|

| ||||

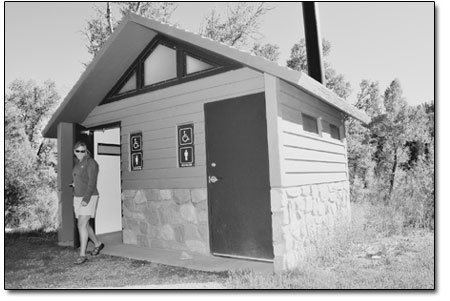

| The Kybo keeper

by Michelle Duregger As you reluctantly press your cheeks to the latrine pedestal after a sweaty hike on Molas Pass, ponder this: From the La Plata Mountains to Lemon Reservoir, one brave soul has been tending these Kybos for 21 years. In that time, Michael Rash managed to squirrel away enough cash to retire from his latrine-cleaning career. His story is not glamorous, nor that of a trustafarian. His is the story of being in the right place at the right time with few expectations. “I just clean them. How long they stay clean is the question,” says Michael Rash, as his dark eyes squint in a smile behind perfectly circular spectacles. The 65-year-old Forest Service sanitary technician, as was his official title, is currently on sick leave with plans to pass on the torch and retire next month. Each spring since 1982, Rash’s seasonal work has begun with a fresh flush. “What I’ve simply done for all these many years … is clean shitters,” he explains. Early every morning for the last two decades, Rash and Froggy (his green service truck) set out from the Trimble Work Center to grind out 150 miles a day. “Me and the guys (Froggy and, later, his next truck, the Green Hornet) would drive and fight with the ‘pilgrims’ – campers and hikers – when necessary.” Rash’s route ran a circuit hitting each of the 21 “dispersed units” around the Columbine Ranger District. The hikers, fondly dubbed “pilgrims,” were one of the nastiest challenges to the job. “I didn’t cater this thing to be that the customer is always right, because they’re not,” says Rash, “I wasn’t taking any bullshit – that kind of made it fun from time to time.” Despite the dirty nature of the job, it was a good fit. In 1982, Biff Stransky contacted Michael while he and his wife, Maggie, were campground hosts near Purgatory. Stransky brought down an application and soon Rash was working to maintain the “honey buckets” at campgrounds and those dispersed around the old Animas Ranger District. The job was laid back: Rash worked alone, at his own pace, with the opportunity to picnic everyday in serene forestland. Tending the loos offered job security as well, “Nobody messes with the doo doo guy,” says Rash. Though very few critters stopped to use his restrooms, each morning brought opportunities to for wildlife viewing. Bear and deer as well as porcupines and other animals roamed about in their natural habitat and brightened the job ahead for Rash. Not only was he able to be in pristine forest daily, but he was also privileged to work with highly conscious rangers who were genuinely concerned about the environment. Tending the latrines also proved comical, if not hazardous, from time to time. Rash recounts the tale of a Clevis Composting Toilet once resided near Kennebec Pass in the La Platas. “Ecologically, it was a neat design,” admits Rash. Unfortunately the eco-crapper failed miserably at high altitude, and the road up to the Clevis was rough and slow going. The job was to rake and turn the uncomposted, mulchy mess to help the process along. As Rash climbed into the pit below the restroom and dug into the nasty job, he heard ominous footsteps in the gravel above. The doors were propped open to alert hikers that there was latrine maintenance in the works, but it wasn’t a foolproof measure. “I thought to myself, ‘You know, someone’s going to go in there,’” says Rash. Sure enough, the door slammed shut behind a woman. After a few tense moments, a stream began to rain down from the portal above. “I began banging the chute with my rake handle and yelled, ‘Goddamnit, I’ve got my head in this down here, and I’m working.’” Mid-story, Rash chuckles, clenching his fist, “I’ve never seen anyone cut off their peeing job so quick.” The startled hiker ran out, hailing her hiking party with, “We’ve got to get out of here! We’ve got to get out of here now.”

In addition to these kinds of encounters, each day held side adventures after the unit was cleaned. Rash says he took frequent hikes to Hermosa Lake, Henderson Lake and any other location he fancied. It all fit his wandering lifestyle. “It made it all worthwhile,” he says. Rash first wandered into Durango in 1974 after working for Marriott Hotels in Texas. After eight years in the corporate world in upper-level management, he had decided to escape. He soon found himself working for a condominium complex, where he met his wife, Maggie. The next year Rash found seasonal work at Tamarron. Working maintenance at the resort until a back injury in 1982, he stumbled upon the Forest Service sanitation job. During winter months, Rash took up waiting tables at Tamarron, a job he held for 27 years during the latrine-cleaning off-season. With constant joking and crazy antics, Rash and his fellow seasonal workers made waiting tables a “show biz” affair. “Sling that hash, talk that trash, make some cash, smoke that grass … We made people laugh,” explains Rash. He and his fellow resort workers stuck together for more than 10 years waiting tables and stirring up trouble together, he says. These two worlds of seasonal work were refreshing for Rash. In between jobs, he sandwiched four to five weeks of rest and relaxation, hanging out with Maggie. Five years ago, Tamarron was bought out by the Glacier Club and Rash began taking his winters off. After a bit more wandering in Florida and Pennsylvania, Michael and Maggie returned to Durango in 1992. His old job with the Forest Service Sanitation Department was taken, so he worked in law enforcement until the sanitation job opened up again. The sanitation job opened back up at the end of the season, but in an unfortunate way. The worker that had taken his job in his absence took his own life. “Many people think that I got a cushy job, that’s not true,” Rash says. “It drove him so crazy he committed suicide at the end of the season. I didn’t want to get it back that way, but that’s what happened.” As the years wore on, nearly two decades of dealing with disrespectful pilgrims began to wear on Rash. “I found myself thinking, ‘I’m gonna choke one of these sons of bitches pretty soon, so I better quit.’” It wasn’t that all pilgrims were rotten, Rash adds. There were many wonderful people, but the bad apples soured the job. Before encounters with heckling hikers got physical and in the face of health problems, he thought it best to retire in October. “I will be happy, come October, if I never clean another toilet again,” Rash says with a grin. And as that magic date approaches, the outgoing Kybo keeper has some advice for the Columbine Ranger District’s new sanitation workers: “Wear gloves and don’t be squeamish. You’re going to see a little bit of everything.” •

|

In this week's issue...

- May 15, 2025

- End of the trail

Despite tariff pause, Colorado bike company can’t hang on through supply chain chaos

- May 8, 2025

- Shared pain

Dismal trend highlights need to cut usage in Upper Basin, too

- April 24, 2025

- A tale of two bills

Nuclear gets all the hype, but optimizing infrastructure will have bigger impact