wiltshire intend to consume their poultry pals, Vallejos intends to bring the cycle of life full circle. However, since there is no processing plant nearby, she intends to do it the old-fashioned way, with the help of a friend who has slaughtered chickens before.

“I guess it’s just part of the process,” said Vallejos. While she admitted to being slightly nervous, perhaps this is where Vallejos’ more matter-of-fact approach to chicken farming comes in handy. “We love watching our chickens,” she said. “But I wouldn’t say we’re super attached.”

Alas, whether they end up under the kitchen table or on top of it, Southworth said the most important thing is to make the most of your time with your birds while you have them. “Love your chickens!” she said. “They’re so much fun!”

To find out more about registering chickens or the local ordinance, go to www.durangogov.org/index.aspx?NID=253.

To report bear activity, both sightings and violations, please contact 247-0855.

In this week's issue...

- January 25, 2024

- Bagging it

State plastic bag ban is in full effect, but enforcement varies

- January 26, 2024

- Paper chase

The Sneer is back – and no we’re not talking about Billy Idol’s comeback tour.

- January 11, 2024

- High and dry

New state climate report projects continued warming, declining streamflows