| ||||||

Cut in Wood

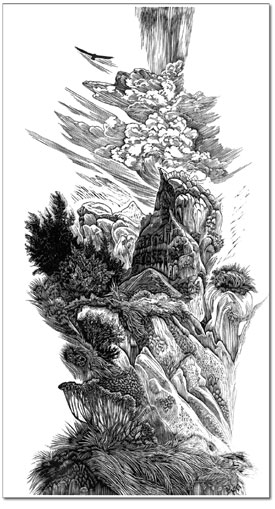

by Jules Masterjohn Siri Beckman was “called” as a young woman, not to “the cloth” as the term often implies but to become an artist. Beckman’s life-long medium of choice is very hard wood. Beckman is not a sculptor, carving wood into three-dimensional forms, but a printmaker who cuts images into a wooden block’s surface. From this incised block she makes her wood-engraved prints. In her exhibition, “,” currently on display at the Durango Arts Center, Beckman presents 13 exquisite wood engravings, images of the East Coast and Western landscapes, and scenes from daily life. Wood engraving, a relatively unknown technique today, was invented in England in the late 18th century and, within a hundred years, became the standard method used to create illustrations for books and magazines. With the invention of the camera and routine uses of photographic processes, wood engraving fell from popular use. During the 20th century, artists like Beckman revived the process to create fine art prints. Generally more familiar to us is wood engraving’s sister process, wood-cut printing. Probably even more well known is making prints cut from linoleum. And most of us, or our children, have experienced making potato prints in elementary school. All these methods are types of relief printing, in which material is removed from a block to create an image. When ink is applied to the block, and paper is laid onto the inked block and rubbed, an image is transferred to the paper. Every place the wood, linoleum or vegetable matter has been removed, shows up on the paper as white. Relief prints have a “look” that is recognizable: the images are graphic and show two contrasting values. Traditionally, the blocks are printed with black ink onto white paper. In Beckman’s wood engraving process, with specially designed engraving tools, she cuts fine curls of wood out of the endgrain of English boxwood, an extremely dense, hard wood. For the artist, this is not a difficult endeavor, rather, she enjoys the challenge. “It is such a different experience than drawing, to push a tool through a resistant material. I can’t do with a pen what I can do with an engraving tool and I am not as confident about my drawn line. Wood engraving really interests me,” she said. When one knows a bit about the process, it is nearly inconceivable to imagine that one of Beckman’s works, “Pinnacles,” was produced by making hundreds of miniscule incisions into the hard endgrain of a block of wood. Beckman explained, “Cutting on the endgrain allows a fluidity not present in wood-cut prints, which are cut on the plank side of the wood using wood gouges.” This flowing quality, especially evident in “Pinnacles,” is the result of 40 to 50 hours of work. A deliberate, precise and slow process, wood engraving is not well suited for the restless of heart or hand. Beckman is neither.

“Pinnacles” was created from sketches that she made while on a one-month artist residency at Badlands National Park in 2002. She spent her 30 days wandering, drawing and “letting the subtle textures and colors soak in.” When she began to engrave the block for “Pinnacles,” she didn’t know where the composition was going. She abandoned her usual process of transferring a sketch onto the wood block and mapping out, in a broad way, the different areas of light and dark values. With this piece, she just kept working, making incisions into the wood. The result is a Badlands landscape, filled with incredible details and textures, depicting abundant life in what one might have imagined as an arid and, thus, barren ecosystem. From Beckman’s perspective, nothing could be further from the truth. Each aspect of the land she portrays seems to be moving, breathing almost, and a sense of aliveness is everywhere. From the waving grasses in the foreground and the muscular pinnacle in the center to the soaring raptor rising high above the anvil-like cloud formations, there is a magical quality to this work. Merge Beckman’s 25 years of wood engraving with a master’s degree in printmaking and a dedication to paying close attention to what is around her, and we have, living among us, a master technician and true artist. She engages the viewer with her accomplished artistic abilities: her compositions are interestingly designed and her printmaking techniques are impeccable. Beyond these qualities, there is another characteristic that is present in Beckman’s work that cannot be learned. It is perhaps born with the person who is destined to be an artist. It is the ability to imbue one’s creative works with soul, a quality that is difficult to describe in words, yet I will attempt it: “Soulfulness” in the arts involves a communication of profound depth, from the artist through the artwork to the viewer. This April, Beckman will leave Durango, as she has done for the last four years, to return to her home of 25 years in Stonington, Maine, for the summer and early fall. She will return to Durango again, hopefully, in October, for she is falling in love with the West. •

|