| ||

A visit with the Missionary Muse

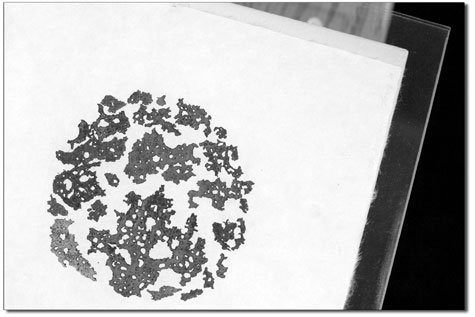

by Jules Masterjohn Many artists wear two hats: one as the image-maker and the other as a content maker. Successfully combined, both image and substance – what we see and what it means to us – serve the artwork in its role as a meaningful object. The visual language that an artist uses is often symbolic, metaphoric, and personal. There are times when an artist’s vocabulary is nuanced and may be difficult to decipher. When encountering an artwork that is perplexing, a viewer often benefits by approaching the art with openness and curiosity: What is the artist is trying to ‘say?’ Having the time to spend and contemplate art can be of great value in understanding an artist’s lexicon and the more subtle meaning in her or his visual communications. A impressive example of how different artists ‘speak’ of the same subject can be seen in the show, “Missionary Muse,” currently on display upstairs in the Durango Arts Center’s Art Library. With walls bordered by art books and magazines, the Art Library is an intimate exhibition space, one that suits this quiet show about a very public event, the Missionary Ridge Fire of 2002. Mixed media sculptor and book artist Mary Ellen Long and photographer Chet Anderson combine their work in an exhibit that speaks of their experiences in the burn zone after the fire as well as shares their well-developed artistic vocabularies. Fire is a mighty force that affects nearly everyone’s consciousness on some level. For Mary Ellen Long, having grown up in southern California and living for the past 25 years in the mountains of southwest Colorado, fire has left an imprint on her psyche and its influence can be seen in many of her sculptures and collage works. Twice evacuated from her Missionary Ridge home and studio during the fire of 2002, Long had been thinking about fire in these forests for many years. On her walks through the tall pines, she would find evidence of a previous fire, which she later found out from a fire historian, had raged through the area in 1880. In “Missionary Muse,” Long’s elegant installation “Remnants” greets each viewer, a mobile of sorts that is comprised of hanging branches charred by fire and dried aspen leaves sewn in long strands alternating with a man-made green ribbon that looks like the forest made them. For this exhibit, she has created artworks using the burned natural elements – charred tree limbs and roots, sooty rocks, and ashen bark – that she gathered while walking through the 2002 burn area. She says of the work, “These pieces become the memory works and a type of exorcism for me – working out my fears, my anger and my sadness.” In her bookwork, “Buddha Incense (from the Mountain Series),” Long uses two rocks as bookends with a folded, accordion-like piece of paper spanning between them. The folded page is a dark, silky black on its lower half and meets a glowing orange upper band, defining a horizontal mountainous ridgeline backlit by a fiery sky. Meandering across what represents the blackened earth are the words, “Into the spiral whorls the storms of the Milky Way Buddha Incense in an empty world Black pit and light year Flame tongue of the dragon licks the sun.” Some of Long’s assemblage pieces incorporate photocopied topographic maps of Missionary Ridge giving us a hint that ‘place’ is important to her. She may be posing a metaphoric and metaphysical question, “Where do I stand in nature?” While Long uses actual objects from the Missionary Ridge burn area, Chet Anderson takes a documentary approach with his intricately toned black and white photographs. Shot with a large format camera, the 4” by 5” negatives produce detailed images and subtle tonal variations showing abundant new growth and dead tall trees. Anderson waited until 2004 to go into the forest to photograph. With a background in forest ecology, Anderson knows that a burnt forest means two things: destruction and renewal. He held off his visits in order to witness the new life that is always apparent the first years after a fire. Many of his untitled images have a mesmerizing quality: the strong verticality of photographing in a forest lends itself to a feeling of disorientation. Add to that the presence of delicate small plants juxtaposed with branchless blackened trees and a sense of mystery is created. Anderson responds, “Whenever there’s a transition, it’s a strange feeling . . . the transition between death and life and life and death contributes to the mysterious part.” A self-taught photographer, Anderson “got turned on over 50 years ago by Ansel Adams, primarily because of his conservation outlook in his photography.” In a similar vein of consciousness, Anderson’s life has been spent paying attention to nature. The photographer is attracted to strong forms, textures, and heightened contrasts between light and dark shades. His eye is drawn to the details of silky black bark peeling from trees, revealing its vulnerable bareness and capturing on film what seems like a very slow molting process. Anderson writes in his artist statement, “Commemorating an eventful fire is a simple way to celebrate life’s renewal and may serve as a reminder to be a bit gentler in our environmental relationships, and also how inseparable are our lifestyles to the vagaries of “natural” phenomenon.” • “Missionary Muse” is on display in the Arts Library at the Durango Arts Center through August.

|