| ||

| Two decades of Montessori in Durango Children’s House celebrates 20th anniversary SideStory: A brief history of Children’s House

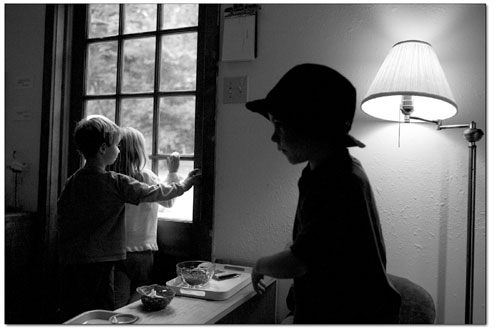

by Judith Reynolds They don’t advertise. They don’t have to. Children’s House, Durango’s own Montessori preschool, turns 20 this fall. To celebrate the anniversary, Director Alicia Zepeda is inviting alumni, students, staff,and friends to a barbeque at 4 p.m., Saturday, Sept. 23. Bring a dish to share. Two decades of creating a learning and discovery environment for the youngest of our citizens is no small accomplishment. “We have a long waiting list,” Zepeda said in an interview last week. “It’s all word of mouth, two generations in some families. Others hear about us and want to enroll their children.” Why so successful? Montessori schools have a unique curriculum. Derived from Dr. Maria Montessori (1870 – 1952), the schools are an outgrowth of their founder’s life-long passion for observing how children learn. As Italy’s first female physician, Montessori began her career in the field of children with disabilities. She noted how innate inquisitiveness helped many overcome obstacles. So powerful was her experience, Montessori left behind her medical practice and her professorship at the University of Rome to establish Casa Dei Bambini in 1907. Situated in a poor district of Rome, the house became an educational center for young children. It was here that Montessori put into practice her methods for capitalizing on a child’s natural ability to observe, explore and learn from the environment. She developed materials and processes that became known as the Montessori Method. At its core is the belief that children teach themselves – if allowed. Montessori’s educational reforms spread. In 1913, she made her first visit to the United States where none other than Alexander Graham Bell and his wife, Mabel, founded the first Montessori Educational Association. In 1915, her Glass House Schoolroom at San Francisco’s International Exhibition extended Montessori influence. Schools sprouted up around the globe as her progressive ideas spread. In 1929, Montessori established an international association that continues today. But Montessori’s belief in the independent individual also ran into Mussolini’s fascism, she had to flee the country in 1934. Two years later, she brieflysettled in Spain until the Civil War forced her to flee again, this time to India. There she remained until the end of World War II. Afterwards, Montessori resumed her life work and established schools in various parts of Europe. Nominated for the Nobel Peace Price in 1949, ’50 and ’51, she died the following year. If you step into Durango’s Children’s House on West Third Avenue, you can see Montessori’s legacy. Last week in one sun-drenched corner, four kindergartners sat at a low table busily writing stories. Another small group discussed the possibilities of drawing a chocolate horse. One 5-year-old finished her drawing, quietly got up and said, “Excuse me.” She pushed her chair back under the table and walked over to a huge basket of dried beans. “Brrrrrr,” she trilled as she lifted a bowlful of beans and tumbled them back into the basket, mimicking the sound. “Scoop,” she said to herself as she cascaded more beans down into the bowl using a plastic measure. “Bury,” she whispered as she pressed a small bowl deep into the basket. Then she returned to her group table, pulled out a new sheet of drawing paper and began a new picture. This small episode demonstrated several of Montessori’s basic beliefs about children and learning: a fundamental curiosity, self-direction and courtesy. All this took place in the sunny Rainbow Room at the back of Children’s House. You can see the same level of concentration and purposefulness in the Red, Green, Blue and Pink rooms. Each is lined with low shelves and a selection of neatly placed games, puzzles, household objects, and musical and reading materials. The art room has easels for painting and tables for other art activities. Another room houses maps and globes. The Bin Room has separate compartments for each child’s belongings. Spacious floor areas accommodate shared activities. Small tables and chairs invite solitary exploration. In the Blue Room, 3-year-olds carefully stack rings, tower blocks or quietly observe the fish bowl. Four-year-olds worked puzzles, together or alone. Elsewhere a pair of 5-year-olds took turns without interrupting, trying to solve a problem. “No one is bored,” Zepeda said. “Our goal is to create an environment where the children choose what they do with their time.” The emphasis is on independence and respect, she said, for one’s self, others, the materials at hand, and the environment. For the youngest children, learning practical skills is a daily affair – pouring water, carrying a chair or cleaning up after oneself. These activities involve eye-hand coordination and social awareness. No matter how ordinary, every activity is seen in the larger context of developing concentration and independence. “In Montessori training,” Zepeda said, “we learn that there are great leaps of learning in certain periods in childhood. At those times, children learn effortlessly, and we want to be prepared for that. We (teachers) spend a lot of time observing and taking notes. We’re interested in how individual children make choices and how they go about doing things, how they sequence left to right. We notice when they are interested and focused or distracted. Our materials are designed for self teaching and are also self correcting. We even encourage making mistakes. That’s learning, too.” •

|

In this week's issue...

- May 15, 2025

- End of the trail

Despite tariff pause, Colorado bike company can’t hang on through supply chain chaos

- May 8, 2025

- Shared pain

Dismal trend highlights need to cut usage in Upper Basin, too

- April 24, 2025

- A tale of two bills

Nuclear gets all the hype, but optimizing infrastructure will have bigger impact