|

| ||||

| The winter locavore

by Amy Donahue

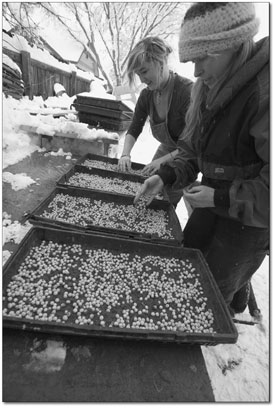

The Durango local food movement has grown exponentially in the last several years, a self-fulfilling cycle of more fervent demand and an increasingly diverse supply. However, the key to success of the local food movement is year-round consumption. As the winter months set in and access to local growers becomes less regular, Durango locavores tend to return to a dependence on foods from thousands of miles away. Breaking this cycle, local growers say, requires moving toward a pattern of seasonal eating. “When winter comes and you are used to planning meals according to what you feel like eating, you’ll probably grab those South American peppers or Florida-grown zucchinis that have traveled umpteen thousand miles,” said Dixie Neumann, of Heartwood Farms, a component of the Heartwood Co-Housing community near Bayfield. “But when you’ve eaten fresh and local long enough, you can truly tell the difference … in how vital your body feels and in the clarity of your mind.” According to Katrina Blair, of Turtle Lake Refuge, much of the responsibility for eating locally lies with individuals. This requires a shift in mindset, based on seasonal eating habits and fall preparation for the winter. Canning, freezing and drying are all fairly easy methods of food preservation and provide a way to eat summer foods in the winter months. The cold weather itself can be put to use in creative outdoor freezer designs. In addition, Blair said buying grains in bulk to sprout is an easy way to grow greens. This can be as simple as sprouting grains in a jar in a sunny window. “You can take it a step further by planting seeds in dirt, and in two weeks, you will have a full garden you can harvest,” she said. “You just need one shelf in the kitchen to grow fresh salad greens." Terry Woodward, outreach coordinator for the Sustainability Alliance of Southwest Colorado and design coordinator for the La Boca Center for Sustainability, said that one of the goals of SASCO is to educate urban and suburban dwellers on ways to use cold frames (small greenhouses) and convert basements or crawlspaces into root cellars. Durangoans looking to continue their commitment to local food through winter can easily include these traditional techniques of food storage, but true food security will require a larger stash of winter staples such as root vegetables, squash, sprouts and animal products. Although always key to winter survival on farms and in remote places, root cellars are taking on a new and larger role as local farmers think about supplying food year-round. Neumann said the main goal of Heartwood Farms this year is to provide a four-season food source for the 80-member community. Although selection may be slimmer in winter, Heartwood boasts an innovative root cellar that maintains temperatures in the mid-30s and is big enough to store crops to supply Heartwood as well as local stores and restaurants. Another facet of supplying food in the winter is the ability to grow cold-tolerant vegetables like greens, sprouts, and in the case of Heartwood, even peppers and tomatoes. The La Boca also makes use of these techniques, but still cannot guarantee a year-round supply for public consumption, Woodward said.

The La Boca also makes use of these techniques, but still cannot guarantee a year-round supply for public consumption, Woodward said. Innovative ideas are required to ensure the food security of the Durango community. Woodward said when grocery shelves were startlingly empty during the snowstorms of winter 2007-08, Durango’s dependence on distant food sources became obvious. Woodward added that the last couple summers have verified community interest in year-round consumption of local foods and goods, and this success is sparking ideas to fill the winter void. One idea is to expand La Boca’s Community Supported Agriculture program, or CSA, to year-round enterprise that would include root crops, cheese and eggs, as well as a snow-bound food box that would include items like Dove Creek beans, dried meat and fruit, and canned goods. “More resilient and innovative ideas like these will help create a more distributed food supply that will, in turn, create a more food-secure community,” he said Ultimately, said Woodward, the goal is a more evenly distributed food supply based on individual responsibility for food production and storage, as well as community warehousing and inventory. Woodward said his hope for the future is a centralized facility where farmers can bring their raw products for processing and packaging. This idea is central to winter consumption of local foods but may prove challenging because of health and safety regulations. Cindy Dvergtsen, of Arriola Sunshine Farms, outside of Dolores, said her ability to supply the larger community with food over the winter would be directly related to access to such a facility. Although Arriola Sunshine Farms sells lambs and turkeys, customers are responsible for their own meat processing. The same idea applies to winter supplies of fruits and vegetables. Dvergtsen said a centralized washing, packaging and cold-storage facility would greatly enhance local farmers’ abilities to provide winter produce. Woodward described this facility as an opportunity for some enterprising individual. It could serve as a co-op processing facility that would in turn sell to the general public as well; or it may simply be a step in the process, which would then supply stores that would offer the locally made items. In either case, there is a perceived need that must be fulfilled in order to seize the potential of area growers to provide a year-round supply. “We need entrepreneurs and marketers to be involved in developing these other segments of the food supply chain,” Dvergtsen said. “Southwest Colorado has good climate, soil and water, which means that we can feed our area very well and also export food to the region and beyond. If we had washing, packaging and cold storage facilities, we could produce more fruit, eggs and vegetables for local consumption year around. If we had state-inspected poultry processing, we could supply fresh turkey and chicken year round.” Heartwood’s Neumann said she is convinced that the growing cycle of supply and demand will help make year-round local food a possibility. “As we, the consumers, begin to demand that our food be of the freshest quality, grown in the same soil that we live and play on every day – the soil that we have ‘planted’ ourselves in – I guarantee that the farmers will be only too happy to find ways to get that food to you,” she said. “As consumers pledge their support for local food year round, farmers will feel confident enough in their market to make it happen.” •

|

Imagine a cupboard packed with neatly labeled jars of beans, pickles, jam and chutney; a freezer full of locally raised beef, lamb, turkey and raspberries; a root cellar stuffed with potatoes, onions and pumpkins. This is the image of abundance, of food sustainability, of the future of the local food movement as it expands to envelop the winter months.

Imagine a cupboard packed with neatly labeled jars of beans, pickles, jam and chutney; a freezer full of locally raised beef, lamb, turkey and raspberries; a root cellar stuffed with potatoes, onions and pumpkins. This is the image of abundance, of food sustainability, of the future of the local food movement as it expands to envelop the winter months.