| ||

Taking it izay in Bhutan

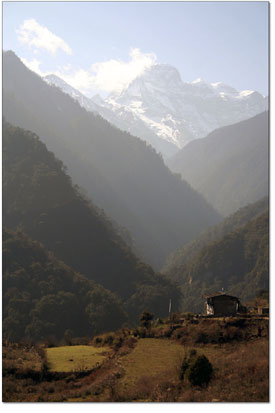

by Chef Boy Ari As our plane made its final approach into the Himalayan Kingdom of Bhutan, the wings nearly scraped the trees off the hills beneath massive snowcapped mountains. I’m leading a group of university students on a quest to learn about Bhutan’s emerging organic agriculture program. If Bhutan’s Ministry of Agriculture has its way, all agriculture in Bhutan will follow organic practices by 2020. So far, only one of the nation’s 20 districts, Gasa, has enacted the switch. Almost all of Gasa is inside the boundaries of Jigme Dorji National Park, Bhutan’s largest. The park contains villages that have existed for centuries, connected by a network of trails. It’s a 10-mile walk to reach the state’s capitol, Gasa Dzong – “Dzong” being the fortress-like structure that houses each district’s political and monastic headquarters. Gasa Dzong sits at about 9,000 feet on a knob with a commanding view of the entire valley and the high, glaciated peaks along the Tibetan border. Today, we started at Gasa Hot Springs, a two-hour walk from Gasa Dzong. During the winter months, Bhutanese from all corners of the country spend days or even weeks there, camping and soaking. At 6 a.m., I counted 21 people, myself included, in a 5-foot-by-10-foot pool. Communication would have been hampered by my limited Dzongkha skills, but most Bhutanese speak some English. And even without words, we still could speak the unspoken language of hot water in the mountains. The previous evening, our guide, Wandga, was soaking in that same pool when he learned of a “nearby” farmer who’d won an international award for high-altitude farming. We made it our project to find her. But first, a breakfast of eggs and izay. A mixture of onions, tomatoes, chili peppers, salt and, depending on the region, other ingredients as well, izay is one way the Bhutanese serve their favorite vegetable: the chili. Yes, the Bhutanese sure love their chili peppers. Of the many names for Bhutan, including “Land of Medicinal Plants” and “Land of the Thunder Dragon,” Bhutan is also known as the “Land of the Three Pains.” These pains, all related to the consumption of chili peppers, can be euphemistically described as an import tax, a processing fee and an export tariff. But the flavor of Bhutanese chilis is addictive, and the associated endorphin rush – a physiological cousin to runner’s high and heroin’s kick – is, well, a rush. The most common way to serve chili is ema-datse, a dish of chilies and cheese hot enough to lure all your facial fluids to a confluence on your chin. This is a main dish, to be eaten with rice, while izay is a condiment, added to augment the main dish. In every place we’ve been, izay is served differently. Some preparations have minced ginger, some feature a crumbled feta-like cheese, some was fried in mustard oil, some was chunky, some pulverized into paste. But in every case, our palates, hooked on capsicum fire, compelled us to reach for the izay and spread it around, despite the pain. Izay on eggs is a great way to fire up your legs for a good day’s walk. It was a two-hour climb to Gasa village, where we located someone willing to show us the way to Rimi, another village, another two-hour walk, where our farmer lived. Her name is Kaka Dema, and she had to drop out of school in the fifth grade when her parents died, and began farming. Starting with an old instructional pamphlet on natural agriculture techniques, Kaka began farming organically before she’d even learned the word, and before it became the law of Gasa. So far from the road, it didn’t make sense to Kaka to haul in expensive fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides – although many other farmers in that region did so. Kaka began learning the life cycles of local pests and experimented with different methods of starting seeds, rotating crops and mulching with composted leaves that had been used as animal bedding. The village school and a local monastery are her main markets. The diversity and quality of her produce caught the eye of local administrators, who nominated her for the “2004 UN Highland Farming Award,” which she was flown to Thailand to receive when she was 23 years old. She showed us her medal, which she keeps in an old suitcase. We drank butter tea in the wood-and-stone house she shares with her husband, son, aunt and uncle, and she told us she grows all of their food except salt, oil and rice. With darkness just hours away and 12 miles to go before we could sleep, we bid Kaka farewell and trotted down the mountain, past the eerie sounds of horn-blowing monks at the monastery that purchases Kaka’s food. At a little shop by a footbridge over a roaring blue river, we munched on pieces of boiled leather that had marinated in izay. The spicy leather was soft, unlike the hands of the farmer that we’d traveled around the world to find. •

|