| ||||

| Ghosts of Gonzo resurrected Aspen Institute hosts first annual Gonzo Symposium SideStory: Going public with the Gonzo Symposium

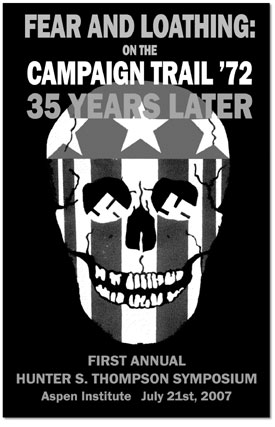

by Katie Clancy On July 21 and 22, the two days when Dick Cheney had claims to the tattered presidential throne courtesy of George W. Bush’s rectal condition, Hunter S. Thompson also was honored as one of the greatest American journalists of the 20th century. Close friends, freaky fans and fellow comrades gathered in Aspen at the Aspen Institute for the first annual Gonzo Symposium. Although Thompson killed himself more than two years ago, “his writing is very much alive,” said Dr. Bob Geiger, to whom Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is dedicated. Thompson’s idea of a good time during these kinds of formal events would probably involve smoking out the staid environment with tear-gas and fireworks. But in his introduction, Thompson’s son, Juan, reminded participants that it was not the day to glorify his Mad Doctor persona. “His legacy as a wildman needs no help from me.” Thompson said. “He was a complex journalist, person and father. We are here to jumpstart my father’s legacy as a serious American writer.” Thompson and the Aspen Institute’s goal was to revisit Thompson’s writing in two moderated sessions of panel discussions (one in the afternoon and one in the evening) about Thompson’s third book, Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72. Historian and journalist Douglas Brinkley, whose most recent book is entitled The Great Deluge: Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans, and the Mississippi Gulf Coast, moderated the afternoon discussion in front of an exclusive audience of less than 100 press members, colleagues and friends. Most of the panelists themselves had been lifelong friends and colleagues of Thompson – Ed Bastien, Carl Bernstein, Curtis Robinson, Gerry Goldstein and Loren Jenkins. Others, such as actress Anna Deavere Smith, professor Audrey Sprenger and political journalists John Nichols and Michael Isikoff, had only met Thompson through his writings. “Dr. Thompson’s” honorary name plate and a silver cardboard cutout of the gonzo-fist-sword stood at the head of the semi-circle. Brinkley hailed Thompson as the master of his craft – from the rhythm (Thompson played the air drums whenever he heard his work read out loud), word choice and fine-tuned introductions. “He worked hard. He was a merciless self-critic and read voraciously.” Legendery journalist Bernstein, who broke the story of the Watergate scandal, accredited Thompson’s career to such classic writers as Norman Mailer in “Armies of the Night” and Tom Wolff. “Good journalism is obtaining the best possible version of news,” he said. “These three men relied on independent verification, contextual research, acute observations and the rejection of mindless objectivity.” Panelists called Thompson many names – anarchist, lover of America, master wordsmith, old-testament prophet, iconoclast, celebrity, hermit, heat-seeking missile – but Anna Deavere Smith’s comparison to a Brechtian actor resonated. “Method actors believe they are the characters they portray. Brechtians take on the persona but are fully aware that they are separate from their characters,” she explained. “In his writing, Thompson presented the possibility of experiencing other worlds and characters while maintaining a journalist’s distance.”

With this critical eye and with wobbly knees, Thompson raged defiantly in the face of authority. Bastien, a Buddhist studies doctorate and Thompson’s advisor during the ’70s sheriff campaign, reiterated Thompson’s desire to uncover the truth, so often buried under conventional wisdom and the masks of the powerful and elite. “He detested ‘The Lie,’ and the people who pretended they knew the truth. He had no patience for people who believed their own lies.” The discussion turned to how Thompson’s approach to journalism is critical today. “Part of Hunter’s mission was to redeem journalism from itself. He saw the danger of a dumbed-down, corporate conglomeration. Part of the problem stems from reporters who write for people who are interested in politics. By that, we are killing the craft. Gonzo journalism spoke to readers even if they didn’t give a damn about politics and politicians,” Nichols said. As a result, Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72 exposed what Bastien called the “Kabuki theatre of politics” to the American public. “On the day the leaders catch up with the citizens, excerpts from Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail will be read at the presidential inauguration,” Nichols said. But perhaps it will be the unpublished work that will best continue Thompson’s legacy. “Thompson wanted to be a novelist. There are a series of short stories, in particular one titled ‘Prince Jellyfish’ that Thompson wrote when he was younger that will be published,” Brinkley said. In the July 21 “Gonzo Edition” of The Aspen Daily News (the cover was a Steadman cartoon sketch of Thompson disguised as Harry Potter), Thompson’s short story “Fire in the Nuts” was featured. Near the end of the two-hour discussion, Isikoff expressed frustration about the fragmentation of news sources and opinions circulating on the internet and blogospheres. “People read what conforms to their own biases. This makes it hard to find a common dialogue.” Smith responded to Isikoff by reading aloud two passages from Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail. The first was former U.S. congressman and current mayor of Oakland Ron Dellum’s voter theory, which Dellum calls the “nigger vote,” consisting of all who have been marginalized in society. The second passage was about an encounter with Hunter and a “befuddled old darkie” bell-hop for whom Hunter fills a cup of bourbon. Though the message is complex, Thompson flashed on a truth: We are condemned to repeat our history until we fill enough cups for all the voiceless Americans who have been left out. Until blogospheres and the internet, that is. In citing these passages, Smith challenged Isikoff’s frustration: today, anybody with a computer and internet line can report his or her truth. “If I could ask Hunter one thing, I would ask him about race. Who can say what for whom?” The well-dressed Caucasian audience applauded. As if on cue, black thunderclouds descended over the mountains during the interim. Enter the ghosts of Gonzo. Hail and wind blasted through the building, knocking over white lilies and shattering the crystal vases. “Hunter was a warrior above all. He used words and writing as a sword to change the world,” Juan Thompson said. •

|

In this week's issue...

- May 15, 2025

- End of the trail

Despite tariff pause, Colorado bike company can’t hang on through supply chain chaos

- May 8, 2025

- Shared pain

Dismal trend highlights need to cut usage in Upper Basin, too

- April 24, 2025

- A tale of two bills

Nuclear gets all the hype, but optimizing infrastructure will have bigger impact