|

| ||

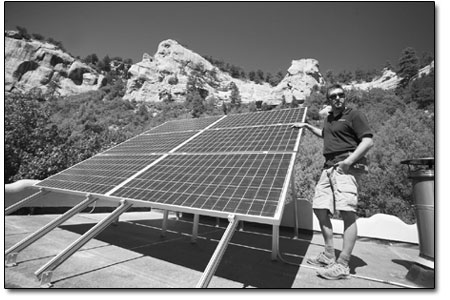

| A shot in the arm for solar

by Missy Votel

Known as a feed-in tariff, the idea was first introduced in the United States in the 1970s. The ensuing crash in the oil market in the 1980s, as well as a change in presidential administrations, killed the idea here. But it was picked up overseas, particularly in Europe, where feed-in tariffs have been met with widespread acceptance and success. Despite its name, the feed-in tariff is not a tax, but a premium paid to small- and medium-scale producers of renewable energy. Unlike the “market-based” renewable energy credits offered by utilities today, feed-in tariffs don’t fluctuate over time, but are fixed over a period of several years. “In a nutshell, it’s an economic policy that guarantees the price for a unit of generated energy or power for a certain amount of time, usually 20 years,” said John Lyle, a Durango electrical engineer who is helping re-introduce the idea locally. Fixing the price is important because it allows citizens installing renewable systems – such as solar, wind, microhydro or biomass – to know how soon they can recoup their costs. By remaining stable, the cost, which is based on the cost of equipment, also acts as an incentive, assuring people they will eventually break even, and might start making money. “The idea is you are a power plant, you are supplying the power to the electrical grid,” said Derek Wadsworth, with Solarworks, a Durango installer of renewable energy systems. “With feed-in tariffs, people can really get a better idea on their pay back on a system.” Currently, La Plata Electric Association pays owners of photovoltaic systems 70 cents for every kilowatt hour of energy produced. However, this cost is set to drop to 50 cents next year, and then drop by another 10 cents for every year thereafter. Wadsworth said for the average 4 kilo watt system on a smaller home, which runs about $24,000 before rebates, this amounts to a $2,800 rebate this year, $2,000 in 2011, $1,600 in 2012 and so on. This puts the possibility of ever fully recovering the cost of the system further out, thus discouraging many would-be power producers. “The (renewable energy credits) really hurt people trying to figure out payback on their systems,” he said. “Feed-in tariff’s are sort of like the difference between investing in a longterm CD, where you know your money will be safe, and a risky stock,” he said. Aside from the security feed-in tariffs give renewable-system owners is the security they would lend to the local economy. According to Lyle, the Southwest, with its abundant sunshine, is ripe for solar-power generation. “We are blessed with an extraordinary amount of solar resources in the Southwest,” he said. “By producing solar energy, we don’t destroy the Earth. It’s a sustainable resource and it makes for a sustainable economy.” According to Lyle, by encouraging renewable energy through feed-in tariffs, the United States can insulate itself from the volatility of foreign and national energy prices while ensuring plentiful, clean power. However, feed-ins can also strengthen local economies by keeping profits and control over energy sources local instead of going to some out-of-state corporate entity. In addition, it can help diversify sagging sectors of local economies, for example by allowing ranchers to install photovoltaic collectors on the same land they use to graze cattle. Any system producing less than 20 megawatts is considered “distributed level,” which means it ties into the local grid. As such, any excess energy produced goes back onto the local grid to the next stop down the line. “The power you’re not using goes to your neighbor’s house or the next house on the grid,” said Wadsworth. “This way, we know the power and money made off it stays here.” In contrast, “green power” blocks now available through LPEA don’t actually come directly from green energy. Rather, the money paid for green blocks is used to invest in renewable energy projects, such as a wind field in Wyoming. But local energy still comes from coal plants owned by Tri-State Generation. Furthermore, with LPEA’s recent reduction in the cost of green power blocks from 40 cents to 10 cents a kilowatt hour, there is now less money available to invest in such renewable projects, Wadsworth said. However, feed-in tariffs will level this playing field. “No matter what you’re generating, you should be seen as an equal power generator as the coal-fired power plant,” said Wadsworth. Of course, the success of feed-in tariffs not only requires the buy-in of LPEA customers but LPEA itself. On Wednesday, the San Juan Citizens Alliance and the Sustainability Alliance of Southwest Colorado sponsored a series of talks and workshops on feed-in tariffs, including a presentation to LPEA board members. The events featured Paul Gipe, an author and expert on alternative energy. According to Lyle, the object was to introduce the idea to the local community as well as LPEA. He said some LPEA board members have already expressed interest in the idea and want to learn more. However, he noted that widespread policy changes such as this are often slow in coming. “We are beginning at the bottom of a long educational curve,” he said. “Americans haven’t even heard the term. It’s going to take a while to educate people, but I think when they understand, the idea will catch on.” He also said that the argument that feed-in tariffs will raise electricity rates is short-sighted. He said with the current cost of coal-powered plants, environmental controls and large-scale transmission, power rates are going to go up regardless. Eventually, however, there will come a breaking point, where renewables become cheaper than carbon-based fuels. Furthermore, feed-in tariffs have already proved successful in several European countries, most notably Germany. Since feed-in tariffs were launched there a decade ago, 300,000 new jobs have been created as a result, and in the first six months of this year, Germany installed twice the solar photovoltaic systems installed in the United States over the last 20 years. Several U.S. cities and states are also exploring the feed-in option, including: Gainesville, Fla.; Sacramento, Calif.; Washington State; Vermont; Michigan; Minnesota; the State of California; and Hawaii. The idea has also caught on along the Front Range of Colorado, but Lyle believes LPEA’s participation could make it a leader in the state. “I am very optimistic,” he said. “It’s time to get this country going again from the grassroots up.” Wadsworth agrees that once residents and LPEA understand the benefits, they will climb on board. “Once they learn about it, people will want to do this because it’s the right thing to do. You can’t spill clean energy,” he said. “Plus, you can make money, feel good about the environment and help our community become a better place to live. We should all become energy exporters. We have a lot of empty rooftops and fields. Cover them with panels.” •

|

In this week's issue...

- May 15, 2025

- End of the trail

Despite tariff pause, Colorado bike company can’t hang on through supply chain chaos

- May 8, 2025

- Shared pain

Dismal trend highlights need to cut usage in Upper Basin, too

- April 24, 2025

- A tale of two bills

Nuclear gets all the hype, but optimizing infrastructure will have bigger impact

A local group of renewable energy advocates is working to shed new light on a relatively old idea they say will lead the way to sustainability and a stronger economy.

A local group of renewable energy advocates is working to shed new light on a relatively old idea they say will lead the way to sustainability and a stronger economy.