|

|

||||

|

Living with the monster Durangoans come to terms with multiple sclerosis SideStory: 471 miles for MS: Colorado Trail journey draws to an end

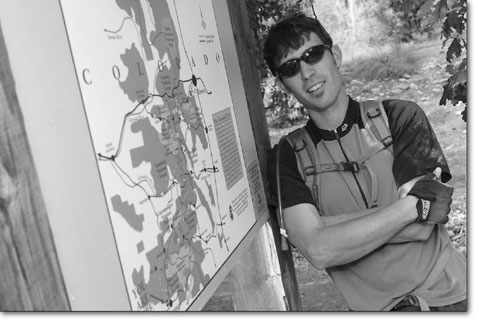

by Will Sands Ian Altman began noticing problems eight years ago. “When I was 24 years old and just finishing up at Fort Lewis College, I started having symptoms,” he said. “Numbness started in my legs and moved up into my fingers. Over time, it became total numbness from the neck down.” After several differing diagnoses, an MRI and a lot of time in the dark, Altman was informed that he had multiple sclerosis. Today, the disease has done little to slow him down. Altman is director of fine arts and rock climbing at Colorado Timberline Academy. He recently returned from a climbing trip to the Yosemite Valley, has summited the challenging Cerro Fitzroy in Patagonia and plans to ride the entirety of the grueling, 79-mile Molas Pass-to-Durango stretch of the Colorado Trail this Sunday in honor of CT4MS (see sidebar). And Altman is not alone. He is one of a growing number of Southwest Colorado residents not only coping with the ravages of MS but doing it in style. “So many people have learned to deal with the disability and gone way beyond their previous limitations,” Altman said. “I’m climbing better now than at any time in my life because I’ve learned to deal with MS.” Still, MS is a disease cloaked in mystery. “There is no cause, no cure and no treatment,” said Durango’s Jeannine Pope, who was diagnosed with the disease 15 years ago and is currently president of the Southwest Colorado MS Society. MS is a chronic and unpredictable disorder of the central nervous system and thought to be an autoimmune condition. MS takes place when white blood cells attack myelin, the sheathing around nerve fibers, and replace the protective coating with scar tissue. The disease manifests itself in a variety of ways. One person may experience abnormal fatigue. Another might have trouble with balance and coordination. Still another may experience cognitive issues or blurred vision. “MS is a disease of the brain and spinal chord,” Pope said. “Wherever the damage ends up dictates where your symptoms appear, and really no two people have the same disease.”

MS targets twice as many women as men and is most common among Caucasians. It is also especially dominant in northern latitudes. Durango, the Western Slope and all of Colorado are considered a MS hot spot. One in every 580 Coloradoans has the disease. In Southern states, it affects only one in 10,000. Plus, the number just jumped in Colorado courtesy of improved diagnostics. Only four months ago, one in every 625 Coloradoans officially had the disease. “A lot of the change is due to better diagnostics,” said Priscilla Mangnall, of the Western Slope branch of the National MS Society. “Our statistics come from the people we know about. But we do know there are a lot more people out there.” The one thing all people who suffer from MS have in common is that the disease worsens. If completely untreated, it can be totally debilitating. “It’s a progressive disease,” Pope said. “Drugs help stop the progression or at least slow it down. And that’s really the only chance we have for a better quality of life.” Mangnall added, “Really the biggest hope has come in the last 10 years with the new MS drugs. They keep you from getting flare-ups, and every time you get a flare-up, you get permanent damage.” Altman concurred. Immediately after his diagnosis, he opted for alternative and homeopathic remedies and was able to manage the symptoms. A year later, things got progressively worse. He started noticing problems with his vision, had trouble walking and began experiencing vertigo. After a climbing accident, two broken heels, three months in a wheelchair and two leg casts, he decided to give one of the drug treatments a chance. “Right when I started the injections, it really started to take effect,” Altman said. “Even with these big moon boot casts on my feet, I could walk better than without the medicine. It was obvious that it was having a big impact.” Altman still takes Copaxone and is a member of Team Copaxone, a group of athletes who are overcoming the impacts of the disease. Along with Copaxone, the drugs Avonex and Betaseron are being used to successfully treat the progression of the disease. However, more than half of people with MS are unable to use the costly therapy or choose not to. “I got to see the other side of not being on medicine,” Altman said. “The Copaxone immediately slowed the progress and made it possible for me to go back and do these things and climb in areas where I never imagined I’d ever be.” Mangnall credited Altman and others for coming to terms with MS and learning to work with it. “You’re not going to die with MS, so you just have to learn to live with it,” she said. Even with the advent of drugs, Altman said that living with MS is definitely a roller coaster ride. While he is on the top of his game right now, the monster, or MSter, is never far away. “The MSter’s always there,” Altman concluded. “But I wouldn’t have gone to South America without MS. I wouldn’t be climbing as hard as I am now. I wouldn’t even consider doing this ride on Saturday. I consider it a gift, really.” •

|

In this week's issue...

- May 15, 2025

- End of the trail

Despite tariff pause, Colorado bike company can’t hang on through supply chain chaos

- May 8, 2025

- Shared pain

Dismal trend highlights need to cut usage in Upper Basin, too

- April 24, 2025

- A tale of two bills

Nuclear gets all the hype, but optimizing infrastructure will have bigger impact