Turning back time

Last month, I suggested in this newspaper that the only wristwatch a person ever needed to own was a vintage mechanical timepiece. Since that time, and perhaps because the gods were setting their watches by me, I received a first generation Pebble smartwatch for the holidays, purchased from an area thrift store for $25. I feel like such an anachronism.

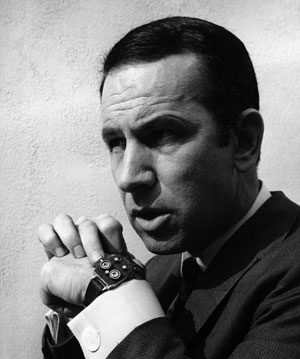

The Pebble is one of the early smartwatches that gained traction in the 2013 marketplace. Within a year, consumers purchased a million of them, but as is the case with many techy electronic gadgets, the Pebble line quickly updated its options with two newer, functionally and stylistically superior versions. The Pebble Round, for instance, actually looks like a normal watch, not like mine, a device brought forward from the era of Dick Tracy cartoons. Still, I feel lucky that in the two short years it took for the watch to wrap itself around me, I may have acquired my first smartwatch collectible without having to wait the usual quarter century.

The Pebble is one of the early smartwatches that gained traction in the 2013 marketplace. Within a year, consumers purchased a million of them, but as is the case with many techy electronic gadgets, the Pebble line quickly updated its options with two newer, functionally and stylistically superior versions. The Pebble Round, for instance, actually looks like a normal watch, not like mine, a device brought forward from the era of Dick Tracy cartoons. Still, I feel lucky that in the two short years it took for the watch to wrap itself around me, I may have acquired my first smartwatch collectible without having to wait the usual quarter century.

Think of me then as a time traveler, an omega rather than a beta tester, reporting on the performance of a relatively new product that people are already discarding. The watch was gifted to me in its original box and it didn’t reveal much wear, literally. When I opened the package, I admit to feeling the excitement and curiosity of trying to figure out how it worked. The manufacturer followed the usual web-savvy protocol by not producing a paper instruction manual, so I had to rely on the internet to figure out what to do with my new/used toy.

One thing I found out quickly is that smartwatches are designed to be fiddled with by the user. You don’t just strap the watch on in the morning and glance at it occasionally to check the hour. They lend themselves to button-pushing, wrist-shaking, selecting and unselecting. At the Pebble internet site I found hundreds of downloadable watch faces (with storage space in the watch for only eight), but I’ve been trying them out, switching from one to another, then back again, deleting the ones I don’t like and constantly peeking at the watch face. It’s addictive. If this continues I may be forced to wear my dumb watch once a week just to remember the time-honored protocol of stasis.

I’m still getting used to the unpredictable vibration that ripples my skin when the watch wants to tell me something of seeming importance. It vibrates when app updates are loaded, when incoming messages are received, and when my fitness app reminds me that I’ve been sitting on my ass too long. It’s a curious sensation, as if someone keeps nudging me and saying, “Hey!” I haven’t owned a smartwatch long enough to just ignore the notifications. When I wear my mechanical watch, it ticks if I hold it close to my ear, a rather understated attempt to soothe my outdated soul.

Since smartwatches use screens instead of dials, being able to read the watch under low-light conditions creates a new challenge. I have found which button to push that produces a backlit screen, or I can quickly snap my wrist for a few seconds of illumination, but inevitably I forget to put on my reading glasses and the watch flickers like a firefly before it dims and returns to an illegible hibernation. I could adjust the settings to increase the duration of the backlighting, but then the battery drains more quickly and I’m faced with the possibility of wearing a powerless piece of plastic.

The problem of squinting to read the hour is not exclusive to smartwatches. Early as 1917, a work force made up almost exclusively of women was employed to brush radioluminescent paint on the hands of clocks and watch dials so the timepieces would appear more visible. Unfortunately, those women licked the tips of their brushes in order to shape the bristles to a point. Instead of glowing smiles, they developed various radium-induced bone diseases and deformities.

Thankfully, by the 1930s this occupational hazard was eliminated with the introduction of phosphorescent paints. Comparatively, smartwatches are safer, unless users consider the Third World conflict materials that go into the production of all our electronics; the tin, tantalum and tungsten that have been referred to as the “new blood diamonds” that our insatiable desire for technologies has spawned. Screen resolution is today’s version of swallowing pixels instead of poisons.

I admit I’m part of the problem, an electronic gadget freak, always curious about the next innovation. I wouldn’t be surprised if the half-life of our culture’s obsession with all things electronic far exceeds the mere 1,600 years of radium-226, a drop in the pond long after my little Pebble smartwatch will have made its ripple and turned relic.

– David Feela

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel