|

| ||||

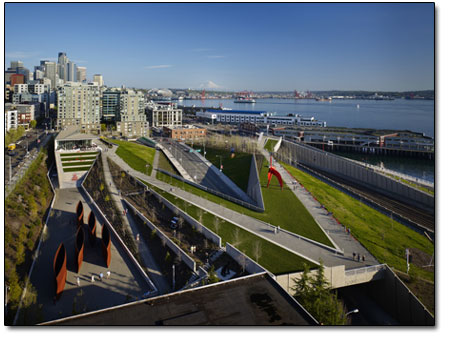

| Olympic caliber art

by Jules Masterjohn Looking out toward the Pacific Ocean, it’s hard to distinguish if the hazy ridge over the watery horizon is the Olympic Peninsula or a bank of moisture. This view from the Olympic Sculpture Park (OSP) in downtown Seattle offers an opportunity to be, as the park’s tagline states, “Where the Earth meets the Art.” The 360-degree view surrounding the undulating, art-filled green space encompasses a dense cityscape of high-rise architecture and the far-reaching vistas of Puget Sound, with the majestic peaks of Mounts Olympus and Rainier beyond. This is a land-locked, rural-living, art-lover’s dream, and it just doesn’t get any better. Opened in January 2007 by the Seattle Museum of Art, the 9-acre urban sculpture park is a spectacular wall-less museum housing some of America’s most celebrated modernist and post-modern sculptors. The permanent outdoor collection currently displays 19 sculptures by 14 artists and offers a rotating schedule of temporary works, all situated in a landscape designed as a work of art itself. A walking path zigzags through the park’s three precincts – The Valley, The Meadow and The Shore – each with its specific microclimate and diverse native species. Once an environmentally contaminated and nearly abandoned sliver of land, the sculpture park sits between the waterfront of Elliott Bay and the city, and is bisected by a four-lane thoroughfare and an active rail line. The park designers, architects Marion Weiss and Michael Manfredi, identified early in their design process that, with such a complex site, “traditional distinctions between art and nature, design and ecology are no longer relevant.” The design was meant to establish connections where separations existed, bringing art to the public and the public to the park, implicitly questioning where art begins and where the park ends. Alexander Calder’s painted steel monumental sculpture, Eagle, greets viewers from the summit of the park and announces itself via its bright orange color. Calder’s stabile is an iconic form and the park’s “mascot,” according to the Seattle Museum of Art. The giant tripod structure is architectural in relation to human scale yet is a mere speck against the backdrop of Seattle’s Space Needle, rising high above and blocks away. Though their scales are vastly different, these two structures share a Modernist aesthetic Three of the dozen entrances to the park showcase a work of art and, one in particular, stopped this viewer in her tracks. Situated at the waterfront walk is a sculptural element common to parks and gardens, but unusual for the nonagenarian artist Louise Bourgeois. Her site-specific work, “Father and Son,” is a pair of classically sculpted male figures – a child and an adult – each encircled by and, on alternating hours, engulfed in vertical shoots of water. It is inspiring to think that even after nearly 70 years of art making, Bourgeois still finds her most compelling themes rooted in her family life. She writes, “My childhood has never lost its magic, it has never lost its mystery, and it has never lost its drama.”

“Father and Son” asks the viewer to consider a closeness among the two, and yet there is a clear separation between them. This is a poignant piece and is quintessentially “Bourgeois” for its provocative emotional quality. This is the park’s only representation of the human form and Bourgeois’ first permanent West Coast work. It is refreshing to see public art that does not have to be watered down and devoid of potent content, like so much of what is placed in the public realm. Three pairs of boulder-sized black granite sculptures situated in the plaza near “Father and Son” are also by Bourgeois. These organically shaped forms, “Eye Benches I, II, & III,” are enigmatic and sensual carved marble sculptures, for which she is better known. On closer inspection, it is clear that they are benches, and though they are hard as rock and can pack a conceptual punch, they are smooth to the touch and pleasingly comfortable on which to sit. Just inside another entrance and sited at the bottom of “The Valley” is Richard Serra’s five-part monumental steel work, “Wake.” Suggestive of the huge hulls of ocean-going vessels, which can be seen just offshore, each module towers 14 feet above the viewer while its 48-foot expanse of rusted, rolled steel confronts one like a slot canyon wall. This is public art at its best, and perhaps, Serra at his best, for “Wake” is able to transport the viewer to a completely different world. For a bit of comic relief, Claes Oldenberg’s colorful and gargantuan “Typewriter Eraser, Scale X,” can be spotted in a dead halt from its trajectory, rolling down a hill into the oncoming traffic of Elliott Avenue. Throughout the park are monumental works by other art world heavyweights the likes of Ellsworth Kelly, Anthony Caro, Louise Nevelson, Beverly Pepper, Mark di Suvero, and Tony Smith as well as works by mid-career artists Roxy Paine, Roy McMakin, Teresita Fernández and Mark Dion. Experiencing the Olympic Sculpture Park is great inspiration for a waterfront sculpture park in Durango. Perhaps our isolated burg could put itself on the nation’s art map by transforming the now dog park, once uranium smelter site, into a sculpture park/peace garden that would greet all as they enter. The views of the park would be fantastic and the landscape’s scale perfect for monumental art. Who knows … it could happen! To learn more about OSP and view all the sculptures, visit www.olympicsculpturepark.org. •

|

In this week's issue...

- May 15, 2025

- End of the trail

Despite tariff pause, Colorado bike company can’t hang on through supply chain chaos

- May 8, 2025

- Shared pain

Dismal trend highlights need to cut usage in Upper Basin, too

- April 24, 2025

- A tale of two bills

Nuclear gets all the hype, but optimizing infrastructure will have bigger impact