| ||

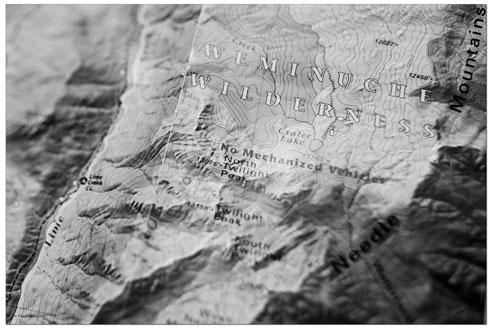

Wilderness in peril

by Will Sands Colorado’s wilds aren’t what they used to be. Barking dogs, garbage and crowded campsites are beginning to encroach into many of Colorado’s designated wilderness areas, and the nearby Weminuche Wilderness is no exception. The local wilderness area was recently named an endangered “magnet area” by the Forest Service during an effort to lighten impacts and reduce damage to Colorado’s most pristine places. The U.S. Congress passed the Wilderness Act in 1964 in order to preserve unspoiled areas “where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” Since that time, more than 105 million acres of public land have been designated as wilderness – places where no roads or permanent structures are allowed, machinery is prohibited and activities like logging, mining and most vehicular traffic is off-limits. However, population growth, urban development and increased visitation may be wilderness’ big threats. Many wilderness areas in Colorado are facing increasing damage from overuse. “Our managers have been raising concerns about increased use and new social trends like litter and crowding,” said Ralph Swain, wilderness program leader for the Forest Service’s Rocky Mountain Region. “There are red flags that are starting to show us that wear and tear is becoming a concern. These are fragile areas.” Steve Smith, assistant regional director for the Wilderness Society, agreed that deeper traces are being left in many of Colorado’s wilderness areas. “There are overworn campsites, a sense of too many people congregating at the tops of peaks, dogs in the wilderness and a whole range of areas where signs of wear are showing up,” he said. Nine of Colorado’s 35 wilderness areas have been listed as threatened “magnet areas” or “hot spots.” Along with places like the Front Range’s Mount. Evans and Indian Peaks wilderness areas and the ever-popular Maroon Bells-Snowmass Wilderness Area. The Weminuche Wilderness Area, northeast of Durango, also has made this list. And though the vast majority of the local wilderness area’s 500,000 acres remain in a pristine state, the draws of 14,000-foot peaks, natural hot springs and trails leading directly into the area have started to do damage. “The Weminuche is an area of concern, but it’s not the whole Weminuche,” Swain said. “There are certain basins in that wilderness area that see high use, particularly Chicago Basin and the Fourteeners there. The Vallecito Trail also gets high use, and on the east side, the Piedra areas sees a lot of traffic because of the hot springs.” In this respect, the Weminuche is representative of all of Colorado’s nine endangered wilderness areas, according to Swain. Certain special characteristics or draws put the areas on the map, and small pieces of the larger wilderness areas begin seeing overuse and abuse. “It’s always some kind of special draw such as a pristine lakes basin, a 14,000-foot peak or some special feature like unusual rock formations,” Swain said. In response to these increases in wear and tear, the Forest Service hosted three Wilderness Forums in 2006. The forums were designed to bring wilderness users, partners and stakeholders together for a dialogue on the future of Colorado wilderness. Three on-site field trips were also conducted last summer to look at impacts in several “magnet areas.” The Forest Service then enlisted the aid of 11 audience members and formed a Core Group last August. This volunteer group has logged thousands of hours analyzing the problems and proposing solutions. The Core Team’s first recommendation is that the Forest Service take a harder look at the “magnet areas.” “One of the recommendations that will come from this group is that we need more analysis,” said Smith, who is also a member of the Core Team. “We need to know how many people go to certain areas, why they are going there and if there are patterns we can observe.” Beyond analysis, the Core Team has also assembled a “menu” of possible fixes for the Forest Service. Among the suggestions are designating campsites, moving certain trailheads, creating a permit system to limit use in certain areas and requiring user registration. “There may also be some things that can be done early to promote ‘leave no trace’ ethics,” Smith said. “On the other end of the spectrum, there may have to be permit requirements to lighten the impacts. There is a menu of options taking shape that the Forest Service should be able to use.” On Feb. 20, Regional Forester Rick Cables will take some time to peruse the menu. At that point, he will sit down with forest supervisors from throughout the state and decide what action, if any, to take. “The regional forester will carefully review the recommendations, but there is no guarantee that he will want to do anything,” Swain said. “At this point, neither the Core Team nor the Forest Service have settled on any given direction.” For their part, Smith and the Wilderness Society are hopeful for the Feb. 20 meeting, and beyond that they have hope for the future of Colorado’s most pristine places. “The conversation has started early enough that we haven’t really lost any wilderness or wilderness character in Colorado,” he said. “I don’t think we’re in a crisis situation here at this time. But we are beginning to see threats to wilderness character. We’re beginning to see more enduring marks from our visits.” •

|

In this week's issue...

- May 15, 2025

- End of the trail

Despite tariff pause, Colorado bike company can’t hang on through supply chain chaos

- May 8, 2025

- Shared pain

Dismal trend highlights need to cut usage in Upper Basin, too

- April 24, 2025

- A tale of two bills

Nuclear gets all the hype, but optimizing infrastructure will have bigger impact