|

Durango resident pushes climbing

envelope

written by Missy Votel

|

|

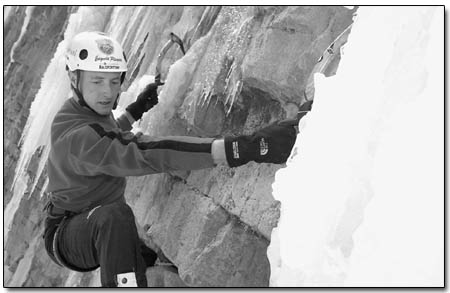

Jared Ogden dials in a mixed route in

Cascade Canyon, north of Durango, last week./Photo

by Dustin Bradford

|

You’re dangling a thousand feet in

the air on a platform barely the size of a twin bed with

a cold slab of granite for a headboard. You’re cold

and wet, and have been wearing the same clothes for days;

maybe weeks. You try to start your campstove for the daily

ration of ramen, but the sideways rain and wind thwart

your efforts. Darkness sets in, and your uncooperative

cracked, cold hands fumble the lighter. Too tired to retrieve

it, you give up and slink into your soggy sleeping bag.

Buffeted by sleet and wind, you attempt to shiver off

to sleep.

Welcome to the world of big-wall climbing – where

every day is a sufferfest and only the strong survive.

And being a smart ass never hurts either.

“Probably one of the best assets is being sarcastic,”

said Jared Ogden, world renowned big-wall martyr and free

climber. “In the middle of the worst situation,

you usually start cracking up, and that laughter is what

gets you through.”

That and something Ogden calls “retrospective pleasure.”

“A lot of times when I’m in the middle of

something awful, I think about the future and how nice

it’ll be when it’s done, and I can look back

and say, ‘Oh my gosh, look at what I’ve done.’”

|

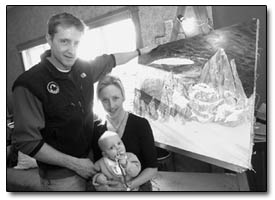

| Jared Odgen at home

with his wife, Kristin, and their 10-month-old son,

Tobin. Behind Ogden is a painting he is working on

of the Fitzroy Massif. The former Fort Lewis College

art student paints in his spare time./Photo by Dustin

Bradford |

Apparently the approach works. Since beginning his climbing

career about 13 years ago, the 31-year-old has pioneered

hundreds of first ascents, including a 4,000-foot assault

on the north face of Pakistan’s Nameless Tower in

1995 and a 1996 ascent of Baffin Island’s Polar

Sun Spire. He also won two gold medals in ice-climbing

at 1997’s X-Games and successfully summitted Pakistan’s

remote Shipton Spire. Along the way, he has shared portaledges

with the likes of Mark Synnott, Greg Child and the late

Alex Lowe. His feats have been immortalized in National

Geographic films and Outside magazine and landed him sponsorships

with La Sportiva and Black Diamond as well as a spot on

the prestigious North Face climbing team.

Perhaps Ogden’s greatest technical accomplishment

was his 1999 ascent of the nearly 6,000-foot northwest

face of Pakistan’s Great Trango Tower, believed

to be the biggest wall on Earth. The feat, which he undertook

with longtime climbing partner Synnott and Lowe, has been

called the greatest big-wall climb – and sufferfest

– ever. The face’s sheer size and 20,500-foot

summit, coupled with a perilous approach beneath a hulking

glacier that regularly sends down house-sized chunks of

rock and ice, had earned it a reputation as a “death

route.” However, after weathering 36 days of storms,

hypothermia, exhaustion, a mysterious intestinal illness,

a 50-foot fall, 1,000 pounds of gear, falling rock that

left Lowe unconscious and a 48-hour retreat in a tempest,

the team returned successful.

Despite

all this, the climber, who lives in Durango with wife,

Kristin, and 10-month-old son, Tobin, remains remarkably

grounded for an icon in a sport that in recent years has

seen a surge in popularity thanks to the commercialization

of extreme sports and the rise of reality television. Despite

all this, the climber, who lives in Durango with wife,

Kristin, and 10-month-old son, Tobin, remains remarkably

grounded for an icon in a sport that in recent years has

seen a surge in popularity thanks to the commercialization

of extreme sports and the rise of reality television.

Ogden admits it wasn’t always this way. After his

first taste of success in Pakistan, he said he was hungry

for more.

“I got back and started getting sponsorships, and

there was a story about it in the Alpine Journal,”

he said. “It gave me a taste of what I wanted, and

I wanted more.”

Ironically, it was the Trango expedition – which

arguably would be the coup de grace for any professional

climber – that proved to be Ogden’s big-wall

swan song.

“It was the media bonanza of the century,”

he said.

In addition to being filmed for an NBC special, the climb

was simulcast over the Internet on the now-defunct San

Francisco-based sports Web site, Quokka.com. Via daily

graphics, maps, photos and e-mails, armchair climbers

could make a virtual ascent alongside their heroes. And

although it was a plausible idea in concept, Ogden said

what sells to the masses doesn’t necessarily make

for a safe or successful climb.

“(Quokka) didn’t comprehend the amount of

work it would take for us to do what they wanted,”

he said. “Basically, we were taking orders from

this geek behind a desk in San Francisco.”

Added to this were the demands placed on the climbers

by North Face, which footed half the bill.

“Those trips cost a lot of money, and since North

Face was paying for half, they had a say, too,”

he said. “It snowballed out of control.”

According to Ogden, the hype and greed left such a bad

taste in his mouth that it affected his love for big-wall

climbing.

“It complicated things to the extent that it tainted

my experience,” he said. “It intruded on our

purpose. We were there to go climbing, to try to do something

for the sport, and all this media crap weighed us down.

“Pretty much since then I quit doing those big-wall

climbs.”

But this isn’t to say Ogden, at what was possibly

the height of his career, turned his back on the sport.

Rather, the experience, coupled with the responsibilities

of a new family, caused him to re-evaluate his climbing

career. In a sort of coming of age move, he decided he

was no longer going to climb for someone else, but only

for himself – and leave egos out of it.

“If things seem risky, I’m like ‘Forget

it; it’s not even worth it,’” he said.

“Climbing’s always been a very large priority.

But it’s not like I’m changing the world by

climbing. Having a family has rooted me more than anything

else I can think of.”

Ogden also said he has been humbled by the new generation

of climbers pushing the limits of the profession.

“The ’90s spawned a whole generation of extreme

athletes,” he said. “Before it was kind of

these fringe characters, and now there’s serious

people who train and are so much more talented. Things

are being climbed that are harder and sketchier and so

out there that it’s a little incomprehensible.”

And with the higher stakes comes more money.

“Kids are getting paid more than I do,” he

said. “I’m over the hill, some people would

say.”

But a look at Ogden’s recent endeavors shows he

is still very much on the hill. Recent expeditions include

a 2000 trip to Mount Jannu in Nepal, where Odgen, Synott

and Kevin Thaw were beaten back by 10 feet of fresh snow

and massive Himalayan avalanches. In 2001, he and Synott

summitted Alaska’s Moose’s Tooth, only to

get lost in a storm and nearly die on the descent. July

of 2002 was spent in Tibet, and December of 2002 was spent

in Patagonia, where Ogden and fellow Colorado climber

Topher Donahue put up two new routes.

Looking ahead, he has three different trips in the works

(which one he takes will depend on sponsorship funding)

as well as this weekend’s Ouray Ice Festival. And

further in the distance, he has his eye on several more

unclimbed peaks – the lure of which proves too strong

for Ogden to resist.

“First ascents are my favorite,” he said.

“Climbing them is like total anarchy. And the cool

thing is that no one’s shown you the way. You are

making your own way and doing it the way you want. It

is total freedom.”

|