|

| ||

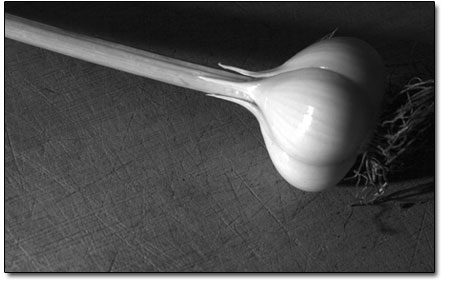

| Garlic as vegetable

by Ari LeVaux Almost everyone loves garlic, but few look forward to garlic season with anything like the anticipation reserved for vine-ripe tomatoes or fresh peaches. The words “new potatoes” on a restaurant menu are often spattered with drool, but new garlic, full of juice, fire and living flavor, rarely makes it into print. This is too bad, because unlike the tired cloves from last year’s crop that languish on shelves and shrivel by the day, new garlic is a fleeting treasure. There’s no bitterness in the new stuff, and no green shoot in the middle of the blinding white cloves, which turn sweet and translucent when cooked whole. After a few weeks the new garlic will cure, at which point it will remain good quality through the winter, but will have lost the luster it had when it was shiny and new. The fresh stuff is usually available only from your garden, farmers market, or high-end green grocer. It’s identifiable by the long, leek-like stalk that’s usually still attached to the bulb and the thick, wet peel that hasn’t yet dried to paper, allowing the cloves to peel as easily as bananas. New garlic is a different animal from its cured cousin, but it can be used in all the ways you’d normally use garlic, with superior results. Additionally, there are ways to use new garlic that take specific advantage of its unique flavor and plump, juicy body. I like to cook it like a vegetable, in whole-clove form. Add cloves to braises and soups, where they float glowing white like massive pearls. Add cloves to a pan with a little oil-try olive oil, safflower oil or bacon grease-and fry them slowly, never letting them surpass golden brown on any one side. After 20 minutes on low heat you can eat them as they are, mash them with steamed new potatoes, scramble them in eggs, or stir-fry them with snap peas, greens, or most any other fresh vegetable and serve with soy or oyster sauce. You can add freshly cooked cloves to anything from rice to a BLT. With the fire cooked out of them, they lend a mellow, sweet and pungent flavor to any dish.Don’t forget the garlic lover’s classic: baked garlic in olive oil. Open a head of new garlic and break it down into its individual cloves, but don’t peel them. Put the cloves in a baking dish or cast-iron skillet with half an inch of olive oil, and bake at 350, stirring occasionally, until the cloves are golden brown and soft-about 25 minutes. Remove from the oven and let cool. Serve the baked cloves with toasted baguette slices or crackers and an assortment of condiments with which to build your own garlic bites. Guacamole, goat cheese, meat, tomatoes, basil and mayo are just a few accoutrements that work well with roasted garlic. Just squeeze the garlic out of its shell and onto the toast, apply condiments, and eat. And don’t forget to save that garlic-infused oil for future use in salad dressing, egg frying, etc. Beyond differences in flavor and performance, there are marketplace differences between fresh and cured garlic this time of year that savvy shoppers should understand. Most garlic sold in stores comes from China, and is usually of the softneck variety, which generally has smaller, irregularly shaped cloves wrapped in paper that shreds into tiny pieces and sticks to your fingers as you try to peel it. Strangely, the market rarely prices a difference between softneck and its superior cousin hardneck, the bigger cloves of which peel much easier and have better flavor. Nor does the market usually distinguish between last year’s shriveled and sprouting bulbs and this year’s young and robust arrivals. Before marketing the fresh stuff, distributors often try to unload the dregs of last year’s crop first. When this year’s crop finally hits the shelf it may have already been cured and not so new anymore. This practice, born of marketing concerns, is widely tolerated only because most shoppers don’t know any better. If the laws of supply and demand weren’t so manipulated by marketers, we’d see deep discounts in the price of last year’s crop. Such bargains are the only scenario in which you should consider loading up on old garlic. And the only thing worth doing with old garlic is a trick I learned in Brazil that goes by the name tempero alho e sal, or garlic and salt seasoning. This paste of garlic and salt is the flavor behind much churrascaria, a style of Brazilian grilled meat that’s becoming increasingly popular north of the border. Rub the paste on the meat, marinate in the fridge for at least an hour, and cook. This simple seasoning also works wonders with soups, beans, veggies and pretty much anything that isn’t for dessert. To make tempero alho e sal, mash garlic and salt together with a mortar and pestle, or use a food processor. I like a teaspoon of salt for every four medium-sized cloves, but it really depends on your own preferred balance of salt to garlic. If you were able to find discounted old garlic, this paste is a convenient storage form that’s ready for use at a moment’s notice – just keep it in a jar in the fridge and bust out a spoonful whenever garlic is called for. Of course, the paste is even better when made with fresh garlic, adding superior pizzazz to whatever it touches. Made with fresh garlic, the bright white slurry, often mixed with olive oil, is an easy sauce for steamed string beans, an unbeatable pre-dressing for fresh pasta, and a valuable addition to reheated leftovers. So put new garlic on your list of things to enjoy before summer slips away. •

|