| ||

Crouching tiger, hidden drum

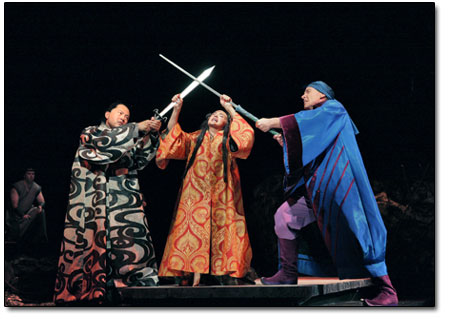

by Judith Reynolds Santa Fe Opera rarely disappoints. With its multimillion dollar budget, how could it? John Pennington’s percussion concerts are more the shoestring variety, but they, too, have never been less than surprising. Last Sunday’s recital in Roshong Recital Hall was no exception. Professor of percussion studies at Fort Lewis College, Pennington always manages a page turn in the story of new music. This time it came packaged with his colleague and friend, the superb trumpet player Stephen Dunn. Formerly a member of the FLC music faculty, Dunn now teaches at Northern Arizona University. The two have formed the Dunn/Pennington Duo, and this recital featured all new music or new arrangements of old music. For example, the men took a fresh look at Bach, Vivaldi and Ravel. As an added fillip, Dunn invited FLC trumpet professor Tim Farrell to join him in a two-minute chase by Anthony Plog that disappeared almost before it began. Only last month, the Santa Fe opera mounted a new work by Tan Dun, a Chinese-born composer most famous for his film scores including “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon.” While much larger in scope, the opera, “Tea: A Mirror of Soul,” had one thing in common with the recital: Both presented fresh, bold, edge-of-the-seat contemporary music. Pennington/Dunn and Tan Dun may be worlds apart, but they share an openness to the idea of blending unusual musical sounds and textures, and freely mixing Eastern and Western traditions. Sunday’s recital mesmerized a local audience with an astonishing collection of pieces that ranged from “Awakening,” a fierce, modern fanfare by David Crumb, to a poignant transcription of tangos by Astor Piazzola. Pennington and Dunn are musician/composers who have a flair for finding new sororities in the many instruments they play. No fewer than five different trumpets lay at Dunn’s feet with five mutes to the side. He also played the tambura, a South Indian drone in the lute family, plus the glockenspiel. Pennington moved like a light-footed giant among his forest of percussion instruments: marimba, vibraphone, chimes, gong, Caxixi (a Brazilian basket of seeds), Bodhran, snare and bongo drums, plus an exotic, table-top instrument full of wooden blocks and metal domes. It had the same configuration as a keyboard, Pennington said, but not the same pitch references. “Glass Façade” was Pennington’s most innovative composition. Inspired by the lyrical French surrealist Paul Klee, the work found the two musicians sitting in chairs side by side. Pennington alternately played two instruments, a small drum and an even smaller kalimba, or thumb piano. In what looked like a new invention, a double rank of tiny metal tongs, Pennington produced a rapid, polyphonic soundscape suggesting glass shards sparkling in the sun. Meanwhile, Dunn gave the piece a steady undertone on the tambura and soft bell sounds on the glockenspiel, both instruments remarkably balanced on his knees. Dunn’s spectacular new work, “The Electric Flugelhorn” introduced what he called his “electronic toys.” The work combined a loop station and digital delays that made Dunn’s live, smoky playing reverberate as if he had a full brass choir hidden in a resonant tunnel. Pennington underscored the melodic lines with sprightly taps, scratches and sighs on the Bodhran, his Irish-frame drum. This haunting piece with its shifts and surprises is what I mean by edge-of-the-seat, new music. The same “what next” feeling suffused the Santa Fe Opera’s American premiere of “Tea: A Mirror of Soul.” When it opened last month, a solitary onstage musician scooped water out of a huge glass bowl and let it drip back. Illuminated from below, the black-clad musician stood in a huge Plexiglas box. Amplification heightened the sounds of the water, and the effect seemed at once strange and familiar. As the ritual of scooping and poring continued, low strings in the orchestra gradually entered, hovering below as if from a dark underground chamber. You knew you were in for a new operatic experience. Tan Dun is known more for his groundbreaking film scores than for his numerous operas. If you’ve seen “Crouching Tiger,” you already have an idea of his tantalizing East-West vocabulary. But he’s also composed a series of operas, including “Marco Polo” in 1996, followed by “Peony Pavilion” in 1998, and last year’s “The First Emperor,” which brought a new soundscape to the Metropolitan Opera in New York. Before he left China for the United States, Tan Dun led the controversial New Wave of Asian composers. He continues to incorporate sounds from multiple sources – different cultures, styles and time periods. He also includes organic instruments to capture the earth’s natural music: rushing water, chattering stones, wind in trees. Tan Dun is not alone in this expansion of the sonic landscape. It’s a worldwide phenomenon. If you’ve been to any of Pennington’s concerts, you know he’s been known to play tuned rice bowls, strike clay pots or suspend oxygen tanks on tracks as if they were sacred temple bells. In the universe of “world music,” this kind of experimentation has been going on for some time. In “Tea: A Mirror of Soul,” Tan Dun and his co-librettist Xu Ying began with a simple, ancient story of a love triangle. It’s the stuff many Western operas are made of: Two rivals fight over a woman they both love and the sacred Book of Tea both wish to possess. The composer wrapped this basic tragedy in a magnificent web of musical motifs interspersed with natural sounds. Using water, fire, paper, ceramic and stones as thematic markers for each section, Tan Dun also introduced musicians “playing” water and shaking huge paper streamers that sounded like distant thunder. At one point, even orchestra musicians rustled their scores to create a wind-swept whisper. Chorus members slowly tore paper as the opera approached its climax then clattered stones together in a tumult of sound when death and regret completed the story. I’m not even mentioning the spectacular sets or costumes; this review is about the music. Serious music of our time often carries a charge unlike any other. Whether in a small recital hall or the stage of a multimillion dollar opera company, new music can deliver the tart taste of our own era. Music may not end war, but it just might be one path for civilization out of the darkness. •

|

In this week's issue...

- May 15, 2025

- End of the trail

Despite tariff pause, Colorado bike company can’t hang on through supply chain chaos

- May 8, 2025

- Shared pain

Dismal trend highlights need to cut usage in Upper Basin, too

- April 24, 2025

- A tale of two bills

Nuclear gets all the hype, but optimizing infrastructure will have bigger impact