| ||

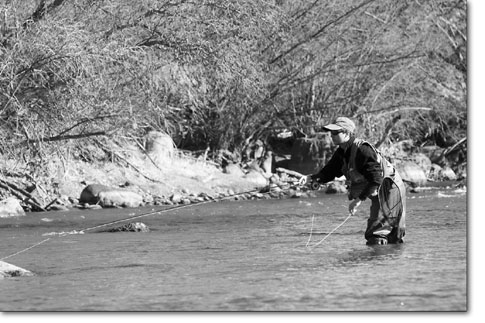

| Weighing the health of the Animas Local fishery sees improvement but faces new challenges SideStory: Give something back to the Animas

by Will Sands Trout are like the canaries in the coal mine for Buck Skillen, board member of the local Five Rivers Chapter of Trout Unlimited. “Everyone in this town should be vitally interested in the health of our rivers and streams,” he said. “If it’s good for the fish, it’s good for the rest of us. If we lose our fish, we’re severely up the creek.” Right now, the canary seems to be thriving in the Animas River and throughout the Durango area. Continued clean-up of mine waste around Silverton has enhanced water quality on local rivers, and the population of trout between 32nd Street and the new Rivera Crossing Bridge, across form the Purple Cliffs, is booming. However, Skillen and others are keeping a close eye on the future and new threats to the health of local rivers and fish. The Colorado Division of Wildlife has been monitoring stream health on locations on the upper Animas River for nearly 15 years. Mike Japhet, DOW aquatic biologist, describes a site just south of Silverton as “ground zero” for heavy metals loading on the Animas River. “In 1992, we found not a single fish in that section of the Animas. It was probably ground zero for water-quality problems on the river,” he says. Last year, the Division had a breakthrough on that section of the river. “In 2005, we were pleasantly surprised to collect one, single, lonely brook trout in that section,” Japhet said. While one fish may not seem like a breakthrough, the find represented huge progress. “It’s subtle,” Japhet said. “There hasn’t been a striking turnaround, but we’re finding fish where we haven’t seen them before, and we’re seeing greatly improved body conditions on the fish we’re finding.” Japhet and others give credit to the tireless work of the Animas River Stakeholders Group, a consortium of agencies and individuals that has worked for the last decade to clean up the polluting, old mines and adits in the Silverton area. “What we see on the river in Durango is dependant on what’s going on upstream,” Japhet said. “The Animas River Stakeholders Group has been working on trying to improve that water quality in the headwaters of the Animas for a long time.” Skillen agreed, saying, “The Animas River Stakeholders Group is largely responsible for the health of the river. The river today is much healthier than it was 25 or 30 years ago.” Chuck Wanner, water issues coordinator with San Juan Citizens Alliance, also gave credit where credit is due. “The traditional challenge has always been the legacy of mining in the Silverton area,” he said. “The Animas River Stakeholders Group has done many things and spent many millions of dollars to improve water quality in the upper Animas River basin.” Many thousands of hours and millions of dollars may have translated into a single brook trout near Silverton. Downstream in Durango, the work has helped lead to the existence of a world class fishery, a section of Gold Medal Waters stretching between Lightner Creek and the Rivera Crossing bridge and a section that meets Gold Medal criteria but has not been classified between 32nd and Ninth streets. However, the health of the Animas River as it flows through Durango was also put to the test following the wildfires of 2002. “We had a short-term event that fall when the Animas bumped up to a 4,000 cubic feet per second after running just over a hundred during a very hot summer,” Skillen said. “Plus, we had big mud flows come down. I was very fearful that we’d lost our fishery during that event.” The Division of Wildlife was also fearful, and shortly after the high, muddy waters receded, the agency conducted a fish census on the Animas River. “We found that the Gold Medal criteria were still being met,” Japhet said. “Actually, the section running through the heart of Durango also qualifies as Gold Medal water even though it isn’t designated as such. To me, that indicates that the fishery is a healthy one.” Natural reproduction is still lagging on the Animas, however. Each year, the DOW introduces 40,000 fingerling trout into the river to compensate for difficulty with natural spawning because of residual metal load. However, Japhet said that he expects that picture to improve as well. “As time goes on and the water-quality cleanup in the headwaters makes even more progress, we expect to see more and more natural reproduction,” he said. While water quality may be on the mend in the mining-damaged areas around Silverton, there are new threats appearing that could damage river health in the Durango area. Japhet argued that whirling disease is one of his major concerns. “One of the big question marks is, ‘What is whirling disease going to do?’” he said. “We have had whirling disease in the Animas River since 1996, but the disease doesn’t appear to be exercising any population-level impacts. But there is always a potential for flare-up with the disease.” As construction on the Animas-La Plata project continues to progress southwest of Durango, it also poses a threat to the fishery. The water project will siphon water from the Animas during high flows and pump it into a reservoir in Ridges Basin high above the river. A-LP is not expected to impact the Gold Medal waters south of the diversion near Santa Rita Park, according to Japhet. However, diminished flows combined with warm temperatures could harm the river between Bodo Park and the New Mexico state line. “If we see water temperatures climb a few degrees, it could create conditions that are favorable for warm water fish like smallmouth bass,” he said. “We’ve seen negative impacts from illegal or accidental introduction elsewhere in the state, and it is possible here.” A boom in real estate and development throughout La Plata County could also negatively impact aquatic life in local rivers. Fertilizer run-off from golf courses, excessive stormwater and sediment load could all damage the Animas River and the fish living in it. “The big thing now is development,” Wanner said. “What will development do over time and how will we manage the waste we produce?” Wanner added that the impacts of human growth are showing up in unexpected places in the natural world. New pollutants from household cleansers, medicines and cosmetics are being found in fish and rivers. “Those new pollutants are a concern,” he said. “A lot of them are chemicals we don’t have any way of treating.” And development outside of La Plata County could have negative repercussions on local rivers. Water is relatively abundant in the Animas River watershed and could be transported via transmountain diversion to the thirsty Front Range if it ever becomes economically viable. “A reliable source once told me that there are currently enough water rights available to put a house on every acre of La Plata County,” Skillen said. “But the truth is there aren’t a lot of places left to put housing and major industry. Potentially this area could be looked at as a future source of water for other basins.” However, Skillen has high hopes for the future of the local fishery, even though he doesn’t care for the word, saying, “I have a problem with the word ‘fishery.’ People perceive that fishermen are being selfish with our rivers because we want to fish them. It’s a larger picture beginning at the most basic microscopic level and stretching up to us at the top of food chain.” Japhet and Wanner agreed that everyone, not just fishermen and boaters, has a stake in the Animas River, and everyone has a responsibility to care for it. “It’s a resource we all enjoy,” Japhet said. “It’s something that defines Durango, and it’s in all our best interests to take care of the river and the fish that live in it.” Wanner added, “If we stay on our toes, the future’s bright. So far, we haven’t messed up the water quality on the river beyond the point of reclaiming it.” •

|

In this week's issue...

- May 15, 2025

- End of the trail

Despite tariff pause, Colorado bike company can’t hang on through supply chain chaos

- May 8, 2025

- Shared pain

Dismal trend highlights need to cut usage in Upper Basin, too

- April 24, 2025

- A tale of two bills

Nuclear gets all the hype, but optimizing infrastructure will have bigger impact