A look at ‘The Art and Crimes of Ron English’

|

|

One of Ron English's more infamous works, "Mc Super Sized," looks down on the residents of New York City. A film on English's exploits as a guerrilla artist, whereby he commandeers corporate billboards and superimposes his work and subversive message on top, is being screened at the Durango Film Festival. "The Art and Crimes of Ron English" shows at the Abbey Theatre on Friday at 7 p.m./Courtesy photo/Courtesy photo

|

Big city street art, the likes of which we rarely get to see in Durango, is confronting our

polite community in the form of a documentary film, "The Art and Crimes of Ron English," being screened at the

Durango Film Festival this week. An informative look into the high-quality mature guerrilla art of one artist, this

film is a must-see for anyone who wonders how the power of art can affect change in our culture.

The film introduces the audience to the contemporary artist, Ron English, through his most public and controversial

works, his "illegal billboards," wall-sized, slick-looking paintings on paper that lampoon corporate America and the

messages and products they sell. Called "culture jamming," English's art co-opts the slogans, logos and "looks" of

major corporate billboard advertising as a means of subverting the corporation's message instead of sustaining it.

Nevermind that English is covering over existing ads and "stealing" the advertising space paid for by big business.

The fact that he is committing a second-degree felony, criminal mischief, does not alter English's commitment and

passion, being an outlaw is a badge of honor to him. "I damn sure didn't make the rules, I damn sure won't live by

them," he says in the film.

Apparently his DNA is coded with the criminal gene, for in the film he admits to shaking the same family tree as

Bonnie Parker, of the bank-heisting team of Bonnie and Clyde. To some, the artist's "crimes" may be seen as moral

actions taken to confront a world of corporate domination where a young person doesn't know the difference between a

peace sign and a Mercedes-Benz logo. One supporter in the film offers, "He is like Robin Hood, stealing from big

corporations and giving it back to the people."

The artist has appropriated the images of Joe Camel and Ronald McDonald and has worked his English on the Apple

Computer's slogan, "Think Different," by placing the face of Charles Manson next to the corporate tag. And he has

taken stabs at the current U.S. administration for its blurring of the lines between church and state. The borrowing

of corporate advertising themes has required that he retain a lawyer to defend him from corporate lawsuits; English

has been unsuccessfully sued by Disney and King Features, the owners of the Charlie Brown characters, to name just a

few. Despite the assaults on the Constitution these days, at least in English's case, the First Amendment appears to

be alive and well. Thankfully, so is English, though he has received threats to his life from factions of the

Christian right. So much for turning the other cheek. Perhaps they aren't comfortable about freedom of speech in a

world where one might encounter a large billboard stating, "One God, One Party," in bold letters along with the

endorsement, "Republicans for a Dissent Free Theocracy." Another of English's billboards that exposes the affiliation

of our government and fundamentalist Christianity reads, "Bush + Cheney: It's Armageddon America."

So how does a nice boy raised in the Midwest turn into the great grandfather of "culture jammers?" It wasn't until he

became a father that English took a serious interest in the very specific ways in which corporations target children,

using cartoon characters like Joe Camel and Ronald McDonald, to increase their market share. He launched a series of

"illegal billboards" depicting baby Joe and Josephine Camel with cancer sticks dangling from their young lips. It's

difficult to know for certain, and RJ Reynolds isn't telling, whether English's aesthetic assault had anything to do

with the company abandoning the Joe Camel advertising campaign. English believes it did and hopes his "subvertizing"

will fire people up to the point of letting corporations know how they feel about product lies and manipulative

tactics used to sell products.

English is not alone in his suspicion of corporations and their advertising techniques. Morgan Spurlock, producer and

director of the documentary film, "Super Size Me," encountered English and his crew on a New York City street one

afternoon, pasting up one of English's billboards, "Mc Super Sized," picturing a puffy and fat child-like Ronald

McDonald. As well as making billboards that lampooned McDonalds, English had also created a series of oil paintings

on canvas depicting sinister-looking child clowns, reminiscent of Ronald juniors, confronting the viewer with

uncomfortably provocative stares, as if these youngsters had lost their innocence and are children only in

appearance. After reviewing the McDonald's-inspired series, Spurlock offered English's paintings a cameo appearance

in the film.

|

|

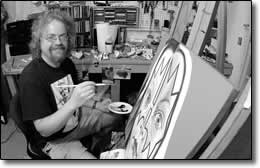

New York artist Ron English creates in his Manhattan studio./Courtesy photo

|

English is not alone in his suspicion of corporations and their advertising techniques. Morgan Spurlock, producer and

director of the documentary film, "Super Size Me," encountered English and his crew on a New York City street one

afternoon, pasting up one of English's billboards, "Mc Super Sized," picturing a puffy and fat child-like Ronald

McDonald. As well as making billboards that lampooned McDonalds, English had also created a series of oil paintings

on canvas depicting sinister-looking child clowns, reminiscent of Ronald juniors, confronting the viewer with

uncomfortably provocative stares, as if these youngsters had lost their innocence and are children only in

appearance. After reviewing the McDonald's-inspired series, Spurlock offered English's paintings a cameo appearance

in the film.

Today, numerous galleries on both coasts represent English, and his paintings fetch handsome prices with an audience

of "intellectuals" who appreciate his substantial talent as a painter, his witty and sometimes humorous visual

allegories, as well as his astute critique of American popular culture.

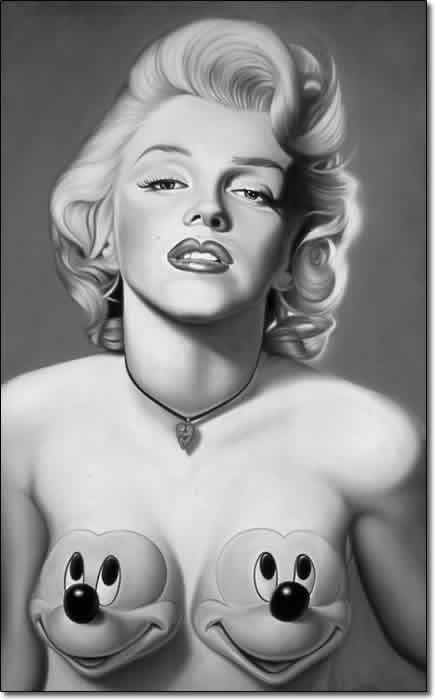

In his painting, "Marilyn," a seductive Marilyn Monroe, eyes at half-mast, seemingly leans off the canvas into the

viewer's lap, with bright-eyed Mickey Mouse heads growing naturally from her breasts. An interesting juxtaposition of

images, the impetus for the painting came to English while he was caring for his child. "The first thing kids are

into is their mother's breast," he told me in a phone interview. "Marilyn was the first pop icon, the mother of pop

culture, and Mickey Mouse was printed on my kid's disposable diapers." Female breasts are a source of nurturing and

bonding between mother and child in most parts of the world; in this interpretation of American culture, the breast

is replaced by a cartoon character. Perhaps the painting symbolizes our humanity being coyly seduced from us and in

return, we are given a mass-marketed placebo: nothing of sustenance is coming from Mickey's nose.

Created in the hometown of Wall Street and influenced by the popular culture machine of Hollywood, English's art

boldly reflects his experience. "People who live in the mountains paint what they see, the mountains. I live in New

York City, which is a big magazine, so I paint what I see."

"The Art and Crimes of Ron English" will show at the Abbey Theatre on Fri., March 11, at 7 p.m. Ron English's

artwork can be viewed online at www.popoganda.com.

|

| The idea for English's painting “Marilyn” came to him while he was caring for his child. English replaced the breasts of Monroe, the “mother of pop culture,” with Mickey Mouse heads, which he found on his child's diapers./ Courtesy photo |

|