Schlarb, Maggie and son, Felix, at the finish line for the 2014 Ultra-Trail du Mont Blanc, in Chamonix. He came in fourth for the 103-mile, 31,000-foot elevation course, finishing in 21 hours and 39 minutes./Courtesy photo

Not your average schlarpen

Think you’re tough? Run a day – or six – through the desert in this guy’s shoes

by Joy Martin

Two weekends ago, Jason Schlarb was in the San Juan Mountains skiing wind-scoured snow along the Hardrock 100 course. This weekend, he’s headed halfway around the world to run 156 miles across the blistering sands of the Sahara Desert.

JustthefactsWhat: “Kissing the Rock,” a documentary about the Hardrock 100 by Matt Trappe, followed by Q&A. Fundraiser for DHS and FLC Cross Country |

Despite the gusto behind these Herculean efforts, 37-year-old Schlarb is no weekend warrior. This is a mere snapshot of the life of one of Durango’s full-time professional athletes. Swap the ice axe for a snake bite kit and replace lynx sightings with camel interactions, and boom, you’ve got a modern-day explorer of the plushest degree.

Sponsored by Smartwool, Julbo and Black Diamond to name a few, Schlarb is paid to push his limits in all conditions and terrain. When he wins, he gets paid not just in prize money, but from his sponsors as well. In fact, ultrarunning can actually be quite lucrative, rumor has it.

However, at the same time he is working hard to perform at his best in a job he loves, he is working just as hard to carve out time with his stunning wife, Maggie, and rambunctious, turtle-obsessed, 5-year-old, Felix. What more could one ask for?

Those of you blessed with the enviable bliss of no FOMO might find this lifestyle intriguing, while others pout, “Great. Another professional athlete to make me feel like a chump.”

It really can be obnoxious being friends or spouses or Instagram followers of these folks. Social media alone creates a certain unfounded disdain for people who are simply doing exactly what you would be doing if someone was paying you to play hard outside. Every. Damned. Day.

But don’t un-follow them just because you’re jealous. Rather, choose to celebrate their accomplishments, find solidarity in their injuries, and discover inspiration for your next vacation, goal or role model.

Because at the core of each of Schlarb’s photos of craggy peaks and trails winding through dripping rainforests, is, if nothing else, a boy living his dream – at the cost of family time, ugly feet and the risky business of endurance athletics.

It’s not for everyone, but it works for him.

“It is absolutely the most amazing thing that’s happened to me,” says Schlarb of his third year getting paid to run full time. “Playing with my family outside when I want to, being there for Felix on an almost daily basis. I think that’s more rewarding than a six-car garage in Aspen.”

So maybe he’s gone for weeks at a time from his cabin in the woods east of Durango, gallivanting across New Zealand or running around Torres del Paine. But some of his “work trips” include packing the family up for Europe, like this summer, when Schlarb plans to run the Hardrock 100 and then head off for the 103-mile Ultra-Trail du Mont Blanc in Chamonix.

But first up, the Marathon de Sables (MdS) in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco on April 7, a new one for the seasoned ultrarunner.

Deemed “the toughest footrace on earth,” the 31st annual MdS draws more than 1,300 people from around the world to run six marathons in six days across sand dunes and salt flats in temperatures exceeding 120 degrees, all while carrying a week’s worth of food, sleeping bag, cooking gear and first aid kit (14 to 33 pounds of stuff). Every year, AC/DC’s “Highway to Hell” blasts at the startline, and at day’s end, runners converge at makeshift camps along the course to assess blisters, eat dehydrated food and drink rationed water.

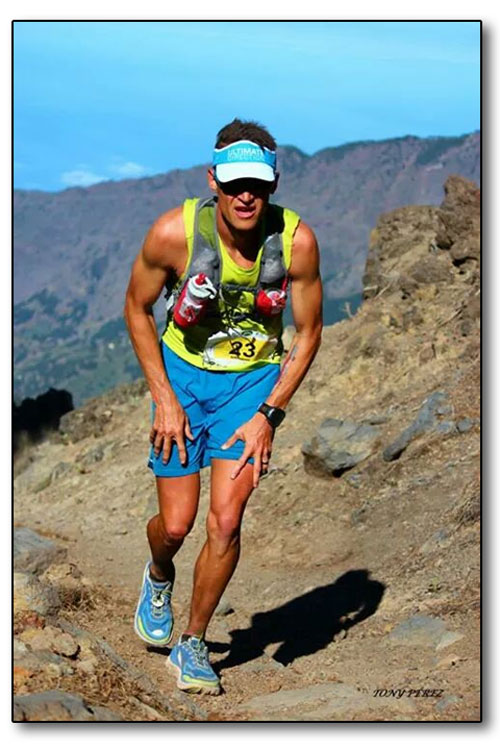

Schlarb at the 2015 Transvulcania Ultra in the Canary Islands./Photo by Tony Perez |

Three people have died in the 30 years of the race’s history, and one Italian guy got lost for 10 days after a sandstorm swept through (he survived by drinking bat blood and urine). So, everyone has to sign a form saying where they want their body sent in case they die. Runners pay a nearly $5,000 entry fee, not to mention the gear, medical tests and plane tickets.

But Schlarb won’t pay a dime because he’s running for Team I Run 4 Hope (learn more at hopesobright.org), which consists of five dudes – one from Italy, one from Mexico, one from Portugal and two from the United States – hand-selected by U.S. endurance runner and philanthropist Linda Sanders.

“Linda got our team together to bring awareness to ADHD,” says Schlarb. “She basically said, ‘Hey come do this race and we’ll pay for everything.’”

For Schlarb, the cause “really strikes home,” as his brother has struggled with ADHD and anxiety since his early teens.

“I’m excited to give back and play a little part in bringing some awareness on how to deal with ADHD,” says Schlarb. “Being a pro athlete is a pretty self-centered, self-driven job. Not really much giving back ... besides the inspiration factor.”

Sanders is hoping that this team of five ultra-stars will have what it takes to beat the Moroccan runners who seem to rule the podium on their home turf. Her vision is that by participating in

this sweltering adventure, people will relate the struggle of desert running to the struggles of ADHD.

"It's basically a starvation competition," says Schlarb on what it takes to win the MdS. "The less you bring, the faster you run. Aerobic, long, survival-mode running is one of my strengths as an athlete. I just need to keep moving efficiently."

Foot care is the most delicate challenge for MdS entrants, but Schlarb says he's good there.

"I've got way better than average feet," says Schlarb. "I've seen the carnage having run so many ultras, and I've figured out my weaknesses. The Altra toe box is perfect for me,” he says, referring to his brand of running shoes. “And I think my feet are pretty tough from skiing this winter."

Like, for instance, from the successful ski of the Hardrock 100 course two weekends ago.

"Trying to fit these two projects into a couple of weeks is really scary and challenging," says Schlarb. "It could not be a more diverse contrast."

But Schlarb does not only train physically for these feats; he's also mentally and emotionally prepared.

"Through the support of Maggie, I've learned that attitude mindset and positive energy are secret weapons," says Schlarb. "It's an art and skill and something that I really have been practicing."

When he’s in a race, Schlarb says he has a number of mantras, ranging from ad hoc to scripted to poetic. “Like, 'I do not care about anybody else in this race either in front of me or behind me. Be in the moment,’” he says. “And then once I'm in that moment … I just go through a lot of positive self-talk. I talk myself through fatigue. If my calf is sore, I send vital water, blood and oxygen to relax and stretch that particular muscle."

And when the going gets tough, Schlarb does the only thing that actually makes anyone feel better:

"I will make myself laugh out loud," he says. "The chemical reactions of both laughing and forcing a smile really help let go of pain.”

Then there’s the boredom, for which he does math games or mental gymnastics. And to keep from getting overwhelmed, he breaks things into bite-sized portions. “I basically just make it so that I'm not eating the whole cake, rather slice by slice."

These tricks of the trade are just teasers that aspiring runners can glean from one of Schlarb's coaching programs, which he runs with Maggie through their business, Schlarb Performance (www.schlarbperformance .com).

The last few decades have been spent collecting not only running styles but also coaching techniques from all over the world. The one-time high school state champ and nationally ranked track star with Montana State spent 10 years in the Air Force, where he ran for the All-Air Force and World Military teams.

"What most coaching doesn't do is address the whole person,” says Schlarb, who holds a MBA in business administration. "What about your family, friends and work? How do you balance goals between those aspects, without getting divorced or fired?"

In short, Schlarb is a go-getter, contrary to the traditional meaning of his last name. According to ancestry.com, “Schlarb” is said to stem from the German word “schlarpen,” which means "to shuffle along." In Germany, it's also a nickname for a negligent, sloppy person, a definition that couldn't be further from the truth for the Schlarbs of Durango. Talk about redefining your family's legacy. Here's to hope for all you Hookers, Mussolinis and Biebers out there.

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel