Ralph Dinosaur rocks the Farquahrts stage circa 1988. Ralph, and his lingerie, were a common occurrence at the downtown bar and eatery. Alas, all good things come to an end, and Farquahrts’ former owners, Toby and Mary Lou Peterson, took out the infamous stage in 1996 to make way for more restaurant seating. The bar was later sold and is now the Derailed Saloon./Courtesy photo

Liquor up front, pizza in the rear

Memories of a bygone Durango watering hole

by Erik R. Moeller

“It says here you went to a bartending school,” Nancy said as she held my résumé in one hand and poured me a draft with the other. Nancy managed the bar and possessed an admirable ambidexterity.

“Yep,” I answered with a tenor of pride. “Three hours a night for two weeks. The instructor said I have fast hands.”

Nancy cackled. “I bet you do. Waste of time, though. ’Round here mostly what we serve is Budweiser from a tap.”

Her words deflated me flatter than week-old road kill. I thought the course in mixology would give me a leg up, but apparently Farquahrts wasn’t looking for a graduate.

“You’re hired,” she said. “Can you start tomorrow?”

Hell yeah, I can. I’ll start yesterday. I didn’t speak these words, which is why they don’t appear in quotations, but they were tumbling in my head like kids in a bouncy house.

In the 1980s, Farquahrts was Durango’s finest rock ’n’ roll and blues joint, and the establishment served up delicious pizza. I had moved to Durango to begin studies at Fort Lewis College and quickly made Farquahrts my bar of choice. Like any worthy mountain town, Durango boasted something like one bar per 168 inhabitants, which irked teetotalers who futilely attempted to align the town’s values with its Victorian architecture.

At the time, I valued a paycheck, for the Pell grants had dried up, as had Mom and Dad’s financial support (something about me not taking school seriously). So I bellied up to the bar, ordered a brew, and handed my résumé to Nancy.

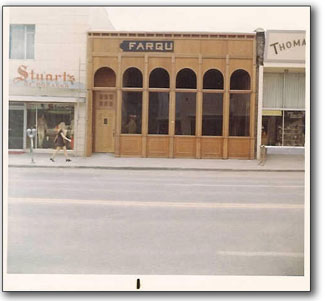

The orignal Farquahrts, under construction in 1973. Legend has it the name originated from a drunken fishing trip and is taken from the band, The Fabulous Farquar. “They added the ‘h’ and decided that was the name they were going with,” said Paige Oswald, daughter of Toby and Mary Lou Peterson./Courtesy photo |

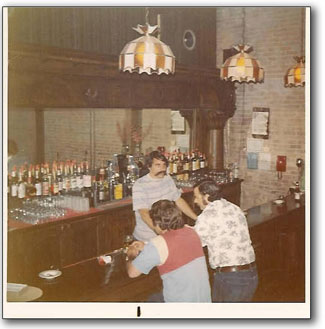

On my first shift I met Harry Eggleston III, a slight and unimposing bartender with an incongruously regal name. Unbeknownst to him, Harry the Third became my mentor, the guy I’d watch and imitate, and not just for the mechanical aspects of slinging drinks. I discovered Harry had a gentle way of keeping the clientele calm and happy, which was a tall order as the night wore on. Also, Farquahrts attracted its share of violent drunks, knife-toting bikers, even folks carrying guns, so we usually tried to maintain order, such as it was.

One night early in my career, a stout, gruff man wearing a denim shirt with the sleeves freshly ripped off walked up, plunked a Smith & Wesson on the bar, and asked if I could check his piece, referring, of course, to the six shooter. There are basically two ways to handle such a situation. One, you could panic, draw attention to the gun, and in turn scare the hell out of those whose attention you just attracted. Or, two, you could remain calm, quietly place the weapon behind the bar, and ask the nice man what he’ll have. There’s no use in escalating matters, so I did what Sir Harry would have done: I chose door No. 2.

Harry’s first aid skills didn’t rival his social acumen, however. One night he cut his hand while slicing limes. He went to the back room, cleaned the wound and proceeded to spray it with a liquid bandage. You wouldn’t want a regular Band Aid falling into the ice bin or somebody’s drink, the reasoning went. The liquid bandage is a nifty enough product, and maybe it’s superior to a regular Band Aid in some contexts, but the spray leaves a sticky residue capable of trapping flies. That night Harry inadvertently papered his hand several times in napkins and, during breaks in the action, I witnessed him struggling like a cat deep in peanut butter trying to peel the offending napkins from his gummy extremity.

The Boys at the front table roared at Harry’s predicament, and One Eye damned near fell out of his chair. Every establishment has its fixtures, and The Boys were ours. Sure as death and taxes, every evening after quitting time the five of them would saunter in and sit at the same table, which was conveniently located close to the bar. Management contemplated naming the table after them, even having the table engraved, although I don’t know which monikers would have been used because I never did learn The Boys’ full names. And it wouldn’t surprise me if the names they did use were aliases. Even One Eye had two good working orbs, so I learned to roll with the charade and not fuss over the nomenclature. Just serve them drinks. And collect on their bar tabs every Friday.

The Boys were the only customers allowed to run a weekly tab. They’d usually pay on time, and usually in cash, but occasionally they’d come up short and ask for an extension, which was always denied. One Friday, Lawrence threw a hissy when he couldn’t pay his tab and the bartenders refused to serve him. He flew off the handle, waving his arms erratically and screaming threats and insults at the bartenders and waitresses. One bartender flashed the lights over the bar, which was our signal to the bouncers that trouble was brewing, and two bouncers appeared out of nowhere, picked up Lawrence by the arm pits and drug him out the door. “You’re 86ed,” Nancy yelled as Lawrence dug in his heels, his boots etching a two track in the carpet that was discernible for a week

About two months later, management 86ed The Boys – all of them – when their debate over a sign on a wall sank into debauchery and shocked a church group from Texas. The sign read, “Liquor Up Front, Pizza in the Rear,” which was sort of a road map of Farquahrts. Indeed, the bar was located at the front and a small pizza parlor occupied the rear, although one could enjoy a pie up front until 9 p.m. when the bands took the stage. Never ones to let innuendo lie, The Boys ultimately agreed on a lascivious rewrite, raised their mugs 4 in triumph and announced it to the entire bar.

Three large fatherly figures wearing cowboy hats and supersized belt buckles began to rise from their chairs as mothers covered their daughters’ ears and leered. Others simply shook their heads in disgust. “Come on, Boys, at least wait until the young ones are gone before acting like idiots,” a doorman said. “Kiss our collective asses,” replied The Boys in unison with another hoist of mugs. I didn’t see The Boys for another two weeks.

Our house band at the time was Ralph Dinosaur and the Fabulous Volcanoes, who drew raucous patrons who kept the tip jars full. The band wasn’t the tightest, musically speaking, but nobody cared. The music was fun, and Ralph’s shtick was comical. By the second set, Ralph would jump on stage wearing a wig and a dress with a brassiere strapped on the outside and perform like the world was right. He’d shoulder his Strat, sidle up to the microphone and belt out “I Wanna Be Sedated” as his second-hand Ann Taylor exposed hairy shins, and his prominent Adam’s apple pulsed under a three-day scruff. Ralph donned the feminine ensemble, but he was no drag queen.

String Cheese Incident and Leftover Salmon also played a few gigs at Farquahrts in the late ’80s, long before there were leftovers. Clarence Clemmons blew his sax on our stage, and Big Pete Pearson tore down the house with his blues. Matt “Guitar” Murphy from the Blues Brothers played a gig or two, and the Cowboy Junkies hitched up their ponies on one occasion. Hot Tuna indulged us, too. Walt Richardson and the Morning Star Band packed the joint several times with their grooving reggae. The dreadlocked fans didn’t tip well, possibly due to ganja’s short-term amnestic effect, but the staff always dug Walt and his band. Local musicians often demonstrated Durango’s booty of talent, which made me ponder why half-ass musicians can wind up with record labels while truly good performers don’t make it past the street corner.

String Cheese Incident and Leftover Salmon also played a few gigs at Farquahrts in the late ’80s, long before there were leftovers. Clarence Clemmons blew his sax on our stage, and Big Pete Pearson tore down the house with his blues. Matt “Guitar” Murphy from the Blues Brothers played a gig or two, and the Cowboy Junkies hitched up their ponies on one occasion. Hot Tuna indulged us, too. Walt Richardson and the Morning Star Band packed the joint several times with their grooving reggae. The dreadlocked fans didn’t tip well, possibly due to ganja’s short-term amnestic effect, but the staff always dug Walt and his band. Local musicians often demonstrated Durango’s booty of talent, which made me ponder why half-ass musicians can wind up with record labels while truly good performers don’t make it past the street corner.

Notwithstanding such injustice, when the music stopped and the clock struck two, the doormen would lift drinks from the tables and clear the venue. “You don’t have to go home, but you can’t stay here,” they’d yell as the crowd herded toward the exits. The help would stack the chairs and whip out their Mini-Mag flashlights to scour the floor for treasure and contraband. Occasionally, a lucky scavenger would find paper money or a baggie containing goodies better left unnamed lest the statute of limitations hasn’t run out.

On slower nights, we’d close shop early and race to other bars for last call. Other times, the crew would drift with the band to an after-party where the lucky chaps greeted first light with a smile and a companion. The lonesome souls cradled their pounding heads and drew away from the light with a hiss, a belch, and hair o’ the dog tempered with tomato juice.

No matter my condition the next day, I usually had a respectable wad of tips in my pocket that I’d spend on a late breakfast, a night at the movies or school supplies. Because of my employment at Farquahrts, I earned enough money to pay for a college education and rent, which was no small feat in the 1980s when Durango’s tourism economy sprung loose and real estate prices soared. Real estate was so hot it seemed that half the town enrolled in night classes to become Realtors. I stuck it out at Fort Lewis College and earned my B.A. in 1989. I also picked up some useful knowledge, even solved a logical conundrum that stared down at me during each shift: the tantalizing words on a simple black-and-white sign over the bar that tempted the unwitting with the elusive promise of “Free Beer Tomorrow.”

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel