|

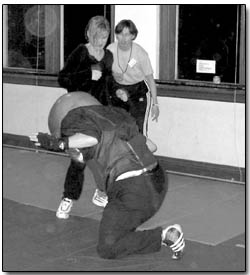

| Jennifer Reeder delivers

the crushing blow to her “assailant” during

graduation ceremonies for a Safe Passage workshop Saturday

night at the Smiley Building. |

No one has ever failed this class,”

Stephanie said.

“I’ll be the first,” I said.

It was 9 a.m. Saturday at a women’s self-defense class.

I’d been told that nine hours later I’d be in a

graduation ceremony where I would fight my way out of two assaults

– one standing and one on the floor. But in light of my

uncoordinated flailings in step aerobics, I wasn’t so

sure I’d be able to fight off a male assailant, no matter

how good the training.

But our three instructors from the Westminster-based Safe Passage

Workshops – Stephanie Pulhamus, Dennis Warren, and Stephanie’s

husband Dick – eased the 13 of us into the day slowly.

Stephanie explained that we would learn five to seven basic

moves for self-protection, because when adrenaline is pumping,

it is only possible to remember a few things. But because of

the simplicity of the moves, we would be able to remember them

years from now, she said. In fact, she told me about a former

Safe Passage student in her 70s who was attacked and sent her

assailant to the hospital with two broken insteps, a bruised

groin, a broken nose and a concussion. The woman told police

she couldn’t remember what had happened during the attack

except to mention she had taken a self-defense class about 10

years prior.

“It’s for all ages, all shapes and sizes, all health

levels,” Stephanie said. “It’s about using

whatever is available.”

This certainly seemed true of my classmates. Participants ranged

from two DHS seniors preparing for college to women working

through past traumatic experiences. One woman said for years

she had been in an abusive marriage, which had since ended.

Since then, she spent time running with her dog. But her dog

died last month, and without the feeling of safety the dog provided,

she hadn’t been able to run anymore. She was hoping the

class would give her the courage to resume her pastime.

Stephanie said many women who have experienced traumatic relationships

and assaults take the class, and although they won’t be

cured of their fear, they can make it their ally. Women can

learn to use fear to take action rather than freezing in an

assault. She said the class often is therapeutic because women

can “go back to the traumatic experience and put a different

ending on it.”

|

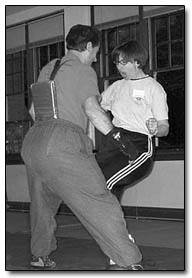

| Class instructor Stephanie Pulhamus uses

a knee to the groin in a self-protection exercise against

fellow instructor Dennis Warren./Photos by Bryan Fryklund. |

The class started preparing for attacks by learning some key

moves focused on the head and groin, since those are the body’s

two most vulnerable areas. Once the basics were established,

it was time to face the “muggers” – Dennis

and Dick in the patented armor and huge, padded helmet.

The first fight was verbal, because 70 percent of assaults

have a verbal component, Stephanie said. She pointed out that

many assaults can be avoided by being assertive and using a

loud voice to say things such as “Back off,” “I

don’t know this man,” and “No,” since

muggers and rapists often look for an easy target. However,

she stressed that while assertiveness could prevent a fight,

aggression, such as swearing or pointing, could escalate the

situation.

As women revisited past experiences while shouting down potential

attackers, the adrenaline pumped and tears flowed. Stephanie

held the participants’ hands as they walked out onto the

mat. As we’d been told, the “muggers” were

no longer our patient instructors, Dick and Dennis – they

were assholes.

When it was my turn on the mat, the mugger approached saying

something about my lips. I “anchored” in my protective

stance and yelled at him to back off, but he grabbed me, and

I had to knock him in the head and knee him in the groin and

head before he went down. I thought I was done, but I looked

up to see the other mugger coming at me. I was so charged with

adrenaline that I heard myself gesturing to the horizontal mugger

and yelling, “You want some of this?” I’d

crossed the line from assertive to aggressive and had to fight

my way out of a second assault.

Another round involved being attacked from behind. One participant

began crying upon entering the mat and being told to turn around.

“I can’t do it; I can’t have someone come

at me from behind,” she said through tears as one of the

muggers began circling and taunting her. But as we watched,

she turned and opened up a can of whoop ass on her assailant.

A similar scenario unfolded with the woman who hadn’t

been running since the death of her dog. As the mugger started

toward her, taunting her about her dog, she was clearly shaken

but fought him off like a tiger. And so went the rest of the

class: women overcoming fears and inspiring the rest of us.

According to Stephanie, the class was called “Women’s

Journey” because at the end of the day, participants have

taken a journey of self-discovery. And after watching women

reclaim their voices and rise above deep-seated fears, I was

inspired. Instead of feeling like a media spy, I was now a member

of a group on an emotional journey.

Perhaps one of the more difficult of the assaults was the simulated

rape, which placed women face up or down on the ground –

sleeping in a tent, lying on the beach. As a mugger pounced

on one of the high school girls, she flipped him over, beating

the hell out of him with one of my favorite moves, the “axe”

kick. When it came my turn, I don’t remember what my attacker

said, because the adrenaline was so strong that I couldn’t

even hear the fighting moves my classmates were yelling from

the sidelines. Face down, I planted a foot and used what my

mother always called “great child-bearing hips”

to toss him off. I lost a shoe, and my right knee now has a

bruise from a misplaced shot to the groin, but afterward, I

stood up safely to “look” around for more attackers,

“assess” his condition and run to the back of the

line to cheers of my classmates.

Afterward, as we watched a tape of the fights, there was more

cheering and encouragement. We felt united as we headed down

to “graduation,” to which friends and family were

invited. With the stage fright kicking in, I soon found myself

facing a sneering mugger. “Oh, I know you. You’re

that newspaper chick,” he snarled. I’m told I kicked

his ass.

After our final exercises, we formed a circle, while expressions

such as “I feel so connected to you all,” “I

don’t want to forget this” and “Thank you

all so much” were exchanged. When the circle was enlarged

to include family and friends, the woman whose dog had died

told the circle that because of the class, she was now able

to admit that she had been in a violent relationship.

“I’m so glad you’re writing this article,”

she’d said to me. “Women need to know about this.”

We knew Stephanie would ask if we wanted to say “yes”

or “no,” as we had several times throughout the

day. “Let’s say ‘Yes,’” someone

suggested. And the circle began to say yes to things like empowerment,

family and safety, while a sweaty Dennis piped in. “Yes

to Ibuprofen,” he said. n

For more information on Safe Passage,

go to www.safepassagenow.com.