|

| ||

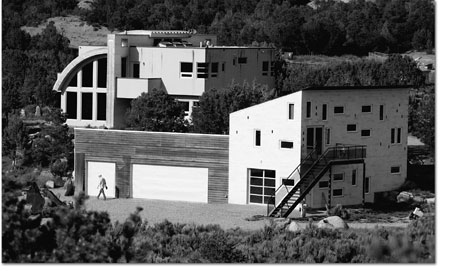

| Adventures in architecture

by Jules Masterjohn Creative thinkers, more often than most, wander beyond the boundaries of the mainstream and test conventional assumptions. Durango-based designer and artist Jeff Madeen has crossed into territory that is a bit foreign to the conventions found in rural areas like ours. His “techno-primitive” design style, however, is finding a place in our geographically isolated corner of the world. Madeen and business partner, Matthew Clark, with numerous projects on their electronic drawing boards – large screen computers equipped with high-powered design software – are busy bringing contemporary architecture to neighborhoods near you. Having recently completed the building that houses his “dream studio,” the office for his business, Kitchens By Design, and the headquarters for his and Clark’s enterprise, Analog Architecture + Design, Madeen is feeling at home in his 2,700-square-foot modernist structure. Located on the same site with a home he also designed, the addition of the studio/office/garage building completes what feels like a creative compound – a duo of buildings that reminds us architecture is meant to be art. These structures reinforce the notion that buildings can be large-scale sculpture that we move within and that provoke us emotionally and intellectually. The structure, heated by a geothermal heat pump, today’s most energy efficient technology, also fulfills Madeen’s ethics of using sustainable materials and processes. Words that come to his mind when asked how he wants people to feel inside his space: “Engaged, interested, inspired and alive.” Intrinsic to his design philosophy is dichotomy, the celebration of dualistic concepts like rough/smooth, natural/machined, hard/soft and new/old, to name just a few. Within this idea, the design must look simple but may be involved and complex. Living in a contemporary structure is nothing new to Madeen. In the early 1960s in Elgin, Ill., his family resided in a modern dwelling that was an oddity amidst the typical ranch and split-level style homes surrounding it. His father, a graphic designer, had forward-thinking tastes and hired a former student of master architect Mies van der Rohe to design the home. Consequently, Madeen grew up living in “a contemporary box with clean design and great windows that opened to the wooded areas outside.” Though the home didn’t fit the neighborhood, it fit the modernist aesthetics of his father, who attended the American Academy of Art in Chicago. “My dad was a really creative guy,” Madeen told me at his new workspace last week. Looking around the inside of the office, I believe Madeen inherited a healthy dose of his father’s avant-garde spirit. My eyes moved from one surface and texture to another on a journey of discovery, like following the lines of electrical conduit that connect receptacles, outlets and switches to the block wall. This “revealing” is part of Madeen’s concept. “Don’t hide it, show it. I like to express the connections between materials.” This is well illustrated where the shiny, chromed fasteners hold the rusted corrugated steel panels to a partition wall inside the studio. The block walls show evidence of their construction. Certain areas, where the masons smoothed mortar over the blocks, reveal an irregular visual quality in contrast to the regularity of the E-Crete blocks used to build the structure. The hard-edged, two-story structure is softened by the fleshy pinkish hue indigenous to the block and mortar. Madeen developed his aesthetic philosophy while attending the Art Institute of Chicago. During that time he also practiced carpentry and worked for designers, where he was exposed to numerous ideas, and new materials and processes. Ever curious and constantly refining his own design sensibility, he remembers, “I was apprenticed to many designers who had no clue that I was studying them.” Anxious to get out in the world and practice his design skills, he quit attending the Art Institute, shy one art history class to earn his B.A. in fine art. It must have been in his other art history classes where he gleaned the lessons from 20th century architects, those modern masters that have informed his own aesthetic. Gazing at the studio’s south wall from the outside, I can see the influence of the world-famous architect Le Corbusier and his chapel in France, Notre Dame du Haut, with its massive wall interrupted by many various shaped windows. As with Le Corbusier’s building, the windows in Madeen’s south wall visually lighten the two-story high wall and literally bring light into the interior. In addition, small, colored, glass panes are distributed throughout the wall, allowing colored light to playfully project inside, slowly moving across the workspace on a late spring afternoon. “Light is the most important element to my designs because it’s ever changing,” offers the designer/artist, “plus it’s free.” Materials are of special interest to Madeen, and low cost or “low brow” materials are often part of his visual vocabulary. Inside his workspace, concrete can be found as countertops, cabinet-grade plywood as window trim, and corrugated metal panels as ceiling covering. Enjoying “taking materials out of their usual or intended context” is another way in which his designs are unconventional and command interest. At nearly every turn of a corner, the choice of materials and juxtaposition of form and texture are an exercise in discovery. “I want people to see a space reveal itself as they move in it and around it.” • Madeen’s home and studio will be featured in the Durango Parade of Homes in September.

|