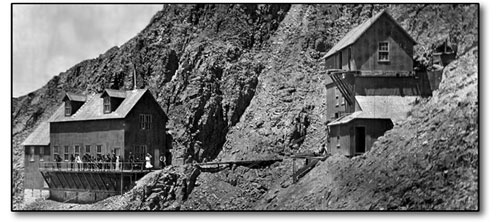

The Old Hundred Boarding House clings to the side of Galena Mountain, near Silverton, in this 1906 photo. While there are several efforts to preserve the visible relics of the area’s rich mining past, there are also efforts to erase a less visible part of mining’s legacy: decades of toxic run-off from abandoned mines. The problem has proved a difficult one to tackle, with many mining companies long defunct, leaving local residents, good Samaritans and taxpayers holding the bag./San Juan County Historical Society

A blip in geologic time

A somewhat brief history of mining’s other legacy

by Zack Hively

A week after disaster struck at the orphan Gold King Mine, news of the 3-million-gallon spill has spread almost as fast as the toxic plume of custard-yellow water.

However, this problem is not new. Even prior to the spill, 800 gallons a minute poured consistently out of the mouths of four abandoned mines around the ghost town of Gladstone. That’s more than 1 million gallons of wastewater containing heavy metals, including zinc, copper, cadmium, iron, lead, aluminum and manganese, flowing down Cement Creek into the Animas every day.

The toxic metals are constants in the river system. They are just not normally Tropicana-obvious. And they do more than complicate the Animas’ qualification for Wild and Scenic River designation – they affect the entire ecosystem, and the small-town economies, that depend on the river.

Life in the Upper Animas is rapidly declining. Three of the four fish species typically found there have vanished, and the U.S. Geological Survey has shown that both the diversity and quantity of insect species there are notably low. The water quality at Baker’s Bridge is at its worst point in 20 years, according Peter Butler, of the Animas River Stakeholders Group (ARSG), with a definite drop in the number of fish and crucial macroinvertebrates since 2005. Purportedly, the levels of toxins present no danger to humans, only to the macroinvertebrates which the fish eat. What’s bad for the goose is, apparently, just dandy for the gander.

Rusty heavy-metal laden water from a culvert gushed into Cement Creek as recently as the afternoon of Sat., Aug. 8 - two days after the catastrophic gold mine spill. It is estimated some 800 gallons of acidic mine waste escape abandoned mines in the area every minute, eventually finding their way into the Animas./Photo courtesy Elizabeth Stilley |

The constant spillage is partly the legacy of old mines, but it is also the result of contemporary stop gaps. When the Sunnyside Mining Co. closed its Silverton-area operations in 1991, the company had little desire to continue treating the 1,200-1,600 gallons of water per minute running from its mines. So it struck a deal with the state whereby it could plug the outlet tunnels with bulkheads and simply treat the leakage. Sunnyside continued to do so until 2002, when it passed off responsibility for the treatment plant to another company. The plant was shut down in 2004 – corresponding with the drop in water quality at Baker’s Bridge.

The plugged outlet tunnels caused the water table to rise. The water escaped from the adits of four previously dry orphan mines. These mines – the American Tunnel, Mogul, Red and Bonita, and Gold King No. 7 – issue the contaminated water straight into Cement Creek.

Zinc is the most serious and concentrated of the contaminants. Butler has estimated that 28.5 tons of zinc emerge from the four primary draining adits each year, accounting for nearly a quarter of the total amount recorded in the Upper Animas. The levels of zinc in the Animas at least as far south as Baker’s Bridge are toxic to animals. Lead is more toxic, but its concentrations are lower.

To be sure, some amount of these metals occurs naturally, owing to the bleeding metal-rich rocks in the mountains. Some scientists even suspect that Cement Creek has never sustained aquatic life due to its natural acidity. However, mining has exposed and removed more rock than natural processes. Water accelerates the leaching process in these mines.

So why isn’t someone simply cleaning up the contamination? It’s not for lack of desire – the ARSG, for example, exists in large part to ensure the survival of the Animas through community self-determination. Yet even with the support of the Environmental Protection Agency, the ARSG cannot hazard a remediation effort of the primary leaking mines around Cement Creek. The group has feared liability under (ironically enough) the Clean Water Act.

The trick here is that the Clean Water Act requires a 100-percent cleanup of a point-source hazard. (Point-sources are uncontained origins of pollution traceable to a single point. A jet engine is a point-source of noise pollution. The San Juan Mountains are not a point source of runoff pollution, because naturally occurring zinc comes from the entire watershed rather than a single identifiable point, such as an old mine adit.)

The requirement prevents corporate polluters from getting off the cleanup hook, but a likely consequence is that anything short of an absolute cleanup opens a good Samaritan to a lawsuit. No one has yet to actually sue a good Samaritan group, though the possibility is enough to prevent groups like the ARSG from taking the gamble.

Sen. Mark Udall, D-Colo., and Rep. Scott Tipton, R-Colo.,

attempted to remedy this scenario by introducing the Good Samaritan Cleanup of Abandoned Hardrock Mines Act in 2013. The bill was referred to committees in both the House and the Senate, where it eventually died. “We still have a liability issue we can’t overcome,” Butler said in a phone interview.

Even though its ability to address toxic runoff is stymied, the ARSG has still attempted to prepare remediation efforts on the area’s water, including holding an online competition for creative solutions. “We’ve investigated different options, gotten different ideas,” Butler said. “But again, it’s an issue of how much time you want to spend on this when you can’t do it. And there’s no money for it.”

For instance, no local or regional environmental group has anywhere near the budget needed to operate a proposed limestone water treatment plant: $12 to $17 million, with $1 million a year in operating costs from now to eternity. Cleanup would incur ongoing expenses because of how leaking mines differ from contained solid waste contaminants. “With a draining mine, it’s ongoing,” Butler said. “That water comes out year-round, so you’ve got to deal with it regardless.”

One possible solution has always been Superfund, which sounds like a monetary superhero and in many ways is. Superfund is a program under the EPA that enables the federal government to oversee hazardous waste sites. The EPA offers legal protection to the local entities with which it collaborates, and it also compels those responsible for pollution to manage or pay for the cleanups.

Yet Silverton has resisted Superfund aid for years. Superfund designation could affect property values, shift local control to outside entities, and turn tourists (and their dollars) elsewhere. Relying on the ARSG and other good Samaritans kept issues in the family, as it were, and thus kept the problem quieter.

Even so, Silverton has become more publicly curious about pursuing serious cleanup of the orphan mine leakage. In April 2014, officials from the EPA met with San Juan County commissioners and Silverton residents to answer questions about Superfund designation. The EPA officials assured the assemblage that the agency would not pursue Superfund without Silverton’s approval, and that the cleanup process would continue to be a collaborative effort with the community.

While Superfund status has not been enacted, the EPA has kept active in assessing the mines. After opening the Red and Bonita to investigate its insides, the EPA decided to install bulkheads to stem the flow. The Red and Bonita consistently emits 300 gallons per minute alone, though this year’s weather upped the output to 500 gallons. Completion of these bulkheads was scheduled for the end of September. In order to monitor possible changes in discharge from other mines, the EPA planned “to remove the blockage and reconstruct the portal at the Gold King Mine.”

This process triggered the plume making its way through Durango and into New Mexico. The spill is obviously a mess. But without consistent and reliable treatment of the continuous leakage, the same toxic metals were already entering the Animas River beforehand. Only now, we can actually see them.

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel