| ||

Wandering into contemporary art

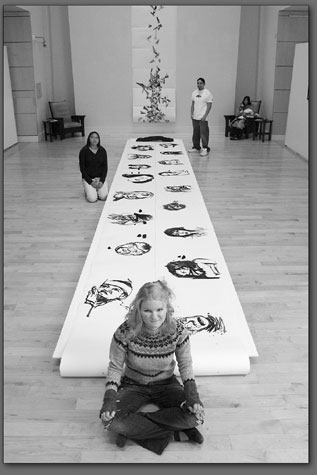

by Jules Masterjohn Appreciating contemporary art can be challenging. One can look to the mid-20th Century for a foothold on what happened to bring about the arrival of radically new art forms. In a post-World War II America, visual art entered a time in which its definitions and forms were modified and expanded, confusing audiences and the art market. This innovative and experimental period in American art forever altered our culture’s understanding of the purpose of art and the role of artists within society. By the early 1970s, some artists were fusing painting, sculpture, theater and video to forge a new expression, installation art. Over the last 35 years, this contemporary form has taken hold and grown deep and broad roots into the bedrock of contemporary art. An “installation” is generally understood to be an arrangement of objects in an ensemble or environment, with some works also created with a specific location in mind. This is referred to as “site-specific installation.” The viewer has the experience of being surrounded by an environment, enveloped in an artist’s intention. Durango is currently home to a temporary site-specific installation, “Borderline,” created by New Mexico-based artist Michael P. Berman in collaboration with three Fort Lewis College art students. Installed at the Center of Southwest Studies, “Borderline” is a stunning arrangement of paper, photographs and charcoal drawings elegantly centered on the floor and north wall of the gallery’s cathedral-like space. Upon walking into the gallery, I was aware of the sweeping scope of this work. Berman spends days, sometimes weeks “wandering” with his camera in the border-region deserts in New Mexico. The desert’s vastness is felt here with a palpable sense of where earth meets sky. A strong, linear black and white element runs through the piece, reminding me of harsh desert shadows, a visual experience reduced to the simplest matters of light and dark. In the center of the gallery, a low table structure hovers inches off the floor, on it a series of larger-than-life-sized human portraits. The succession of faces creates a rhythm that pulls my gaze over the paper’s surface to the back wall. Discarded pieces of natural charcoal used to draw the portraits quietly lie on the paper, their job done. A single line of typed text runs the paper’s length. On the end of the paper, near the wall, rests a large, burnt tree limb, a silky black segment of naturally made charcoal, a remnant of the Missionary Ridge Fire. Here, “Borderline” takes to the wall. Hanging from ceiling to floor nearly 25 feet is another lengthy piece of paper used as the backdrop for mounted segments of Berman’s black and white photographs of desert environments. The triangularly shaped photographs tumble down the center of the paper and pile up near the bottom, a few feet from the burnt tree limb. Standing back from the piece, my gaze rocks back and forth, up the wall and then down across the floor. Moving closer, I get to appreciate the nuances in “Borderline,” the subtleties in drawing and the varying facial expressions in the portraits drawn by students Mihdi “Butch” Bathke, Myra Johnson and Kristen Smith. Also readable, upon closer inspection, is a line of text that is taken from research on creativity by David Bohm, a notable Quantum physicist. Berman explains, “The quote is saying, if you want to destroy creativity, give someone positive reinforcement. When an ape makes a painting it forgoes food, sex, etc., but if you gave the ape reinforcement, it will loose that creative urge.” Taking this research to heart, Berman chose to show the “younger artists” the possibilities within the installation and then “let them go.” A nationally known photographer and artist, Berman made his way to Durango through Fort Lewis College art professor Chad Colby, who has known Berman for years. Colby, with the endorsement of the college, invited Berman to create an installation and suggested collaborating with art students as part of Berman’s offering. Colby felt that the students would gain valuable experience working with a professional artist on an installation in a “first-rate gallery” setting. Colby contacted Kristen Smith, president of the art students club, and soon the collaborative team of Smith, Bathke, and Johnson was ready to work. The team met only briefly with Berman to discuss the piece, though the students had been introduced to Berman’s background, creative process and artistic ideas from a presentation he gave at the art department. Berman and the three “young artists” went together to collect charred wood for the installation. He set the component pieces and then left Durango, and the team to its own artistic devices. With little direction from Berman, Smith became the team’s rallying point. Drawing is a love of hers, so she had the idea to draw figures in charcoal as their collaborative element. After some discussion, Smith, Bathke and Johnson agreed that their contribution to “Borderline” would be charcoal portraits of Latino film stars. Jeanne Brako, the director and curator for the center, chuckled as she told me that she was “shocked” to see the inclusion of human faces into the installation. “Michael (Berman) talks so much about going to places where there are no people that we were just surprised by the addition. And we love it.” Berman’s perspective on installation art is one of action and interaction. Berman offered, “I think of the word ‘installation’ as a verb and a process rather than as a noun, which is more of an object. With this perspective, I like to get to a space and see what unfolds, what takes shape in the gallery. It is my strong bias. I wanted to introduce this to the younger artists: instead of working in the gallery to fulfill a previously conceived idea, you could start with materials and see where they lead you.” “Borderline” is on display through Dec. 15. The Center of Southwest Studies gallery hours are Monday-Friday, 1-4 p.m. Berman’s work can be viewed at www.fragmentedimages.com. •

|