|

Silverton printer dedicates himself to older processes

|

|

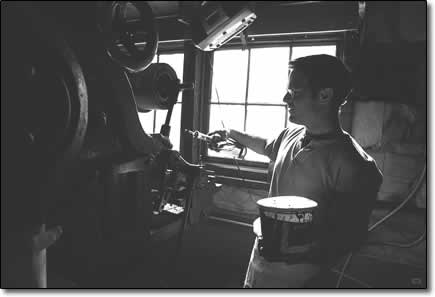

Printmaker Dan Garner uses water to clean the ink from "Thug," a 1920 Dye Stamping Press, in his shop in Silverton. Garner, who owns three vintage presses, uses the 3-ton Thug for printing engravings, or intaglio, prints./Photo by Jared Boyd.

|

by Shawna Bethell

"There was this old guy in Vermont. He was a gunsmith, a carpenter. I went to talk to him once with a friend of mine.

His hands were like roots of a tree. 'Do something with your hands, boys,' is what he told us. My friend was a

writer, and I was a printer."

Dan Garner, owner of Bird in Hand Letter Press, is a printer and an artist. He also does copper engraving and wood

engraving. And, on the occasional evening, he plays the fiddle with local musicians. Someone interested in having a

wedding invitation printed, or wood blocks engraved for book plates, or posters printed on a letter press (the kind

where each letter is hand set, backwards and upside down, like you used to see in the movies) can find Dan in an old

shed in Silverton. Classical music will be emanating from the radio suspended from the ceiling. It will be

inordinately loud as to be heard over the rumble of "Thug," a 1920 Dye Stamping Press, or the quieter rhythms of the

1906 Chandler and Price Platen Press. Chickens, New Hampshire reds (a snazzy little chicken Dan will say) and buff

orpingtons will strut through the door occasionally to check on what used to be their coop before Thug moved in. And

in the corner, honored by a glint of early morning sun, will be a 1961 BMW R695 motorcycle, which Dan will sit on,

wipe the dust off of and say, "The design didn't change much from the World War II models.

"Actually, one of my mentors and colleagues, Brian Cohen, of Putney, Vt., had one. I guess it's kind of like honoring

a predecessor."

Garner was teaching intaglio printmaking and hand engraving for Cohen at a print makers' cooperative in Bellows

Falls, Vt. (intaglio being the process where a design is carved into a solid material such as stone or wood, then

inked and pressed onto paper to create the finished product) when he first saw a letter press, an iron mammoth from

an era past. It was love at first sight and a natural next step for Garner.

"They are dying arts," says Garner of engraving and letter press. "There are maybe 20 or 30 people in the entire U.S.

who are doing it. These presses are being torn apart and sold for scrap metal. It's terribly sad." Sadder still, says

Garner, is the loss of knowledge. There is only one company that still supplies letter press operators, and they are

older folks.

"You call them and they want to talk and give advice," Garner says. "They connect you to other letter press people."

Garner owns three presses that he has found by just keeping his ears and eyes open. Thug, the 1920 vintage 3-ton

press, is the one he uses for printing engravings or intaglio prints.

"On a good day, I can run 1,000 sheets per hour," says Garner. This means that after the press is set up, i.e., hand

mixing the paint, adjusting the pressure, tweaking the alignment of the plate, etc., Garner can hand feed 1,000

sheets of paper into the press to have his intricately engraved design stamped on the sheet. It is a temperamental

process, but one that he loves.

With the large press running you can barely hear Garner, awe in his voice, "the ink roller crosses the plate with

just the right pressure. It can't be so hard as to smush the ink into the plate, or so light it doesn't allow for the

plate to be fully inked. It just brushes across with perfect pressure so the design in the plate is inked and can be

cleanly pressed onto the paper."

Garner engraves the copper and wood plates he uses on the press by hand. This was initially his first love.

|

|

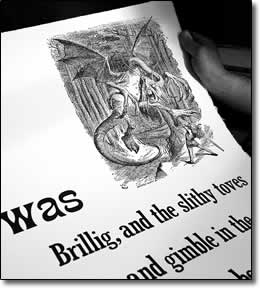

Garner used a combination of modern technology and historic process to make this poster./Photo by Jared Boyd.

|

Garner engraves the copper and wood plates he uses on the press by hand. This was initially his first love.

"I was in college at Middlebury," remembers Garner, "but ready to drop out. The English program I was working in

seemed stuffy and constricted. It seemed pretty futile. I had a job on a schooner which sounded a lot more exciting.

Then I took a winter course in engraving."

The course changed his college career. He eventually did leave printmaking and sailed for three years in Europe and

the Pacific. He settled in Hawaii, where he worked in horticulture propagating lotus and water lilies for estate

ponds. But he felt an emptiness and knew he needed to get back to his artwork.

From Hawaii, Garner started traveling and found himself in Silverton looking for old presses. He ran into Bev Rich,

of the San Juan County Historical Society, at the museum and took her card. The fine type set had been done on a

letter press.

"Where'd you get this?" he asked. Rich led Garner to Fritz Klinke, who has been printing in Silverton for several

years, and Klinke took Garner under his wing. Two years later, Garner started Bird in Hand Letter Press.

"I love it because it's tangible," says Garner of his art. "You can feel it. Feel the weight of the type set in your

hands, feel the texture of the paper. It's a luxury to work with beautiful paper, to mix the ink by hand. From

inception through completion, you know it is part of some great process. You know that someone somewhere had to put

time and talent and a lot of fussy energy into it."

And that, more than likely, is why it is a dying art. According to Garner's theory, our society has surrounded itself

with things that are quickly and easily obtained. This process is not quick. There is a lot of time and a lot of

patience involved.

"I feel an affinity with a different era," says Garner after a conversation about tapestries and other arts being

kept alive primarily by museums and historical societies. "There was a different concept of time, then. It was valued

in a different way."

|

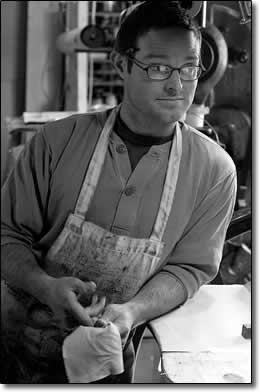

| Garner cleans the ink from his hands at his shop, where he uses turn-of-the-century printing machines to make art./ Photo by Jared Boyd |

After a pause, Garner leans an elbow on the 1906 Platen press, the one with a large circular ink plate and three

rollers, and folds his ink-stained hands. "It used to be known as one of the Black Arts," he says.

Garner goes on to explain that because of the many specifics entailed in print making, few people knew the process,

and it became somewhat secretive, a bit mysterious. Printing also was an information source when much political,

religious and pornographic information was controlled. Therefore, it gained a dark reputation.

Today, Garner is working with digital technology in an effort to blend his artistic dream with economic viability. He

can have a designer put something together on a computer program, send the file out and have a negative made, then

make a plastic plate to use for printing. This allows him to stay current with modern design tastes, and it is a

quicker process. It does not mean he is leaving behind the intricacies of hand engraving, it only means he is

blending the old with the new to remain commercially competitive. "I'm too fascinated with the older processes," says

Garner. "I mean we have (Albrecht) Durers lying around and Rembrandts lying around, but the methods they used we are

losing. Holding onto these things helps us to understand who these people were and what they were doing. It keeps us

connected, somehow."

|