|

| ||||

| Bearing witness

by Jules Masterjohn

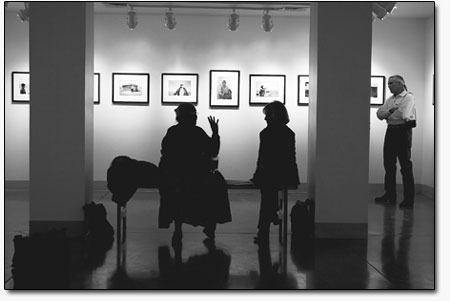

Santa Fe-based photographer Carlan Tapp follows in this tradition, turning his lens toward a situation close to home but of global importance. His exhibit “Question of Power,” currently on display at the Fort Lewis College Fine Art Gallery, is a photographic documentation of the Diné (Navajo) people’s struggle against corporate and tribal powers and the proposed Desert Rock power plant and its associated strip mine on the Navajo Reservation near Shiprock.

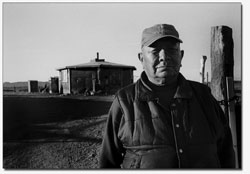

A number of the black and white photographs in the exhibit show the stark and quiet beauty of an arid desert environment, a landscape that is home to cultural and spiritual sites that are of significance to the Diné people. Sacred mountains, burial sites and places that have been inhabited for generations by the same families, are pictured. A large number of photographs are portraits of the people themselves, who will live in the shadow of the proposed power facility. When Tapp first decided to make the Diné people the subject of his inquiry, his intention was to tell the story of their illnesses, in particular, their lung ailments, related to living in close proximity to two existing coal-burning power plants and strip mining activities. What he ended up with is a pictorial document that he hopes will educate people about the “costs of turning on a light.” “When I start a project, I just start it,” Tapp explained. “As I spent more time there, I saw so much sickness and the tribal leadership just shrug it off. They say, ‘Oh, it’s the people’s diets’ or that they don’t exercise. Well, it’s just not true. When I spend a night there, I have to cough yellow crap out of my throat the next morning before I can begin my work. My goal is to be the ‘witness,’ to show the truth.” Tapp said the camera is a powerful tool in developing the ability to “see.” “When a photograph works, it is because the photographer has eliminated the camera and is sharing a piece of his or her personal feeling with the viewer,” he said. “The camera’s strongest point is its authenticity … the appearance of the world. Events can be changed when people begin to see.” Lucy A. Willey, whose family has lived on the Diné reservation for three generations, said she4 believes that Tapp’s photographs will help her people’s voice be heard. Willey recalled when the Four Corners Power Plant was built in 1960 on the reservation. “We didn’t stop it because we didn’t know what was going on,” she said. “They said we would get running water and electricity because the power plant would make us money. We didn’t know any better back then. We never got the water. It was an empty promise. And now our cows and sheep are dying, and people are sick. Now we know better and we say, ‘Dooda Desert Rock.’” Translated into English, “dooda” means “no” in Navajo, and it is the rallying call for the Desert Rock resistance. Willey said their cause is being supported by Native Americans across the country. “A tribe from California called me the other day and told me that they were having a prayer ceremony for us.” Willey’s is one of the portraits that hang on Tapp’s studio wall, along with those of medicine man, Jim Mason, and 89-year-old Louise BeNally. “I look at them, and it reminds me that there is more work to be done,” Tapp stated determinedly. Tapp’s strong sense of social justice is in his blood. He is part Native American and he can trace his lineage to a distant great-grandfather who “butted heads” with Captain John Smith in the Virginia colonies. “The only reason we know this, is that when my great grandfather complained about his treatment, the authorities told him to make a formal complaint,” he said. That complaint was filed in a court document dating from the early 1600s. Early in his career, Tapp was influenced by the work of W. Eugene Smith, a war correspondent whose conscience was aroused while photographing the Japanese victims of World War II. Smith later documented the birth defects from mercury poisoning among residents in a Japanese fishing village caused by industrial pollution. Inspired by Smith and other photojournalists, like Gordon Parks and most recently, James Natchwey’s hauntingly quiet images of Ground Zero, Tapp has committed himself to “telling stories” with his camera. “I have always felt strongly for the principle of human rights,” he said. “As I have experienced more things, seen more, learned more, photographed more, I have begun to fully understand how the camera can be a very strong statement for social justice issues.” Tapp’s next project is titled “Fueling America” and will document the true social cost of “fuel” in the United States today. “I have been given the opportunity and gift of being a photographer. With this comes the responsibility to use it wisely. If my photographs can raise awareness and help people to obtain their rights, part of that responsibility may be accomplished.” Tapp has not only used his photographs to raise awareness, he has created a nonprofit organization, also named Question of Power, through the New Mexico Community Foundation. All proceeds from the sales of photographs in the exhibit will benefit the Dooda Desert Rock effort. • “Question of Power” is on display at the Fort Lewis College Fine Art Gallery through Nov. 29. Gallery hours are Mon. –Fri., 10 a.m.-5 p.m. For more information about “Question of Power” or the work of Carlan Tapp, visit the websites www.questionofpower.org and www.carlantapp.com.

|

A person can write the best story in the world, but a photograph is absolute,” said Eddie Adams, the photojournalist who won a Pulitzer Prize for his now-famous image of the execution of a Viet Cong prisoner by a South Vietnamese soldier in Saigon during the Tet Offensive of 1968. Adams understood – intimately – the power of the camera, held by conscious hands and courageously directed toward a hard truth. Since the invention of the camera, many of the best photojournalists have embodied these qualities and have returned from places near and far, with pictures that document what most of us couldn’t bear to see with our own eyes.

A person can write the best story in the world, but a photograph is absolute,” said Eddie Adams, the photojournalist who won a Pulitzer Prize for his now-famous image of the execution of a Viet Cong prisoner by a South Vietnamese soldier in Saigon during the Tet Offensive of 1968. Adams understood – intimately – the power of the camera, held by conscious hands and courageously directed toward a hard truth. Since the invention of the camera, many of the best photojournalists have embodied these qualities and have returned from places near and far, with pictures that document what most of us couldn’t bear to see with our own eyes.