| ||||

The new gold rush

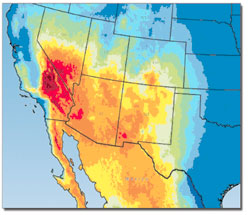

by Allen Best Boy, are we ever in an energy pickle. Just how much of a predicament was made clear recetly by Daniel Nocera, a researcher of renewable energy at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In a lecture at Telluride’s Moving Mountains Symposium, Nocera laid out some hard facts: About 3.2 billion of the planet’s current 6.2 billion people have energy-intensive lives. Add an additional 3 billion people – and assume everybody uses lots of energy, like we do now – and we’re talking a tripling of energy demand by mid-century. Where in the world can we get it? We can, of course, use energy more efficiently. Electric cars, for example, are six times more efficient in energy use than gas-fired internal combustion engines. Or perhaps we can figure out how to decarbonizes our coal deposits. Renewables also are certainly an option, but as Nocera made clear, the knives in this drawer are not of equal sharpness. Consider biomass. If every last blade of grass on Earth were converted into energy, it would still be insufficient to feed our voracious appetite for power. Wind is only a partial answer. Most promising is solar, he said, even if new technology is needed to make conversion to electricity more efficient and provide for longer storage (photovoltaic panels are only 22 percent efficient and are limited to six hours of life in industrial applications.) If this happens, the sky is the limit. But even without it, a new rush – this time for golden rays of sun – is on in the American Southwest. Forget about Colorado’s generic boast of 300 days of sunshine per year. That includes days when the sun appears only briefly. In maps of solar potential issued by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, much of Colorado’s complexion is a bit on the pale side. Really good solar is represented on the map by deep red, tending toward purple. Think of road rash. Parts of the San Luis Valley look like that, and the broad swath of desert from St. George, Utah, to the outskirts of Los Angeles, Calif., looks like flesh rubbed raw on asphalt. A trio of scientists, writing in the Dec. 16, 2007, issue of Scientific American gushed about what they called the “solar grand plan” that could, they say, end U.S. dependence on foreign oil and slash greenhouse gas emissions by mid-century. Only 2.5 percent of the radiation falling in the Southwest could, if converted into electricity, match the nation’s total energy consumption in 2006, said Ken Zweibel, James Mason and Vasilis Fthenakis. The scientists estimated that 250,000 square miles of land in the Southwest are suitable for solar power plants. But there are differing opinions about just how much of this land – especially that in the public domain – should be dedicated to solar resources. The sharpness of that disagreement became evident in June, after the federal government’s Bureau of Land Management ordered a moratorium on new solar applications. Since late 2006, the BLM has been flooded with 130 proposals to use public land for solar installations, about half of them in California’s San Bernardino County. The nation’s largest county, it stretches from the suburbs of Los Angeles to the Nevada border, nearly to Las Vegas. But as big as the desert is, there are competing needs and uses, pointed out Brad Mitzelfelt, a San Bernardino County supervisor. “All we are asking is that we slow down to make sure these projects don’t do irreparable harm to our shrinking desert,” he said. Andrew Silva, an aide to Mitzelfelt, further explained that San Bernardino County already has the Mojave National Preserve and parts of Joshua Tree and Death Valley national parks, plus two military bases that hope to expand. Wind farms are also proposed.

“The Southwest is not a big, flat, empty parking lot,” added Silva. “It is a thriving, sensitive, fragile ecosystem.” The BLM lifted the moratorium in early July, responding to unhappy solar companies and public officials. “Time is not on our side,” said Morey Wolfson, of the Colorado Governor’s Energy Office, criticizing the moratorium. If anything, climate change dictates a ramped-up development of renewables, he said. “We can’t push this off for 10, 20 or 30 years.” U.S. Rep. Mark Udall, D-Colo., who is running for the U.S. Senate, was among those protesting the moratorium, but far more important was the voice of Nevada’s Harry Reid, the Senate majority leader. The moratorium, he said, “is the wrong signal to send to solar power developers, and to Nevadans and Westerners who need and want clean, affordable, sun-powered electricity.” Still continuing is work on an environmental impact statement that would provide a broad, consistent policy governing installation of solar collectors on the 119 million acres of BLM land in six Southwestern states. That overview is expected to be complete in 2010. Meanwhile, California’s mandate for renewable energy is fueling a solar gold rush.The state requires investor-owned utilities to get 20 percent of electricity from renewable sources by 2010. As of last year, they were at 13 percent. Now under discussion is a new goal of 33 percent by 2020. As such, the rush into the Mojave is creating ironic partnerships among traditional adversaries in public land disputes. “You have folks who have been at war for decades who are saying: ‘Wait a minute,’” reports Silva. “You have the OHVers and Sierra Clubbers on kind of the same page.” Off-highway vehicle enthusiasts fear loss of access to public lands. Environmental concerns are focused on habitat for the desert tortoise, which is listed as threatened in the Mojave Desert under the nation’s Endangered Species Act. Solar plants require large areas, says Silva. A few acres dedicated to burning natural gas can produce as much electricity as a solar farm requiring hundreds of acres. “Until the technology changes, and they can put the solar collectors into the rocks and cliffs, it will impact desert tortoise,” said Greg Miller, renewable energy program manager in the BLM’s California Desert District. “That will be a huge issue itself, determining how much impact we can tolerate to these desert species.” The Wilderness Society urges development – but with caution. “We need energy, but we also need healthy lands,” said Alex Daue, a Denver-based outreach coordinator for The Wilderness Society. Daue cautioned that the furious pace of oil-and-gas drilling under way on public lands in the Rocky Mountains should not be repeated in the rush to harness the sun. Craig Cox, executive director of the Interwest Energy Alliance, sees it from a different angle. “You are talking about hundreds and thousands of drilling pads in Wyoming and Colorado and elsewhere. We are talking about dozens of solar projects at most that I expect to see at the end of this process.” Cox welcomed the moratorium’s demise but also continuation of the EIS review. “Solar utilities need certainty. Wind developers, coal, nuclear – you name it, they all want certainty in their planning and regulatory process, and at the end of the day, I think the EIS process will provide even greater certainty.” But Cox this week also rued the absence of a green light for solar. “We need to get the BLM to start approving projects,” he said. Taking the big picture of this latest dustup in the desert is Auden Schendler, the vice president for environmental and corporate responsibility for the Aspen Skiing Co. What is happening now is the “growing understanding of the scale of the problem,” he said. That problem is so large, Schendler added, that “we will have to make compromises like putting wind turbines in beautiful places.” Just how much room will be left for desert tortoises remains to be seen. •

|