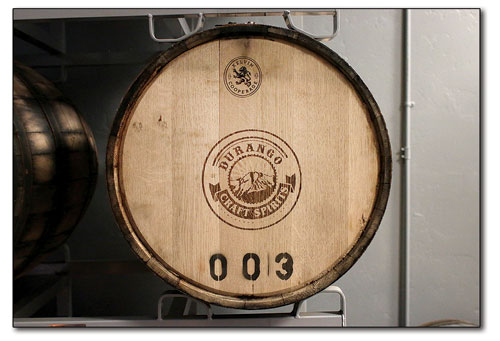

A barrel of unaged whiskey, aka Mayday Moonshine, awaits its transformation to bourbon inside charred oak at Durango Craft Spirits. The local distillery is among only 10 percent of its peers in Colorado that are grain to glass, i.e. everything from making the alcohol to bottling is done on site./Photo by Jennaye Derge

Raising a glass to the past

Durango Craft Spirits serves up shot of history with homegrown artisanal cocktails

by Missy Votel

Jim Croce may have mused about saving time in a bottle, but at Durango Craft Spirits, owner Michael McCardell has done just that.

Both of the spirits that are distilled on site – Soiled Doves Vodka and Mayday Moonshine – are nods to Durango’s somewhat tawdry past. Potent liquid reminders of the days when ladies of the evening (known then by the less flattering “soiled doves”) inhabited brothel row near what is now River City Hall and teetotallers forced bootleggers to seek the obscurity of the nearby mountains to ply their poison. Even Durango Craft Spirits’ cocktails are named after local lore. There’s one named for Durango’s first bootlegger, John Kellenberger, and another for Bessie Luck, one of Durango’s notorious madams. (Oh, and in case you’re already confused by the history lesson, it’s all detailed in the drink menu, which you can peruse with a cold beverage. Don’t worry, you won’t be quizzed.)

.jpg) |

Distilling for dummies:How to tell heads from tailsContrary to popular belief, distilling alcohol and making alcohol are two different things. All alcohol – whether it be beer, wine or whiskey – has its origins with the humble, single-celled organism known as yeast. Yeast takes the sugars from fruits and grains and breaks them down into carbon dioxide and alcohol. This process, known as fermentation, is the first step in making any spirit, and the only step where alcohol is actually made. In order to do this, a “mash” is made of grains (such as corn) and sugar. Then the yeast is added to do its magic. Once it’s done its job, the distiller is left with a “wash” – sort of a low-proof beer. In order to turn this into a spirit, distillation is necessary. Distillation separates chemicals in the wash by taking advantage of different boiling temperatures, essentially separaaating alcohol (ethanol) from water. Note, distillation does not produce alcohol; it only concentrates the alcohol already present. Thanks to its lower boiling point, it is easy to separate the ethanol from the water by heating the liquid and allowing the vapor to cool, rise and condense (think high school science class but on a much grander scale.) The resulting condensation is collected, where it ultimately ends up in your cocktail glass. Of course, this is an over-simplified explanation. There are several different types of alcohol and chemical compounds – known as “congeners” (remember this word, it will come up later) that can be extracted during the distilling process. Some are desirable in small quantities, while others (methanol, acetaldehyde) are discarded or set aside for future runs. Because the various alcohols and chemicals separate at different boiling points, there are several phases of each distillation run: foreshots, heads, hearts and tails. During the different phases of a run, taste and smell may vary considerably. Generally, only the “hearts” are kept for drinking. The tails are set aside to be distilled again in the future. For example, when making vodka, as many congeners are removed as possible because it is supposed to be a very pure, flavorless spirit. When making whiskey, however, congeners are desirable because they add flavor and complexity. One of the reasons whiskey is aged is to smooth out these flavorful, but somewhat harsh, congeners. Once distillation is complete, a spirit may be bottled or it may need to be aged. All spirits come out of the still crystal clear – spirits like whiskey only get their color from subsequent barrel aging. While smaller barrels yield a spicier, oak flavor, larger ones impart a mellower, more complex flavor. – Missy Votel |

“That was our philosophy from the beginning,” said McCardell, who opened the Main Avenue distillery with his wife, Amy, more than a year ago. “We wanted to tie it to Durango’s history – and Durango has such a rich history.”

Indeed, everything from the Victorian era tile work and the ornate wood bar to the historic Durango photos – including one of federal agents proudly standing beside a bootleggers’ bust – smack of history for those who like a little “local flavor” with their libations.

For McCardell, a 26-year resident of Durango, his history here is not nearly as salacious. Originally from the hops and barley fields of the Midwest, McCardell migrated out West and never looked back. It was here, more than a decade ago, that the spirit seeds were planted.

|

| Michael McCardell in his "devil's workshop."/Photo by Jennaye Derge |

Early on, McCardell – a printer by trade – gravitated to the craft beverage boom, befriending Ska co-founder Bill Graham and the rest of the crew. He recalls a day about 11 years ago when Graham came into the Ska tasting room with a brand new bottle of Jackelope Gin, produced by Ska’s sister company in Palisade, Peach Street Distillers. “We did a taste test with Bombay, and I was surprised at how much better the Jackalope was,” McCardell said.

With head slightly abuzz and wheels turning, McCardell got to work. He became a voracious connoisseur of Durango’s distilling past, reading books and picking brains of those in the know. But it wasn’t until a trip up County Road 250, to a faux Anasazi panel that masked an antique still (apparently, nothing was sacred during Prohibition) that he truly became intoxicated with the idea.

He decided to learn the ropes, going to three different schools teaching the alchemy of distilling and did an apprenticeship at Wood’s High Mountain Distillery, in Salida. The distillery is owned by brothers Lee and P.T. Woods, the latter of whom happens to be an FLC alum

“He taught me a few tricks,” McCardell said of P.T., who specializes in gin and whiskey.

With enough experience and cocktails under the belt – all in the name of “research,” mind you – McCardell began the arduous task of amassing equipment, finding a location (former home to the Backspace Theater which, incidentally, was the town’s first Safeway, built in 1939. More history!) renovating said space and, most importantly, churning out that liquid gold. Finally, after waiting more than two months for his federal distilled spirits permit, he and Amy threw open the doors at 1120 Main Ave. on Jan. 27, 2015.

“Amy thought it would be more fun to open a sandwich shop,” he said. “But eating is cheating.”

As an aside, if 11 years from seed-planting to door-opening seems like a painfully long time for the average entrepreneur, consider this. Making alcohol and distilling it is a very deliberate process, and McCardell – self admittedly – a very deliberate person.

“We’re kind of taking baby steps,” he said. “I want a really clean spirit. I make sure I take really big cuts.”

This, for the uninitiated, is distillery speak for separating the good stuff from the not-so-good stuff and has nothing to do with having his hand in the till. Suffice to say, McCardell is a little like Willy Wonka in his workshop while going over the dizzying array of vats, stills, dials, levers, pulleys, widgets, gadgets and even something inauspiciously called a “dephlamator.”

|

| Amy McCardell pours a stiff one for a moonshine mule at Durango Craft Spirits. Don't worry - this isn't greatgranddad's moonshine. Modern moonshine is exceptionally smooth and drinkable, like a white, unaged whiskey./Photo by Jennaye Derge |

“I call it my devil’s workshop,” he said.

Truth be told, McCardell insists it is not “rocket surgery” but nevertheless is apprehensive about giving out any trade secrets – this writer assured him they were safe with her. However, he is more than happy to offer complimentary tasters and chat about anything spirit – in a historical or cocktail sense – under the sun with customers.

And speaking of secrets, hold onto your lowballs, bourbon fans. Starting last November, McCardell began socking away his moonshine – which he described as unaged whiskey – in charred oak barrels. If all goes well, come New Year’s 2018, he’ll be rolling out Durango’s first craft-aged bourbon.

And for those who think just anyone can brew up a batch of smoky goodness, au contraire. According to McCardell, in order to call it a bourbon, there are certain rules that must be followed. For starters, all whiskey must be a minimum 51 percent corn and aged in new charred American oak barrels for at least two years. The final product cannot be more than 160 proof.

“I really want to produce a bourbon that’s ‘chewy,’ that you can sink your teeth into,” said McCardell, whose barrels were purposely extra-charred (a “4” on a scale 1-4). “I just want it to be really good.”

It is that persnickety attention to detail that carries over to his other offerings as well. Although the micro-distillery biz has taken off much likes its fermented cousins, beer and wine, the McCardells take great pride in being among only a handful of “grain-to-glass” operations. In other words, everything from the starter (a yeast-fermented mash not unlike beer) to the final, bottled product are made in-house. Even better, all their ingredients, from non-GMO corn from the Ute Mountain Tribe to good, old Durango tap water (for that “good Durango flavor”) are sourced in state.

“We’re real proud of that,” said McCardell.

Added Amy, “Only about 10 percent of distilleries in Colorado go grain to glass. Others buy bulk alcohol and put it in the still and blend it.”

Throw in some local O’Hara’s chokecherry jam, add ice, shake vigorously, and you’ve got the “total Durango cocktail,” she adds.

And so far, the recipe is working. Durango Craft Spirits now distributes across the state, from Grand Junction and Alamosa to Colorado Springs, Boulder and Denver.

But its spirit will always be in Durango. “It’s just fun, and it makes for a great story,” said McCardell. “Durango’s always been a drinking town.”

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel