| ||

‘El Inmigrante’ heads home

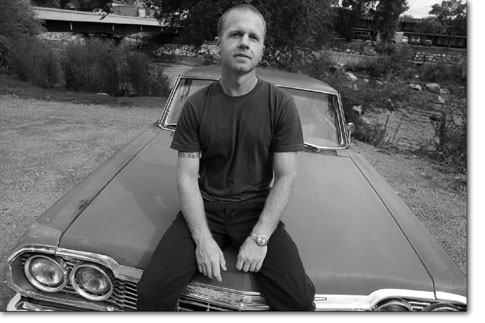

by Shawna Bethell "I just had a gut feeling that this was the right film at the right time. There was never a question. I knew this was going to go somewhere.” The passion Durango filmmaker John Sheedy has for his film, “El Inmigrante,” is unmistakable as he sits forward on a couch at the Steaming Bean, elbows on his knees. As with most artists, he hopes the film, which he made with local brothers David and John Eckenrode, will be picked up by a distributor and “go big.” But in his heart, he knows the most important audience for “El Inmigrante” is a family in Mexico who lost their son to American racism and violence. So packing up his classic brick-colored Impala, Sheedy and photographer Amy Iwasaki recently took the film home to the people most affected by border issues. For two months, they showed the film in migrant centers, theatres and finally the National Museum of Popular Culture in Mexico City. The film has been lauded by activists, intellectuals and the migrants who risk everything to get to this country. And the family of the film’s subject, Eusebio de Haro Espinosa – a young man who was shot from behind by an elderly white man in the borderlands of Texas – could finally see that something positive may have come from their pain. The murder and the miscarriage of justice surrounding Eusubio’s murder made headlines. With “El Inmigrante,” which won best documentary at the Harlem International Film Festival last summer, Sheedy and the Eckenrodes took the news story and created a poignant exposé of border relations and racism. By spending time with the family of Eusebio, border patrols, vigilantes and the migrants themselves, the film delves into why so many Mexican people are willing to risk everything to get to America. “When we showed the film at the CAME migrant center in Agua Prieta, there were about 60 immigrants who were preparing to cross or had crossed that day and been returned by the border patrol,” said Iwasaki. “They were just so tired, but you could tell it touched home.” Sheedy added, “I looked around the room at their faces. You could tell they were absorbing it, nodding their heads. It was like there was validity to what they were experiencing.” In contrast to the CAME center, there was a lot of “big talk” in Mexico City, according to Sheedy. There was a great deal of intellectual discussion on the issue, which is a distant one for many of the people in urban Mexico. “During the time when the director (Sheedy) was speaking,” said Iwasaki, “one woman wanted to know what they could do. It was like they were looking to him saying ‘Give us the answers.’” “But I am not in a position of authority,” said Sheedy. “I’m not an expert. I just want to tell the story and start the dialogue.” That is what happened in most venues where the film was shown. Dialogue and discussion always took place, sometimes heated, sometimes indignant, but always passionate. Sheedy and Iwasaki recounted stories of another woman who told how she had seen immigration destroy families she knew. A man, a gringo, in San Miguel Allende demanded to know what Sheedy would do if he were God and could fix the problem. There were accusations of American racism and the filmmakers exploiting the Mexican people. There were people moved to tears at the poignancy of the story. “There was one old man, an American ex-patriot, sitting in the front row at San Miguel Allende,” recalled Sheedy. “He was crying his eyes out.” A moment later, he added, “I’m happier seeing the emotional outbursts or debate instead of everyone agreeing with the film.” The Santa Ana Theatre in San Miguel Allende sold out showings three nights in a row and will continue to show the film once a month for as long as people will come to see it. “El Inmigrante” took the record for ticket sales in the artists’ community, impressive given that word of mouth was the only advertising the showings really had. It represents the life that the film has taken for its own. The emotion, the power of the film, has almost overwhelmed the people involved, Sheedy said. Everywhere they went, they were handed cards and phone numbers, contacts for people who “should see the film.” Here in the United States, the momentum of the film is no less inspiring. It has been picked up by eight different film festivals including the Amnesty International Film Fest in Seattle and the same organization’s festival in Asheville, N.C. It also is being used in classes at Ventura College in California and has been requested for use at Amherst College in Massachusetts. The filmmakers are still hopeful that a large distributor will pick up “El Inmigrante.” They want the story to reach larger audiences. But in a tiny living room in San Felipe, Mexico, surrounded by the family of Eusebio, Sheedy and Iwasaki felt the real success of the film. “They were laughing, seeing themselves on TV, but as it progressed, the expression on the mother’s face, I’ve never seen it before. The boys were on the edge of their seats. It was incredible seeing their faces,” said Sheedy, who has remained close to the family. “When it was finished, Eusebio’s father, Pasiano, who felt the film was destined to be made, stated that it was a great documentary.” Sheedy concluded, “To have both emotions from one film, the laughing and the sadness, I see that as successful film.” •

|