| ||||

"Right livelihood"

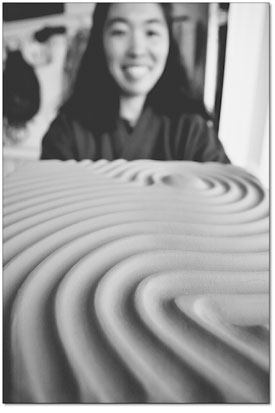

by Shawna Bethell Upon entering the home of potter and teacher Chyako Hashimoto, you are immediately surrounded by forms and images created by the artist. Elegant, flat disks of coral and russet swept with watermark-type accents of deep blue or purple, large white sculptures that bring to mind sea anemones, and shimmering paper thin vase-like forms of rich blue and violet all catch the eye of a visitor. Each shift in style represents growth of the artist or curiosity from this Durango woman who is reaching new levels in her mastery. But when Hashimoto takes her guests into her kitchen and opens the cabinets, lifts out an earthen bowl or plate and holds it out to willing hands, the simplicity and balance of the artist comes full circle. “It is the empty space that makes a cup or bowl useful,” she says. “We must consider the beauty that is found in the absence of things.” These are the types of lessons that come from taking a pottery class with Hashimoto. Students learn from the beginning how to wedge clay, center a piece on the wheel and create various forms, lessons typical of any pottery class. But what stands out in these particular classes is that for 20 minutes of each period, students are walked through a meditation starting with relaxation and breathing, then moving to grounding and centering the body. Students are asked to count breaths or listen to the sounds around them without trying to identify the sounds, only hearing them and then releasing them. Thoughts that come to mind are acknowledged, then like the sound, they are released. Once students are settled, or centered, they are brought quietly “back” to class by opening their eyes. The idea behind the meditations is that students cannot center their work without being centered themselves. “This is the first year I’ve really tied the two together,” says Hashimoto who teaches classes at Fort Lewis College and at the Smiley Building. “I wasn’t sure how people would accept a spiritual approach.” In comparing the classes and students’ acceptance of her new methodology, she says the students at Fort Lewis are initially more receptive to the idea of meditation within the class, but they aren’t necessarily “ready to take it on,” whereas the people in the community who take the classes at the Smiley Building are more apt to “sit down and make it their own.” “When students come in to class, when we gather, it’s not a great place to start working from,” she says. “There is a lot of distraction, a lot of chatter, even the wanting to make something specific becomes a distraction.” And so, Hashimoto came up with the idea of meditation. “We all have the means and the time to be creative,” she muses, “but we also have the distraction to gain, whether it is the gaining of ideas or materials. We do the meditation to prepare to listen.”

Hashimoto does not necessarily mean listening to the teacher, but listening to that place of creativity within ourselves. It goes back to that earthen bowl; the beauty is in the empty space because it is the space that allows for something, creativity in this case, to enter in. “I don’t want to be preachy,” says the artist. “But I do play that line. I meet spirituality through the back door. Art is the medium for people to enter their own spirituality.” Hashimoto says that many things: exercise, nature, poetry, as well as art, are all back doors. Art is what opened that door for her, and there are different avenues for different people. Once that door opened for her, spirit became more important than art, and her teaching methods reflected that change. There is a Buddhist term, “right livelihood,” that reflects the ideology. Hashimoto describes it as looking at how we relate to the world and not separating our work from life. “It is interconnectedness,” she explains. “We are all part of the world, everything we say, everything we do. It is about looking into the world and being willing to take action to create good things, to not do things that create bad karma.” It has become a lifestyle for Hashimoto that came about much like her artwork, without necessarily a conscious decision but an organic evolution of her perspective. “Everything I do evolves inside out,” she says. “I move from intuition to intellect whereas many artists move from intellect to intuition. They try to think of ideas to express. I prefer to let things sort themselves out and am willing to commit to the process, the ritual, of letting things express themselves.” In her own artwork, Hashimoto has felt a similar evolution as with her teaching. Early in her career, she decided she did not want to be confined to the limitations of functional pottery such as cups and bowls. She wanted to stretch the bounds of size and shape to explore both her own talent and what clay can do as a medium. But like her teaching, her clay work has come back to the elemental and she finds she resonates with the simplicity and earthy textures of functional pottery. “Creating pottery that people can use daily is a way of connecting to people. It is a way of bringing it back to the community, which is part of the essence of ‘right livelihood.’ The time is over for me to say, ‘Look at me. This is what I can do.’ Now it is about community, passing the philosophy on to students and allowing them to follow their own evolution of creativity through meditation.” •

|