|

| ||

| New power for the San Juans

by Allen Best

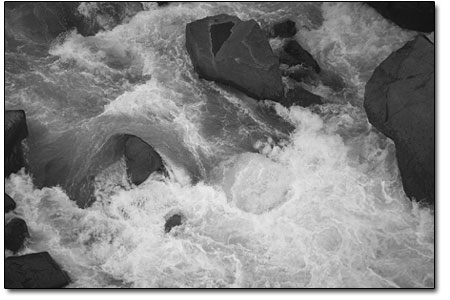

The electrical production will be relatively small, 22 kilowatts, but enough to power the pumps used to circulate water at the nearby Ouray Hot Springs Pool. It is, in the eyes of Bob Risch, the mayor of Ouray, a start of what he hopes to see more broadly – not just in Ouray, but across the San Juans and beyond. “A bunch of small facilities like this can add up to a significant contribution,” says Risch, an astronomy teacher now retired in Ouray, where he was born and raised. With access to seed money through the federal stimulus program, many small governments and some individuals have been taking a new look at small hydro across the Colorado Rockies and more broadly across the West. A forum held in Ouray during June drew 100 people, and a similar session held in Durango recently attracted 50 participants. The potential is great. In a broad-brushed survey conducted several years ago, the Idaho National Laboratory concluded that 1,800 megawatts of electricity could be produced within Colorado without invading wilderness, roadless or other sensitive areas. This compares with the 1,500 megawatts output from the proposed Desert Rock coal-fired plant in New Mexico. More selectively, Colorado energy officials did a quick study of 100 sites, with potential for 100 megawatts – without building new dams, they hasten to add. Congress has also started paying attention. A subcommittee of the House Natural Resources Committee held a hearing in July to find out what the federal government could do to expedite development of what Grace F. Napolitano, chairwoman of the subcommittee, characterized as low-hanging fruit. “Small hydropower is not the sole answer to generating enough renewable energy to meet our future needs, but it should be an important part of the solution,” she said in an opening statement. But there are barriers. Permits from the Federal Energy Regulatory Agency, required of any hydro project that delivers electricity into the grid, require specialized attorneys. The return on investment still lags efforts to wring greater efficiency and conservation of existing energy resources. Even so, many smaller hydro projects have been built, and more are coming. A small hydro installation in Cortez had been identified as feasible even 20 years ago. But federal money administered through the Governor’s Energy Office recently tipped the scale. The project harnesses the power of water flowing year round in a canal from McPhee Reservoir to the town’s water-treatment plant. The unit produces 240 kilowatts of electricity, more than enough to operate the water-treatment plant and enough to feed back into the electrical grid. The extra power is sold to Empire Electric.Outside aid was crucial. The city got a grant for $500,000 and also a 20-year loan for $1.4 million at 2 percent interest from the Colorado Water and Power Revolving Fund. Sale of renewable energy credits was the final piece of the financial pie. The plant still produces only a small portion of the City’s annual power production, but the plan will be paid off in 17 to 18 years, with continued production for 100 years. Silverton, too, may get a small hydro plant. There, the San Juan County Historical Society has received $140,000 in grant funding and hopes for another $50,000 to build a generating plant at its Mayflower Mill, located two miles east of Silverton. Even with the low flows of fall and winter, production would more than pay group’s $500 to $600 monthly electrical bills for the historical society’s museum in Silverton. “This is huge for our little old historical society,” says Beverly Rich, the president. “We don’t get any other subsidies or tax moneys.” What Rich really likes about hydropower is that, in her words, it is non-consumptive. “You use the water once, and then it goes back in the river. Talk about green. I think that is the miracle of the whole thing.” In a sense, this is all coming full circle. Among the very first demonstrations of alternating current was in the San Juans Mountains in the 1890s. Water was harnessed at the Ames plant near Ophir and then power was sent over lines 10 miles to the mine. Telluride soon became one of the world’s first towns to have streets lit by electrified lamps. The Tacoma Hydro Plant, located between Silverton and Durango, became the second such plant to produce electricity for long-distance transmission. But in all this, there’s a lingering question. If microhydro is so good, then why aren’t these mountains littered with more small installations? In this, Aspen’s experience may be instructive. Following Telluride’s lead for a change, Aspen installed a run-of-the river (no dam) hydro plant in 1892. The plant at first supplied all of Aspen’s electrical needs, including street lights, but less so in later years as electricity was used for more purposes. Finally, in 1958, the plant was abandoned altogether. Electricity produced by the ever-larger coal plants had become slightly cheaper, and production could be done elsewhere, out of sight and out of mind. In the mid-1990s, to lessen its role in the pollution caused by coal plants, Aspen worked with the U.S. government to install a hydroelectric generating unit in nearby Ruedi Dam. More recently, Aspen has gotten serious about shrinking its responsibility for greenhouse gas emissions. A key component of the strategy is a new hydro plant on Maroon and Castle Creeks, Aspen voters recently authorized a $5.5 million bond for the plant’s construction. Studies and hearings have been underway. If the project doesn’t snag too seriously, Aspen will soon be able to increase its non-carbon portfolio, now at 71 percent, to more than 80 percent. Also contributing to that figure are smaller efforts, such as tiny hydro units in place of pressure-reducing valves. Phil Overeynder, Aspen’s public works director, insists that renewable energy isn’t always expensive. Aspen’s municipal utility has among the lowest residential rates among municipal providers in Colorado. Overeynder – also a part-time resident of the San Juans – advises taking a longer view. “Don’t insist on getting your money back in 20 years. You might have to take a 25-year payback,” he says. Overeynder also urges action now. “I read this time and time again: ‘We can’t afford to do these things.’ But why can’t you? If you had started this 10 to 15 years ago, you could have had these things now – and have low rates. You have to start somewhere.” •

|

In this week's issue...

- May 15, 2025

- End of the trail

Despite tariff pause, Colorado bike company can’t hang on through supply chain chaos

- May 8, 2025

- Shared pain

Dismal trend highlights need to cut usage in Upper Basin, too

- April 24, 2025

- A tale of two bills

Nuclear gets all the hype, but optimizing infrastructure will have bigger impact

Unlike computers, where 10-year-old technology now seems ancient, the technology of small hydro plants has changed little in the last century. Consider the new hydroelectric plant in Ouray. In a shop along the Uncompahgre River, falling water pushes the blades of a generator originally manufactured in 1909. Adjacent to this relic is a linear motor built in 2009 which completes the production of electricity.

Unlike computers, where 10-year-old technology now seems ancient, the technology of small hydro plants has changed little in the last century. Consider the new hydroelectric plant in Ouray. In a shop along the Uncompahgre River, falling water pushes the blades of a generator originally manufactured in 1909. Adjacent to this relic is a linear motor built in 2009 which completes the production of electricity.