Gophers Inc., LLC

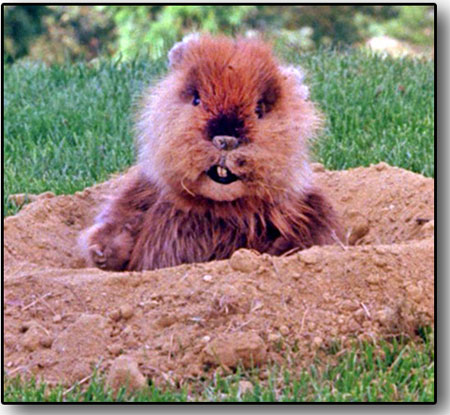

More than a few gophers excavate on my 3 acres, which is inconvenient, but still preferable to having Kinder Morgan here, because gophers don’t drive pickups with flashing yellow lights, break up the blacktop on county roads, erect tall rigs that flash at the horizon all night, or transport tankers full of dirty water to settling ponds in New Mexico. Gophers are much more subtle. Tiny mounds appear every morning, dirt ground fine as coffee beans, which is how I know they’ve been awake all night, busy with their workload. They are classic hoarders, stuffing their pouchy cheeks, not with profits, but with grass, nuts, insects and leaves, frolicking under the moonlight on a feast of roots and salad greens.

The internet can supply a wealth of material on the little rodents, enough to make me think I understand how gophers operate beneath the surface of my land. Unfortunately, most oil and mining companies prefer the general public has as little knowledge as possible about their operations. For example, CEO Richard Kinder supposedly earns a salary of $1 annually, with no bonuses or restricted stock options, according to Wikipedia, yet Forbes Magazine places his wealth at about $11.8 billion. That’s a lot of greens.

But getting back to my back yard, the pocket gopher includes more than 35 species, all of them confined to burrows in the Americas. When I learned that no gophers populate the Middle East, I was relieved. Dependence on foreign gophers for our tunneling could make us weak.

The reason I have been studying the pocket gopher is that as my fleet of gophers moves closer to my gardens and house, it’s all too likely their presence may literally undermine my lifestyle. I am assured, however, that oil and mining exploration can do nothing but enhance our local economy, so I accept the company’s presence, but mostly because there’s little I can do about it.

As for the gophers, many products are marketed to rid homeowners of their destructive presence, but I’m here to report that none of them work. The film “Caddy Shack” should have made it clear: gophers are the coyotes of the rodent world. They are tricksters and have a knack for survival. I should just accept the gophers’ existence and leave them alone, but our ideologies are at odds.

In eight years at my current location, I’ve only seen one gopher scurry across my lawn during daylight hours, which explains why nobody organizes gopher hunts with trophies and cash prizes, much like they do to eradicate coyotes and prairie dogs. It’s nearly impossible for a hunter to call gophers to the surface. Their working hours are in the dark and all that scraping and digging gets suppressed by a dense layer of soil.

As most residents find out when they purchase their homesteads, the mineral rights below the surface have already been sold, but not to the gophers. If I decided to start my own tunnel in the back yard and I hit, say, a profitable vein of something, officially it wouldn’t belong to me, unless it’s just roots or bulbs. And then I wouldn’t be surprised if I’d be sued by a consortium of rodents with no appetite for an oil company’s style of extraction. Profits for the gopher must be organic and thoroughly digestible.

I’ve had marginal success when it comes to trapping the varmints. They sneer at the idea of live traps. I’ve been forced to use the Victor gopher trap. It’s the least expensive, and really, it’s nothing more than a mouse trap with attitude. The jaws must be carefully pulled apart and set so two spikes, when tripped, pierce the gopher from both sides. It’s a nasty piece of business. The only thing that makes the prospect of stopping the gophers bearable is the knowledge that they’re likely to outwit my best laid plans.

With a 4-foot shank of rebar, I probe the dirt around each mound in a widening circle until I find the direction of its most active tunnel, then I sink the blade of my spade into the earth to sever the artery, place one trap at each exposed opening, and cover my intrusion with a piece of cardboard to prevent any light from reaching the jaws of my double roadblock. I followed these internet instructions precisely, and I thought I had my gopher problem solved.

The next morning I walked to the worksite and removed the cardboard only to find the hole I dug completely backfilled with dirt, my traps buried beneath the rubble – both of them triggered but empty. Just 20 yards away, another series of fresh mounds and a muffled, earthy sound that might pass for sniggering, which coincidently is what I’d expect to hear if I come by the oil company’s corporate office late at night with a flashlight and the necessary tools to instigate an audit.

– David Feela

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel