| ||||

A wild education

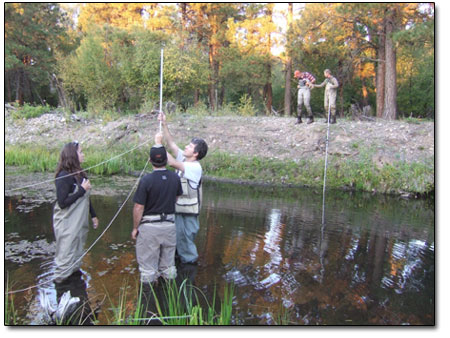

by Will Sands The field became the classroom for 18 Fort Lewis College students this fall. “Wildlife Ecology & Management,” a senior level class, took students out of the classroom and literally got their feet wet in the great outdoors alongside working field biologists and ecologists. When it came down to it, the students’ biggest tests may have been trapping bats, electroshocking trout or taking hantavirus precautions when handling small mammals.Erin Lehmer, assistant professor of biology at Fort Lewis, hatched the class as a way to get would-be scientists out in their future element. “Wildlife Ecology & Management” was specifically geared toward environmental biology majors transitioning into higher studies or careers in wildlife biology and ecology. Eric Falk is a senior at Fort Lewis College who hopes to take his degree into a career in marine conservation and reef restoration. For him, getting out of the lab and onto the ground provided an invaluable look at the way biologists really work. “It’s definitely a very unique class,” he said. “For me, it opened a lot of windows and doors into other aspects of biology as opposed to just sitting in the classroom or leafing through books.” One key to the class’ success was forging strong partnerships with individuals and agencies and giving the students a taste of the real-life work that awaits them. “The unusual thing about this class was that a lot of it was field based,” said Lehmer. “It’s a class that’s based in advance topics in ecology that have a specific focus in wildife.” During the course of the semester, students examined a variety of topics ranging from animal behavior and habitat fragmentation to wildlife law and environmental policy. In addition to exploring books and multimedia, students found themselves in a variety of unusual classrooms. One session with the Division of Wildlife was devoted to electroshocking trout in order to complete fish counts. In another, they captured bats and conducted a count of local populations. Later in the semester, they traveled south to the Durango Nature Center to net and band birds. For the final project, each student was required to write up a hypothetical biological assessment. One member of the class conducted an exhaustive field study in Horse Gulch and examined the impacts of potential development there.

“I’d say that the class was an absolute success,” Lehmer said. “These experiences were incredibly valuable and taught the students a lot. One of the biggest successes was that they were able to work so closely with working wildlife biologists and get a sense for what these careers are actually all about.” The DOW was a major partner in the class, and its field officers took a great deal of time out of busy schedules to help on a variety of fronts. Colorado Wild and Great Old Broads for Wilderness also offered a hands-on look at wildlife conservation, and the Nature Conservancy and San Juan Citizens Alliance gave presentations on two very different approaches to wildlife activism. “It took a huge effort on the part of these agencies and organizations,” Lehmer said. “They put an enormous amount of time and effort into something that’s not in their job descriptions.” The San Juan Institute, a nonteaching department at Fort Lewis College, also partnered in the effort. The Institute was established as a way to bring community members and agencies together around research projects. Lynn Wickersham, an ornithologist with the Institute, conducted one of the class’ field labs. The experience brought back memories for the scientist. “Having been a biology student, there are so many different sub-fields out there,” she said. “For a student looking for a career in science, trying different things and seeing what’s involved is invaluable.” Consensus building was a key feature of the class, according to Lehmer. Wildlife issues are never cut and dry, she said, and never as simple as conservation vs. development. “We really took a hard look at the importance of building consensus and getting all of the different stakeholders involved,” Lehmer said. “For instance, what common ground can we find with someone like a rancher who has a long history of conflict with wildlife. The flip side is that rancher is supplying open space and habitat, and that we actually have common goals. We wanted to look a these kinds of things on more than a superficial level.” One interesting twist in “Wildlife Ecology & Management” was that each student, as well as Lehmer, was required to obtain a Colorado Hunter Education Card. Lehmer noted that the Division of Wildlife is responsible for most of the wildlife management in Colorado, and hunting and fishing fees fund that effort. She added that every biologist should look at wildlife issues from the other end of the barrel. “The earliest conservationists were sportsmen groups,” she said. “Plus, the fact is that revenues from hunting licenses account for a big chunk of wildlife management in Colorado. Students need to know how to communicate with these stakeholders.” These students may also be at the forefront of global issues in coming years. Concerns like climate change and mass extinction promise to be more than headlines in coming years and decades. The world will need strong leaders from the scientific community, according to Wickersham. “We have so many challenges now with climate change and dwindling natural resources and expanding urban and suburban growth,” she said. “It’s vital for our future that as many people are educated on these issues as possible.” •

|