|

| ||||

| Dusting off wilderness SideStory: Dust on the horizo

by Will Sands

Dust storms are a natural fixture and have been haunting the Four Corners for centuries. However, when coupled with global warming, dust on snow spells the possibility of big problems for water users. “The science shows that dust on snow is just like putting on a dark-colored shirt on a warm day,” said Terri Martin, SUWA’s Western Regional Organizer. “It increases the energy absorption of the snowpack and causes it to melt faster and earlier.” On the Animas River, early run-off promises to have negative impacts on agriculture and municipal water supplies. In addition, wind and dust increase the sublimation, where moisture simply evaporates, leaving the basin thirsty even after big winters. “Dust is causing the snowpack to start melting up to three or four weeks earlier,” said Ronni Egan, director of Great Old Broads for Wilderness. “That means big implications for irrigators and municipal water supplies as well as ski areas and everyone who is downstream.” Based on size and color of dust particles, researchers know that dust storms originate on the Colorado Plateau, a large swath spanning sections of Utah, Arizona and New Mexico. The cause of the dust, on the other hand, is not so clear.

One man with several explanations is Jason Neff, a biogeochemist with the University of Colorado-Boulder. Neff’s quest for dust has brought him to the San Juans, where he has studied core sediments from several high-altitude lakes in recent years. The samples have enabled Neff to look thousands of years back in time. After analyzing the results, the team has arrived at a conclusion – dust storms are directly tied to human activity. Over Neff’s 5,000-year timeline, the first spike in dust was in the late 1800s, during the first significant settlement of the Southwest. “Prior to settlement, there was not a lot of grazing, roads or soil disturbance,” Neff said. “The soil surfaces were stable, covered with biologic crusts and armored against erosion.” Another spike has hit in recent years, and the size and frequency of dust storms appear to be on the rise again. “In the late 1800s, dust loading skyrocketed and was about five times as high as our background data,” Neff said. “Today, dust is about three or four times the background, and livestock, off-road vehicles, human development, dirt roads and weather are all factors.” Designating wilderness is one way to control these factors, according to SUWA’s Martin. Wilderness automatically precludes off-highway vehicle travel, road building, and oil and gas drilling. Without these kinds of disturbance, SUWA hopes that the frequency of dust storms will drop. “Desert soils that are undisturbed are amazingly resistant to wind erosion,” Martin said. “But when soils are disturbed, even by the passage of a single vehicle, they become much more vulnerable. In fact, one pass by a car damages the soil’s integrity by up to 85 percent.” In this spirit, SUWA and Great Old Broads are throwing cautious support behind a “fast-moving process” to dedicate up to 1.3 million acres of wilderness west of Durango. Utah Sen. Bob Bennett has initiated the process to protect huge swaths of Canyonlands and Cedar Mesa, including spots like Indian Creek, Dark Canyon and Grand Gulch. Bennett hopes to introduce legislation in June and have it adopted as a rider to the Ominbus Appropriations Bill in September. The senator is currently engaging stakeholders in Southeast Utah and asking for input on crafting a wilderness bill for the area. SUWA is excited by the prospect of a Cedar Mesa and Canyonlands wilderness, but remains cautiously optimistic. Because the wilderness bill is on such a fast track, Martin and others will be watching carefully. “We’re excited about the opportunity in the San Juan-Canyonlands region,” she said. “But we want to be sure that whatever comes out of this process will do justice to those amazing landscapes. We’re also concerned about the timeframe, and if it will facilitate quality legislation and a wilderness bill that will survive.” SUWA is the first to admit that wilderness designation will not be a cure-all. However, eliminating dust at the source will be a good first step, according to Martin. “It’s not going to be the overall solution,” she said. “But we need to ask ourselves how we can get behind the steering wheel on the issue, and new wilderness can be a step in that direction.” •

|

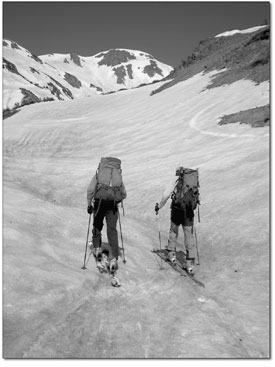

Yet another winter has been dusted in Southwest Colorado. Durango is again weathering dust storms that are accelerating run-off and denuding the region’s snowpack. However, Southeast Utah could be riding to Southwest Colorado’s rescue. The Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance is hoping that designating wilderness in canyon country could help keep future dust storms at bay.

Yet another winter has been dusted in Southwest Colorado. Durango is again weathering dust storms that are accelerating run-off and denuding the region’s snowpack. However, Southeast Utah could be riding to Southwest Colorado’s rescue. The Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance is hoping that designating wilderness in canyon country could help keep future dust storms at bay.