|

| ||

| Big Ag smackdown

by Ari Levaux

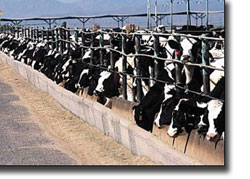

The rule closes loopholes that mega-dairies have used to exploit the organic market, a $24.6 billion industry. Access to Pasture mandates that meat and dairy cattle branded organic must graze for a minimum of 120 days on pasture. At least 30 percent of the animals’ total annual caloric intake must come from grazing. The rule leaves one significant question open with regard to meat production: whether beef cows should be exempt from these grazing requirements before being slaughtered. A 60-day comment period closes April 19. The new rule is a blow to mega-dairies that for years took advantage of the previous requirement of “access to pasture.” The real-life manifestation of this ambiguous phrase was often a warehouse door open to a muddy yard. Clarifying “access to pasture” has been under discussion between the National Organic Program (NOP) and USDA since 1994, and a rule similar to the new rule was first proposed in 2005. It languished in Bush’s USDA for a variety of reasons that are currently under investigation. When the draft was opened for public comment, 80,327 were lodged. All but 28 favored clarifying the phrase. In addition to clarifying pasturing requirements, Access to Pasture tightens up other cracks in the federal definition of organic. It expands and strengthens the language prohibiting antibiotics in organic feed, requires that edible bedding (like straw and corn cobs) be certified organic, and mandates pasture be managed as a crop. Access to Pasture tightens up other cracks in the federal definition of organic. It expands and strengthens the language prohibiting antibiotics in organic feed, requires that edible bedding (like straw and corn cobs) be certified organic, and mandates pasture be managed as a crop.Much of the new 160-page rule consists of comments, that are parsed into arguments for and against the rule. Of the 26,970 comments USDA received, 26,000 supported more pasture time for organic cattle. All but 130 of the comments arrived via three modified form letters. Many small-ag types were skeptical of Obama’s appointment of former Iowa Gov. Tom Vilsack as Secretary of Agriculture. Vilsack’s cozy relationship with corporate agribusiness earned him “Governor of the Year” kudos from the Biotechnology Industry Organization. One of Vilsack’s first moves was to install an organic garden in the plaza in front of the USDA building in Washington. He then recommended all USDA facilities around the country do the same. Then Vilsack appointed Kathleen Merrigan as deputy administrator, the USDA’s No. 2 spot. She’s credited with writing the Organic Foods Production Act of 1990. While organic cheerleaders appear to have much to celebrate, some unfinished business will soon tell us more about which direction the USDA is really headed. Public comment just ended on the USDA’s determination that Monsanto’s GE alfalfa meets USDA standards. The decision came despite the agency’s admittal that GE alfalfa is likely to cross-contaminate with non-GE alfalfa. Not one comment in an online survey favored approving the GE alfalfa. The response to these comments could create a showdown between Vilsack’s biotech interests and the newly comment-friendly agency he leads. Another looming question is what will replace the National Animal Identification System (NAIS) proposal, which was scrapped in another victory for small ag. NAIS would have forced all livestock farmers great and small to keep painstaking and expensive records of their animals. And finally, the burning item of business that Access to Pasture leaves unresolved for another 60 days: “We are requesting comments on the exceptions for finish feeding of ruminant slaughter stock.” As it stands, the USDA exempts beef cattle from the requirement that 30 percent of nutrition come from forage for 120 days prior to slaughter. In practice, this allows organic beef cattle to be confined and fed grain for four months prior to slaughter, known as feedlot finishing. Access to Pasture notes, “The sentiment among most of the commenters is that there is no place in organic agriculture for the confinement feeding of animals nor should there be any exception for ruminant slaughter stock.” If that sentiment holds, the organic feedlot exception should end. But if “organic” beef is allowed to be “finished” in confinement, that would not only cast doubt on what appears to be a newly democratic USDA, it would violate several key aspects of organic livestock production. Plus, feeding them grain not only produces a different kind of meat that’s less healthy, it’s much more energy-intensive and environmentally destructive. Perhaps the real discussion shouldn’t even be about whether organic beef cows can be confined and grain fed for the last 120 days of their lives. The discussion should be about whether organic cattle should be fed any grain at all. •

|

In this week's issue...

- January 25, 2024

- Bagging it

State plastic bag ban is in full effect, but enforcement varies

- January 26, 2024

- Paper chase

The Sneer is back – and no we’re not talking about Billy Idol’s comeback tour.

- January 11, 2024

- High and dry

New state climate report projects continued warming, declining streamflows

Small-ag and organic watchdog groups found themselves in terra incognita recently: cheering the USDA for tightening definitions of organic meat and dairy. On Feb. 12, the agency published “Access to Pasture,” a “final rule and request for comments” regarding organic standards for livestock. It’s been called the most sweeping rewrite of federal organic standards since their inception in 2002.

Small-ag and organic watchdog groups found themselves in terra incognita recently: cheering the USDA for tightening definitions of organic meat and dairy. On Feb. 12, the agency published “Access to Pasture,” a “final rule and request for comments” regarding organic standards for livestock. It’s been called the most sweeping rewrite of federal organic standards since their inception in 2002.