|

Permacouple creates permaculture

written by Rachel Turiel

|

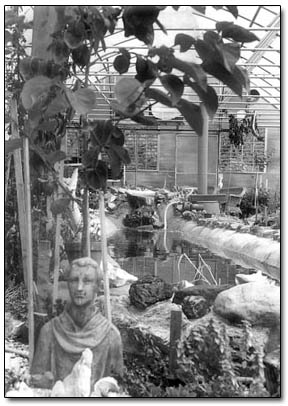

This 2,200-square foot

greenhouse at Oakhaven Permaculture Center, in La

Plata Canyon, is owned by Christie Berven and Tom

Riesing. The center,

which also includes outdoor gardens, is founded on

the idea of creating a sustainable lifestyle by working

with nature./Courtesy photo |

In other times and places, Tom Riesing crunched numbers

on Wall Street, and Christie Berven taught elementary

school. Since meeting in 1998, the two have been born

again and are zealots for their cause: soil, earthworms,

beet greens. Tom and Christie are the creators of Oakhaven

Permaculture Center, tucked into the gamble oak and lichen-covered

rocks at 8,700 feet off La Plata Canyon Road. The center

consists of a 2,200-square-foot greenhouse, outdoor gardens,

ponds, chickens and the ever watchful, astonished gazes

of its creators.

Christie Berven is high energy, exuberance and fire.

She pins you with her eyes, talking so fast you hope she

remembers to breathe. If she is fire, Tom is stone, quarried

from a deep, still place in the earth. His movements are

slow and calculated, as are the thoughts he expresses.

At the ages of 56 and 65, respectively, Christie and Tom

are starting a new sort of family, and certainly a new

sort of life.

In their comfortable solar and wood-heated home, the

three of us sit on pillows and I ask them the obvious:

“What exactly is permaculture?” It seems I’ve

asked the right question because Christie leaps up to

retrieve the multicolored educational banners she’s

been working on. “This is my winter work,”

she says, gesturing to the first of four banners she’s

spread across the woodstove.

Words and phrases scripted in bubble paint jump out at

me: “nematodes,” “building the soil

from the ground up,” “cooperation not competition,”

“connection.” Christie begins reading the

words out loud, and they somehow sound like a prayer for

the earth.

When Christie is done with her chant, Tom explains in

his practical way that permaculture is an agricultural

movement. “It‘s a term coined by Bill Mollison,

of Tasmania, based on the phrase ‘permanent agriculture,’

and has come to encompass the idea of a sustainable culture

and economy through working with nature,” he says.

Catching the cue, Christie bolts from her position on

the pillow and like Vanna White replaces the current banner

with a new one that bears the heading “Permaculture.”

It is a simple banner. A circle on the inside holds the

word “ethics,” and radiating out are four

phrases: “Care of the earth”; “Care

of all beings”; “Share the surplus”;

and “Aware of the limitations of the earth.”

We start with the phrase “Care of the earth.”

“Have you ever seen a mountain meadow?” Christie

asks as she hops to her feet and points north, where indeed,

the La Plata Mountains cradle many such meadows. “There

is a synergistic relationship happening. Some plants are

taller than others, and those that need that protection

from the sun will grow near the taller plants. No one

Rototills; no one fertilizes; the leaves die in the fall

and cover the ground, protecting it from the sun and adding

nutrients. We study these natural systems so we can care

for and benefit from the earth with similar ease and efficiency,

making use of the natural connections.”

“If the soil dies, we die,” Tom adds from

his pillow, legs crossed and back straight as a board.

“Building the soil is caring for the earth.”

The permaculturist believes in working with the natural

elements and features of the land to produce more with

less work. If you’ve got a cold spot in your house

or on your land, create a root cellar. If you’ve

got a slope, grow moisture-loving plants at the bottom

where rainwater will collect. If you’ve got oak

trees where you want a garden, trim their limbs and use

them as strong trellises upon which to grow grapes, hops

and other fruitful vines. Leave the serviceberry shrubs,

they fix nitrogen in the soil.

|

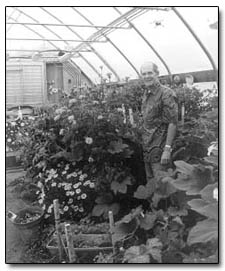

Tom Riesing,top, and Christie

Berven, bottom, pose among

the plants in their 2,200- square foot

greenhouse. The couple grows food

year-round in the greenhouse, using

rainwater and snowmelt to water the

plants. A pond, which collects heat

during the day, radiates heat at night

to keep the air above freezing./ Courtesy photos |

|

| |

Part of permaculture is harnessing natural, free energy

and recycling it before it degrades. In this spirit Tom

and Christie collect rainwater and snow on the north side

of their 72-foot greenhouse, channeling it inside the

greenhouse where it warms up in a large pond and is used

to water their plants. Heat also is sacred, and every

bit possible is collected, stored and rereleased. During

the day, fans suck the hottest air from the ceiling of

the greenhouse, funneling it into the soil where it blows

through 4,000 feet of slotted pipe in 150 yards of crushed

rock and sand and radiates back into the greenhouse at

night when the plants need it most.

Working too hard, against the flow of nature, is discouraged.

Any tilling that takes place is done by earthworms, chickens,

ants and snakes, all of which are welcome in the greenhouse

and outdoor garden spaces at Oakhaven. To prepare a new

bed in fall, they lay down cardboard “which the

earthworms love to eat,” then 6 inches of manure

and a thick layer of straw to top it off. Then the rains

and snow come, helping to break down the compost sandwich

and keep the worms hydrated. By spring, all the work is

done and they’re left with almost a foot of excellent

planting medium. Not only does tilling soil require unneeded

work, and often fossil fuels and money, it can break up

the roots of weeds, creating many more unwanted plants.

Tilling also destroys the network of fungal mycelia (mushroom

roots) which helps hold moisture in the soil and can have

a beneficial relationship with many roots of perennials.

And most of all, this is how the wild garden is built

by nature, from the ground up.

Tom talks about farming practices in California where

tremendous acres of strawberries are grown. “First

they spray the land with methyl bromide, killing everything.

Then they add fertilizer to support life.”

“It’s ass backwards!” Christie exclaims,

“They’re killing the insects, fungi and microscopic

organisms that naturally build and fertilize the soil.

Plus it’s too much work.”

A principle of permaculture design is to produce more

than what you put in, as well as save time, money and

space by having each element of your agricultural design

perform at least three functions. For Tom and Christie,

their greenhouse pond illustrates this ideal. In addition

to absorbing heat during the day and radiating it at night,

the 5,000-gallon tank holds water for plants and provides

humidity. “There’s so much moisture in here

in the morning you need an umbrella,” Christie says.

The bonus feature is the algae that grows in the pond;

it is scooped out and given to the plants as fertilizer.

After coming up to speed on the basics, the moment I’ve

been waiting for arrives. It’s time to visit the

greenhouse.

In the middle of winter this greenhouse, which is bigger

than the house I share with four adults, is like a temperate

coastal farm. Fragrant nicotiana flowers grow taller than

my head, plump figs

droop from limbs and a thigh-high mound of calendula with

sand dollar-sized blossoms seem to wave hello with their

yellow and orange heads.

“Fairies live here,” Christie announces matter-of-factly.

Tom plucks dill, arugula and beet greens for me to sample.

The greenhouse was built by Tom and Christie and a motley,

generous crew of FLC students and friends. It is heated

at night, though to no warmer than 40 degrees Fahrenheit.

Despite the chilly evening temperatures, tomatoes and

chili peppers are steadily turning from green to red.

Christie points out how the tomatoes grow in winter: low

to the ground to conserve heat. “The plants are

brilliant – they adapt!” she trills. Christie

recently cut back “a sea of medicinal borage flowers,”

though often when plants get crowded she stands back and

commands “you guys work it out.”

Although most of what they grow is for personal consumption,

Tom and Christie do sell or trade for some of their produce.

For example, last year they sold 85 pounds of pumpkins

to Durango Natural Foods, and occasionally they sell items

to the Kennebec Cafe, down the road.

As far as the future goes, Tom and Christie have big

plans. They’d like to grow mushrooms in part of

the greenhouse pond. They want to build a permaculture

center on their property for classes and workshops on

permaculture design, and sustainable building, eating

and living.

As the tour ends, I ask the ever expressive Christie

for any final words.

She grins and grabs Tom by the arm. “We’re

a permacouple, Tommy and me, and all we need is lovage.”

n

For more information on upcoming

classes at Oakhaven, call 259-5445.

|