|

| ||||

| Pueblos to the plains

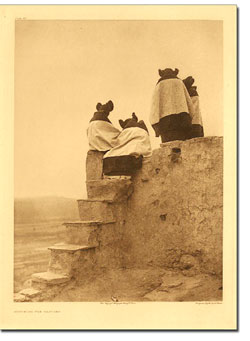

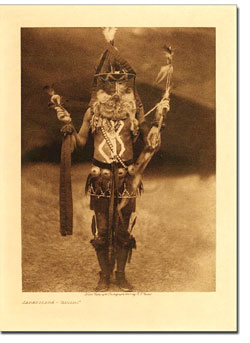

by Jules Masterjohn Once again, Open Shutter Gallery has taken a leading role in bringing significant photography to our region with its current exhibition, “Edward S. Curtis: Images from The North American Indian.” If Curtis’ name doesn’t ring a bell, chances are his images will. He has the distinction of producing the largest portfolio of photographs – more than 2,200 – that document the people and practices of 80 Western Native American tribes. Encouraged by President Teddy Roosevelt, and funded by J.P. Morgan, Curtis began his 30-year documentary project, “The North American Indian,” in 1906. The Open Shutter is presenting more than 60 of Curtis’ images, which have been loaned to the gallery by two private collectors. This is a museum-quality exhibition of original photogravures that should not be missed. Viewing the beautiful, subtlety toned portraits of Native Americans as well as scenes from their daily lives reminded me of the troubling history that determined the footprint of our nation. By the time Curtis began photographing the Western tribes, they had been sought out and subdued for more than 70 years. The end result was relocation and loss of their ancestral lands and spiritual practices, not to mention many lives. The portraits are often poignant when viewed through the historical lens of weariness and loss, which is visible in many faces of the Plains and Northwestern tribes. In spite of this suffering and defeat, expressions of pride, wisdom and determination also can be seen, as in the grouped portraits, “White Shield, Arikara, 1908,” “Double Runner, Piegan, 1900” and “Cayuse Warrior, 1905.” The scenes of daily life within the pueblos of the Southwest have a noticeably different feel than those of the Plains, Plateau and Northwestern tribes. Images such as “Zuni Girls at the River, 1903” “Watching the Dancers, 1906” and “Old Trail at Acoma, 1904,” offer a glimpse into the cultural differences among Native Americans. Perhaps due to the early establishment and continuous habitation of the pueblos, the images taken of them display a strong sense of place. Curtis’ work has been the source of controversy over the years. From a 21st century viewpoint, some find his effort an example of colonization: exploiting the native peoples by “taking” the only thing they had left – their images. (He did pay each person 50 cents to be photographed, today’s equivalent of roughly $12.) Some accuse him of romanticizing the Native Americans, depicting them as “noble” and “primitive.” Others find fault in his documentary process: he was known to occasionally ask his sitters to put on ceremonial clothing and adornments for their portraits, and he sometimes carefully arranged artifacts around them. While Curtis was influenced by the historical and cultural perspectives of his time, he felt that he was documenting a “vanishing race,” and his writings indicate that he valued and respected the Native Americans and their practices.

While the ethnographic contribution of Curtis’ photography is readily acknowledged (though sometimes questioned) it often overshadows the works’ artistic merit. Curtis, the artist, was able to portray each sitter’s character, producing emotionally provocative and moving portraits. Revealing the sitter’s inner life is the hallmark of a great portraiture artist. Kirk Rudy is one of the exhibit lenders and a Curtis connoisseur. According to him, Curtis has been compared to today’s premier portraitist and fine art photographer, the late Richard Avedon. Not only was Curtis a consummate photographer, but also an innovative filmmaker. In the film, “Land of the War Canoes,” made by Curtis and released in 1914, he utilized a panning technique that wasn’t adopted in Hollywood until 1928. Rudy believes that Curtis was sincere in his effort to honor and memorialize the indigenous peoples and their cultural practices. He also stresses Curtis’ commitment to The North American Indian project and his willingness to accept the challenges that a project of this magnitude would present. One daunting fact was Curtis’ technical process: his photogravures were produced using a sophisticated process that utilized a large format camera and glass plate negatives, which were transferred onto copper plates and finally, printed on paper using an intaglio process. Curtis literally carted around 14-by-17-inch glass plates on which to capture his images. Rudy tells of Curtis losing a wagon at the White River in Arizona, and remarking in his writings that one could not allow the “obstacles to cloud the importance of the work.” Rudy states, “Here is an individual who we can look up to for his dedication and perseverance. To complete that project must have been an immense amount of effort. During winters, he would lock himself away writing over 250 pages of text to accompany each of the 20 volumes of photogravures.” Paraphrasing Curtis’ words, Rudy emphasizes the photographer’s goal with The North American Indian project, “I have captured the past for the present to be used for the future.” • “Edward S. Curtis: Images from The North American Indian” will be on display at Open Shutter Gallery, 735 Main Ave., through April 14.

|

In this week's issue...

- May 15, 2025

- End of the trail

Despite tariff pause, Colorado bike company can’t hang on through supply chain chaos

- May 8, 2025

- Shared pain

Dismal trend highlights need to cut usage in Upper Basin, too

- April 24, 2025

- A tale of two bills

Nuclear gets all the hype, but optimizing infrastructure will have bigger impact