|

| ||

| The customer is sometimes right

by Ari LeVaux

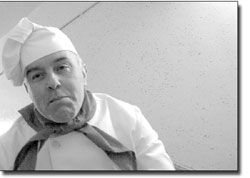

We first heard those words in the antechamber adjacent the dining room of Restaurant Royale Licorne, in Lyons-la-Foret, Normandy. We sipped calvados, a Norman apple brandy, while munching on thin slices of cured ham and petit cheesy puff pastries that evaporated upon contact with saliva. After spending nearly an hour deciphering the menu, we had finally settled upon our choices. The waiter seemed uncomfortable as we ordered, but said nothing. But he quickly returned to the ordering chamber and announced, “I just spoke with the chef.” “All of our food is made to order,” he explained, “and it would be difficult to prepare these dishes at the same time. And the chef says the different textures and flavors of the foods you ordered won’t go well together.” In America we’re used to telling the waiter what we want. Here, it seemed, the waiter was telling us what we wanted. After a few awkward moments of attempting to put together an acceptable order, we finally said “please tell the chef to prepare us whatever he thinks is best.” The waiter was pleased to hear this, and rushed out before we had a chance to change our minds. This meal happened after several days of eating our way around Paris, with the help of a guidebook that was supposed to lead us to some of the city’s best restaurants. The food was generally good, but not mind-expanding. Many of the menus followed a standard set of classic French dishes that relied on butter, crème and fat, and we always had the feeling that the food we wanted was around the next corner – and maybe it was – but we kept squandering our precious gastrointestinal real estate space on dishes that were good, sometimes great, but not educational. All too often, the escargots were muddy, the coq au vin was dry, and there weren’t enough vegetables. But this meal in Normandy was shaping up to be a keeper. The framed, original copy of Napoleon’s will hung on the restaurant wall. And the dining room, decorated in red, grey and charcoal, was adorned with the feathered helmets, hairy hats, uniforms and body armor of Napoleon’s generals. A dusting of barely audible jazz cloaked the silence. The waiter brought bowls of what looked like cappuccino but were in fact snail-stuffed ravioli topped with a foamy lemon emulsion, drizzled with beef reduction, and sprinkled with fruity pieces of cured ham from a rare breed of black Spanish pig, and accompanied with glasses of rose champagne. Next, two-tiered slices of velvety foie gras separated by a delicate layer of smoked hale fish and topped with thin-sliced apples and a thinner sheet of sugar brittle, flanked with a drizzle of balsamic reduction, a small pile of large-grained sea salt, and a bouquet of miniature red and green shiso leaves. Served with a glass of Dernières Grives that was velvety and musky, the foie gras was fatty, silky, sweet, salty, tangy, fruity, fragrant and rich, delivering nearly every flavor the human tongue can perceive. “Normally you only engage 30 percent of the taste buds,” explained the waiter. “We want you to use at least 70 percent.” Each course came with its own chef-picked glass of wine. Every time we told the waiter how good something was, he thanked us. It felt like the waiter, rather than being a servant, was a partner in the shared goal of providing the perfect dining experience. The chef, of course, was the boss, and every time the waiter reported having spoken to him we braced for the update to our plans, which always seemed for the better.The main course consisted of fried pieces of red mullet fish, delicately crispy outside with a moist interior, resting atop a bed of braised fennel. They were sprinkled with crispy bean noodles and drenched in a pumpkin crème sauce. Next, a “pre-dessert” of lemon custard served in a tall glass and topped with almond crème emulsion. And finally, a plate of dacquoise praline with almond and hazelnut meringue and spiced pear. At one point I noticed the chef, Christophe Poirier, peering at us from under the A-framed furry hat of Napoleon’s musketeer. Poirier emerged to applause from the dining room, and we spoke with the chef. Later, the waiter confided that after two years with chef Poirier (the establishment has been open since 1768) the goal is a Michelin star, which has thus far eluded them; a Michelin inspector who visited had not deemed it worthy. One star seemed a humble ambition for such a place, and I had to wonder what fault the inspector had found. Up to three stars are given by the famously stodgy guidebook, which holds such prestige in some circles that one three-star chef, Bernard Loiseau, committed suicide at the mere rumor that he might lose one of his stars. We left satisfied, but not bloated, feeling like we’d spent the evening in the Louvre appreciating art. The meal wasn’t cheap, and for that kind of money it paid to leave the decision in the hands of the guy with a front row seat to the options. In America, we’re used to the customer being always right. But this cowboy didn’t mind having his reins pulled away by a chef who knows best. •

|

"I just spoke with the chef,” we overheard the waiter announce to another party. At our table we exchanged knowing glances.

"I just spoke with the chef,” we overheard the waiter announce to another party. At our table we exchanged knowing glances.