|

by Chef Boy Ari

A few weeks ago I encouraged you to

pluck zee nectar and relish the exquisite pleasures available at

the apex of the growing season. That was a fleeting moment of sweet

corn and peaches, of right here, right now, as we sipped from the

cream of summer.

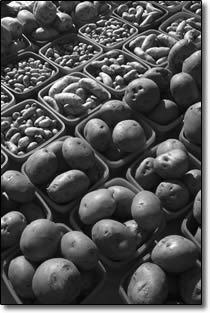

Now our hemisphere is

tilting away from the sun, and suddenly, every day is noticeably

shorter. The basil is turning brown in the cold nights, the apples

and leaves are blowing off the trees. It's time to prepare for

winter. On my stove right now, cooking slowly, there is plum

chutney, which I plan to serve with the wild game that I hope will

soon line my freezer. Meanwhile, the farmers are weary. Months of

constant movement and sleep deprivation have caught up, and you can

find them in their fields, gazing absently into the distance,

surrounded by great dirty piles of potatoes, onions, shallots,

beets, turnips, rutabaga and other bounty. Garlic hangs inside

barns, squash cures in the sun, and carrots stand ready for

digging. Now is the time when produce is cheap.

While the time for

plucking zee nectar has sadly passed, the task at hand is even more

important. This is the glue behind the glitter, the time to stash

the staples and do the work necessary to stock a year-round

pantry.

Sure, you can also buy

your food at the store when you need it. But when February rolls

around and you're paying $2 for a pound of potatoes, here's why:

you're paying for months worth of storage space for that food; you

are paying for shipping the food from that storage space, wherever

it may be, to the store. And in Februaryas opposed to nowpotatoes

are scarce, and the law of supply and demand conspires with these

other factors to jack up the price.

This discussion, of

course, is about more than money. A large stockpile of food

provides a unique brand of satisfaction, as does freedom from

always running to the store. And when you do go shopping, it's for

things like flour, oil, rice and chocolate. At meal time, you look

down at your plate and see ingredients that you recognize: venison

with homemade chutney next to potatoes, with a side of kale, which

was cooked with onions, garlic and maybe some morels from last

spring. How much you store depends on what kind of facilities you

have for frozen and cool storage. Owning a freezer is key.

Meanwhile, books abound with building instructions and diagrams for

root cellars, ranging from glorified holes in the ground to

wood-framed, stone-lined caves to railroad boxcars buried in the

sides of hills.

Those of us who don't

have hills or box cars or holes to dig might yet have an

unfinished, unheated basement or crawlspace, or an unheated garage

that stays cool all winter. Last year, it got so cold during a

January cold snap that I lost my squash and onions. Darn! But

everything else survived.

Those root cellar plans

are usually found in the same books that give instructions for

preserving your food. Another good source of information on food

preservation is Joy of

Cooking . And

while my words are admittedly a pale substitute for such dense

compendiums of information, I'll leave you with a few tips to

consider as you prowl the aisles of the farmer's market looking for

grub to stash: Don't wash food before storing it. Dampness invites

mold, and scrubbing can compromise the protective skin on some

veggies. Better to clean at the time of use.

Keep potatoes in a dark, cool, dry place, in ventilated bags, or

packed with straw in boxes. Store winter squash on shelves in a

cool, dark place. Check them periodically for mold, which you

should wipe off with a cloth dipped in vegetable oil. If mold

starts to take over a squashor anything elseget rid of it ASAP,

before it spreads.

Onions, garlic and shallotsaka the edible liliesdo well in mesh

bags hung in cool, dry, ventilated spaces. Leeks, the other edible

lily, are best frozen.

True connoisseurs of kale bide their time until after a frost,

which makes the leaves sweeter. Then they blanch the kale and

freeze it.

Ripe apples, pears and other fruits give off a gas called

ethylene, a ripening hormone. If you store ripe apples near

potatoes, the potatoes will sprout. Over-ripe fruit will quickly

cause neighboring fruit to ripenhence the clich`E9 about one bad

apple. Thus, sort your fruit carefully and store in a

well-ventilated place away from vulnerable foods.

Tomatoes can stay in the ground, covered, through light frosts.

But before a big one hits, I pull the whole plant, with tomatoes

attached, and hang it upside down near the apples, if available,

which will hopefully encourage the tomatoes to turn red. Even if

you don't have apples, most of the farmers I know agree that

hanging the plants whole is the best method for late-season tomato

ripening.

Now go and make some hay, so to speak, while the sun's still

shining! •

|