|

| ||||||

| A brief history of barbering

by Jeff Mannix Men have always preened for the fairer sex and to distinguish themselves among their peers. Historically, the barber shop has been the bastion of civility. Tonsorial artists have maintained the dignified appearance of men dating back to 300 B.C. Through the centuries, barbers routinely shaved faces, trimmed beards, cut hair (tonsura), pulled teeth, cast broken bones and bled customers who suffered from somatic distress of any nature. The ubiquitous barber pole became a graphic depiction of the blood-stained gauze bandages barbers would wrap around the vertical roof pole outside their shops to dry. Times change. The barber/surgeon was replaced first in England by the emerging medical profession in 1745. Face hair went in and out of fashion, beginning with Alexander the Great after losing important battles to unprincipled Persians who grabbed their beards. Wigs became de rigueur throughout Europe in the 18th century. Gillette invented the safety razor early in the 20th century. Then the Beetles appeared on the scene in the 1960s with mops of hair, casting the final blow to what had theretofore been a trade as necessary as greengrocers, butchers, tailors and shoemakers. Here in Durango, where once there were 15 or more barber shops situated on Main Avenue among four pool halls, gin mills and gambling parlors, there are now only three genuine men’s barber shops. Durango supports 292 licensed cosmetologists (beauticians), but only 10 active barber licenses, of which only three operate in men-only barber shops. Only two of those conform to traditional walk-in service. Amador Tucson has been guiding the clippers and wielding the sheers for 34 years at his 10-by-27-foot shop next to the old post office. He is such a Durango institution that some call him the mayor of Main Avenue. At 66 years old, Amador is the reigning barber in Durango. He knows who the players are and where the bodies are buried. Like all barbers, he’s listening but not talking. “I wake up early, 5 o’clock, walk from my house down to the river trail, up to the high school, then down to the shop to open at 8. I love this town, my hometown, and I love what it’s becoming. It’s a great place filled with great people,” Tucson pontificates as he busies himself sweeping hair into a dustpan and then brushing clippings out of one of the half-dozen pairs of clippers lined up like soldiers. “You know, some people hate their jobs – I hear it every day,” Tucson continues. “Me, I love coming to work. I love this job. I never wanted to do anything else.” Tony Gallegos has been on the job for 30 years in his present location in College Plaza. His brother is a barber; his sister is a beautician; and he has uncles and cousins in the hair business. He comes by the trade naturally, and naturally, like the other genuine barbers in town, he loves his work and enjoys his customers. “I used to sell newspapers when I was a kid, for the Basin Star. I’d sell the papers for a dime and pocket a nickel. I’d sell a hundred papers a day, then go down in front of the Strater Hotel and shine shoes after school and on the weekends,” Gallegos boasts.

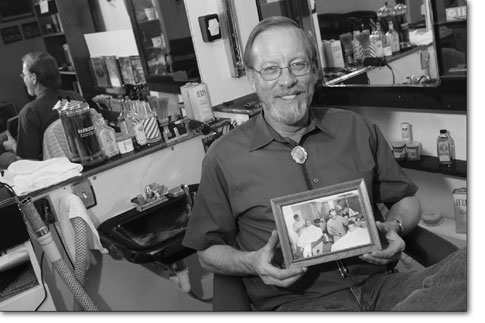

Rod Wenzel has been barbering in Durango since 1977, first at the West Building on E. Second Avenue, then 15 years on Ninth Street under the Elks Club, and for the past 13 years in the alley behind the 20th block of Main. His father, Ray, barbered for 35 years before him. “It takes about five years to learn how to cut hair, and that’s after 1,200 hours in barber school,” Rod says with more than a modicum of pride. “After you get the hang of it, the job is dealing with all kinds of people. You have to like people to be a barber; once they’re in the chair, it’s all about them. If you’re good – with hair and conversation – they’ll come back. My customers come back.” Wenzel beams with an infectious smile, the hand gestures of a card shark and the arrogant humility of a professional class of worker who’s at the top of his game. The barber trade hit its stride in Durango in the 1930s when the Crystal and the Strater Hotel shops merged to form the 10-chair Sanitary Barbershop on the east side of the 900 block of Main. In those days, and in fact up until 1973, barbers graduating barber school were required to serve a one-year apprenticeship under a master barber, and the Sanitary Barbershop became a breeding ground for new recruits. The shop was narrow and long, with the alley end devoted to public bath tubs. For a quarter, men could have a bath drawn with clean water, and for a nickel … well, you get the picture. It was a place where businessmen would come in every day or two for a shave and have their boots shined, or railroad men and miners who’d been up in the mountains for weeks could walk out with an entirely new veneer. “We didn’t care what they looked like when they came in,” says Tucson, who apprenticed with master barber Tom Stull, the owner of the front five chairs at the Sanitary. “But we wouldn’t service drunks. If they even smelled of alcohol, we would turn ’em back out on the street. Nobody serviced drunks, but we’d clean up the worst-looking guys and turn them out for a good night on the town.” Melvin T. Smilie graduated barber school in Kansas City, Mo., in 1935 then worked at Sanitary for 40 years, eventually owning the back five chairs with Reene Folks. “We did lots of shaving, about as much as hair cutting back in those days. Then during the war and just after, we did lots of flattops – I could cut a pretty good flattop in those days,” Smilie, the oldest barber in Durango, recalls with a hawk’s gaze and the steady hands, at 94, of a man who has pressed a razor to men’s throats for almost half his life. There’s a noble history in barbering, and all three of the shops in town display antiquities of the trade: straight razors of evolving styles and exotic materials, leather straps, old clippers, scissors, decades of gossip, and barber chairs dating back 80 years and weighing 250 pounds. More than just a job, it’s a way of life. And when these three men retire – and they all have that day in view – Durango will have lost its last remnants of a bygone time when men were pampered with camaraderie, politics, the unforgettable fragrances of witch hazel, Clubman talc, newsprint, cigars, and the deft hands and agreeable conversation of a class of dedicated professionals for which the 21st century hasn’t the taste. •

|

In this week's issue...

- May 15, 2025

- End of the trail

Despite tariff pause, Colorado bike company can’t hang on through supply chain chaos

- May 8, 2025

- Shared pain

Dismal trend highlights need to cut usage in Upper Basin, too

- April 24, 2025

- A tale of two bills

Nuclear gets all the hype, but optimizing infrastructure will have bigger impact