| ||||

Sympathetic magic

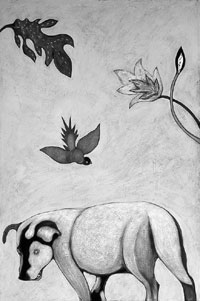

by Jules Masterjohn As an exercise of our innate creativity, humans have been making images since 30,000 BCE. Appearing on rock walls in caves on nearly every continent are paintings created by early humans. Most predominantly pictured are animals, both herds and individuals, with an occasional human present. Theories about who these makers were and the drawings’ intended purposes are plentiful. One hypothesis is that the creators were shamans or healers, and their role within a clan or tribe was to assist with the survival of the social group. One theory about the maker’s motivation was to picture or visualize the positive future outcome for a hunt, a concept termed “.” This line of thinking goes that, to the prehistoric mind, if one could reproduce the likeness of an animal or many of them together, one could “vision” this picture into existence. Envisioning, then drawing herds of deer on cave walls, for example, would have been a practice in manifesting abundance. More deer meant more potential food, which led to greater chances for human survival. If this theory is accurate, our race’s survival and proliferation can be credited to our ancestors’ dedication to creative visualization. Local artist Phyllis Stapler employs a similar motivation in the creation of her mixed-media paintings. Unlike these early creators, she is not reproducing an animal’s likeness to capture it for her survival needs but rather for the animal’s right to exist. Stapler, a long time animal lover and a vegetarian for 20 years, is sympathetic to the plight of all animals living in a world dominated by human activity. As an act of preservation, Stapler places each animal within the protection of her canvases, proclaiming it a safety zone. Whether domestic, endangered or rare, animals are compelling to her. Feral cats, missing dogs, Tasmanian tigers and jackals are her beloved subjects. “I can’t shield myself from animal pain, so I create a narrative in my paintings to make it all right. I add a beautiful flower and a bird friend, then, in that moment, everything can be safe for that animal,” Stapler offers. The Madagascar fossa, an odd hybrid creature related to the mongoose that flies like a squirrel, has a special place in her heart. Possessing both canine and feline characteristics, it fits comfortably into either world. The fossa is perhaps an apt symbol for an artist’s identity: a being whose mind lives in imagination and possibility and whose body is grounded in the physical act of art making.

Stapler makes paintings whose compositions are simple and reflect her interest in the early minimalist artists from the Bauhaus school, where “less is more” was professed. Placed within each canvas lives a mammal, a bird and some foliage. There is no sense of deep space, no place that can be deciphered. Stapler utilizes a modern sense of space where depth is flattened and all the visual elements lie in the foreground. “I don’t want to use a horizon line or make any reference to a traditional portrayal of space,” she told me, “I want to keep where the animals are located ambivalent.” By keeping the animals’ location uncertain, Stapler reinforces the metaphoric protection for her four-legged friends. In her painting, “Blind Dog,” the main protagonist is a white-eyed dog who stands in the center of the canvas, looking at the viewer with a toothy grin. Two stylized plant forms offer this animal a friendly canopy and a lovebird hovers overhead. Stapler introduced the bird into her compositions some years ago to symbolize freedom. Her early exposure to art can be credited to a few eccentric family members. “We had my cousin Dot’s florals in our house when I was growing up. She made a meager living as an artist, and I was always cautioned not to end up like her. Another cousin, Frank, showed me a painting he’d done in high school. I was only 5, but I’ve never forgotten the image of a purple cube on fire, floating above a cat in a landscape. He swears to this day he doesn’t know what I’m talking about when I bring it up, but it’s emblazoned in my memory.” These artistic role models coupled with her deep desire to live a life filled with possibility, led Stapler to study art, despite her parents’ warnings. She earned her bachelor of fine arts with an emphasis in drawing and painting from the University of Georgia in Atlanta. She went on to study film animation and took circus arts classes where she flew like a bird on the trapeze. Today, she has sworn off flying, preferring to leave that to the winged things in her paintings, and she juggles colors instead. Stapler’s identification with the animal world may come from her understanding of the vulnerable nature of being an artist in our culture. She has nurtured and protected her own creativity over the last 30 years, making art her profession, a commitment that has required her to waitress, bartend, teach and work in art galleries, to make ends meet. She has found success with her paintings of late and is now working in her studio full time, for being an artist is the “only line of work that makes sense to me.” • Stapler’s paintings are on display at Ellis Crane Gallery, 934 Main Ave. Gallery hours: Mon.-Sat. 10 a.m.-6 p.m.

|