Drying out

NCAR study predicts one-two punch for Southwest

by Allen Best

Peering through a window on a flight from Denver to Los Angeles, you first see the Rocky Mountains, rich with forests and snow. Then, for the majority of the trip you see aridity, the soft greens of sagebrush steppes dissolving to harsh pigments of the Mojave Desert until you get to the exurbs of L.A.

This is the American Southwest. Apart from its few rivers, it’s inherently dry, even parched – and, according to a new study conducted by scientists at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, getting drier as a result.

“A normal year in the Southwest is now drier than it once was,” Andreas Prein, NCAR researcher who led the study, said. The results were published last week in the journal Geophysical Research Letters. “If you have a drought nowadays, it will be more severe because our base state is drier.”

With less rain and higher temperatures, droughts will lengthen, researchers predict. “As temperatures increase, the ground becomes drier and the transition into drought happens more rapidly,” fellow NCAR scientist Greg Holland, said.

Water policy officials in both California and Colorado said the study provides further evidence of their challenges. Unlike other areas of North America, the Southwest walks a narrowing razor’s edge between supply and demand. This study finds evidence of less supply, even as climate models predict rapidly increasing temperatures – heat that will likely further reduce available water supplies.

Eric Kuhn, general manager of the Colorado River Water Conservation District, which is based in Glenwood Springs, echoed the emphasis on the twin drivers of drought: precipitation and heat. “Even if your precipitation goes up in winter months, like some of the studies have suggested, the overall net impacts of the increased warming in places like Lake Powell or at Lee’s Ferry will be less water,” he told Mountain Town News.

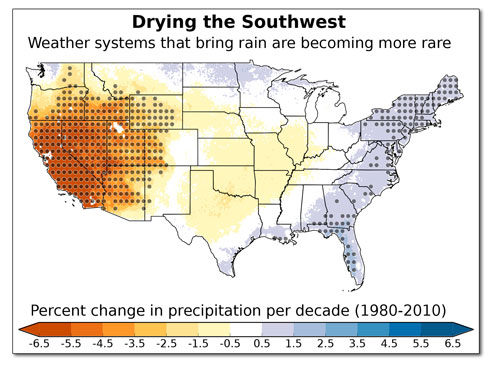

In the NCAR study, researchers analyzed 35 years of data to identify weather patterns. “The weather types that are becoming more rare are the ones that bring a lot of rain to the Southwest,” Prein said. “Those changes have a dramatic impact.”

Most wet weather to the Southwest involves low pressure centered in the North Pacific just off the coast of Washington, typically during the winter. Between 1979-2014, such low-pressure systems formed less frequently. In its place there has been persistent high pressure, the main driver of the devastating California drought.

These high-pressure belts can be found on both sides of the equator. They are created as hot air rises, moves poleward and then descends back to the surface. The sinking air causes generally drier conditions over the region and inhibits the development of rain-producing systems. Many of the world’s deserts, including the Sahara, are found in such regions, which typically lie around 30 degrees latitude.

Climate models have predicted that these zones will move farther poleward, or farther away from the equator. Still, the scientists pointedly declined to link the changed weather to longer-term human-caused climate change. Although it is a plausible explanation, linking modeled predictions to changes on the ground is challenging, they say.

The study also found an opposite, though smaller, effect in the Northeast, where wet weather patterns are increasing.

On the website ClimateProgress, blogger and MIT-trained physicist Joe Romm found the study’s refusal to link recent trends with climate change “overly cautious.” He underlined the potential for megadroughts, perhaps worse than the decades-long droughts in the 12th and 13th centuries.

Romm also warned of a future with higher temperatures and less precipitation. “If a region gets hit by both of those, it will suffer an unusually extreme drought, such as we’ve seen in California in the last few years, or Australia in the previous decade,” he wrote.

From his office along the Colorado River, Kuhn said the study he would like to see is one that paints the big picture: higher temperatures, reduced rain, the increased need of crop irrigation, plus the effect of reduced precipitation and higher temperatures on natural landscapes. “Nobody has put it all together,” he said.

In the Colorado River, about 75 percent of the water comes from snowmelt. But rainfall matters greatly as well. It also matters to how much agricultural crops must be irrigated, said Kuhn. “If the temperatures keep going up, we have problems.”

If it rains less in southern California, then the 18 million residents will rely more heavily on Colorado River reservoirs, especially Mead and Powell.

Much of the water stored in those reservoirs now gets used by farmers in Arizona and California. In the future, said Kuhn, those states will expand their transfer of water used for economically marginal crops to cities. This has been done through programs in which farmers are paid to let their fields lie fallow.

It probably doesn’t mean a barren selection at your local Safeway, though.

“My gut feeling is that you are going to see a change in the more consumptive crops like alfalfa and sudangrass before you see changes in carrots, lettuce and the (high-value) cash crops,” said Kuhn.

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel