|

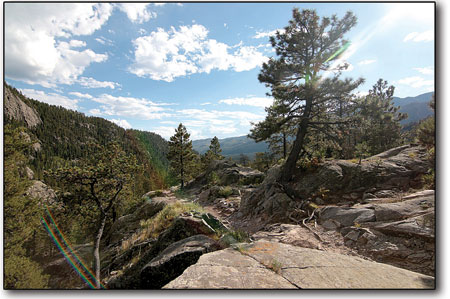

The Weminuche Wilderness Area is the largest wilderness area in Colorado, encompassing 499,771 acres of rivers, lakes, mountains, trees and trails in Southwest Colorado./Photo by Jennaye Derge

|

Call of the wild

Fifty years after Wilderness Act passes, the fight to protect persists

It’s defined as much by permanence as it is by change. Landscapes meant to outlast humanity’s fickle nature also measure the impacts of an ever-changing climate.

Protections are provided in perpetuity by a dynamic congressional process, where political names and lobbying interests shift with the times but the game remains much the same.

As the 50th anniversary of the Wilderness Act of 1964 is celebrated across the country, local residents are still fighting to keep the wilderness wild.

JusttheFactsWhat: Walk for Wilderness and Family Fun Fair

When: 9 a.m. - 1 p.m., Sat., Sept. 27 Where: La Plata County Fairgrounds More info.: Event includes Anniversary Walk, educational and interactive booths, and the San Juan String Band performs; www.wilderness50th.org |

What could have been the latest addition to the nation’s wilderness system, adding another 38,000 acres to the more than 100 million nationwide, has fallen victim to that fickle federal process in the United States Congress.

Last week an amended version of the Hermosa Creek Watershed Protection Act moved through the Natural Resources Committee in the House of Representatives, much to the surprise and dismay of those who spent years crafting the original legislation.

“It’s nothing new,” explained Mark Pearson, former director for the San Juan Citizens Alliance who’s currently writing a book on the history of the Wilderness Act in Colorado.

“It’s disappointing because people thought it was different this time … at the end of the day, Congress is what it is.”

Even the Wilderness Act struggled with congressional committee politics in 1964. Rep. Wayne Aspinall, a Colorado Democrat and chairman of the House Interior Committee in 1963, was holding up the original act. His reason for letting it stagnate in committee was that mining interests who supported him would lose their ability to explore for minerals.

Two days before President John F. Kennedy’s assassination on Nov. 22, 1963, he phoned Aspinall in an effort to move the bill forward.

Following Kennedy’s death, Aspinall allowed the bill through to the House floor. Partly because of the promises he made to the president and partly because of concessions the two agreed upon, including a 20-year window for miners to explore wilderness lands.

Less than a year later, President Lyndon B. Johnson would make it official. So, Johnson may have signed the act into law, but Kennedy made the phone call.

A similar fate befell the Weminuche as it winded its way through the legislative maze in Washington.

In its final days as a bill, an Arizona congressman threatened to hold up the whole process unless the lands covering Goose and Trout creeks near Creede were left out of the bill. A timber company and supporter of the congressman wanted to keep those lands open to logging. “That was his pound of flesh,” Pearson said.

Those lands weren’t designated wilderness until 1980, when the Weminuche was expanded.

Just like the Weminuche, Hermosa Creek has its hurdles. First introduced in the Senate in 2012 by Sen. Michael Bennet, D-Colo., and later in 2013 by Rep. Scott Tipton, R-Cortez, the Hermosa Creek Watershed Protection Act was born from the debates and discussions of a diverse group of local river users and stakeholders, from boaters and mountain bikers to property owners and politicians.

They spent years developing the legislative language that went into the original bill. Some changes were expected as it made its way through the Natural Resources Committee in the House.

Specifically, a section was to be added that would allow recreational snowmobile use in the West Needles area near Molas Pass. The management plan for the San Juan National Forest, recently released by the Forest Service, no longer allowed for commercial or private snowmobiling.

Conservationists, local leaders, snowmobilers and others got together and created an addition to the bill that would allow for continued snowmobile use, both commercial and private. The West Needles area, where it would be allowed, would be designated by Congress upon the act’s passage. The specific trails used would be determined later by local Forest Service officials.

Leave no trace and other tips for keeping it wildIt might seem secondhand to many Colorado residents, who have 40 designated wilderness areas in the state and another 40 or so proposed. But not everyone is aware of some of the potential challenges to keeping the wilderness wild. Matt Janowiak, district ranger for the U.S. Forest Service Columbine Ranger District in Southwest Colorado, said it can be difficult to get nationwide outreach when it comes to letting the public know the rules and regulations for visiting wilderness. Most people, however, are good stewards of the land. “That’s the untold story,” he added. The vast majority of visitors to the wilderness leave no trace. The only sign they ever stepped foot on the land is their signatures on the sign-in sheets at the trailhead. Points to remember:- No more than 15 people in a group. Many people want to share the joy of experiencing the wilderness. Therefore, it’s easy to grab lots of friends or family and head out into the Weminuche. But keeping the party to 15 or less also keeps the human footprint to a minimum, which is the point of wilderness. - Open up the open space. There’s no rules or laws against enjoying the same view as everyone else, but sometimes it can cause unintended consequences. More than 350 people, for example, can visit the Chicago Basin area in the Weminuche in just one weekend. It’s both a testament to the area’s beauty and a reminder of the need to protect it. According to the act, wilderness is “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man.” - Leave no trace. After all, people are the visitors. – Tracy Chamberlin |

What came out of the Natural Resources Committee was something very different.

For one, it wasn’t just the area boundaries that Congress would be designating. It was also the specific trails, meaning control no longer was in the hands of locals. It was in the hands of legislators in Washington and could not be adjusted for any reason.

Other sections of the bill were also changed, adding qualifiers that Jimbo Buickerood, public lands coordinator for the San Juan Citizens Alliance, said not only cloud protections the original document provided but make significant changes that diminish those protections.

“It’s disappointing that the community’s intentions that were worked on for years and were so clear were 4 not reflected in the amended version that the congressman put forth,” Buickerood explained.

He pointed to one change he said could actually open the door for development in an area designated as wilderness.

The original version stated that, “Nothing in this section affects the potential for development, operation, or maintenance of a water storage reservoir at the site in the Special Management Area …”

However, the amended version reads, “Nothing in this Act shall affect the development, operation, or maintenance of a water storage reservoir, including necessary ancillary roads and transmission infrastructure, at the site in the Special Management Area …”

Just a few words here or there can have a dramatic effect on how the law is later enforced by federal agencies and interpreted by the courts, according to Buickerood.

The amended version of the act still has several steps to take before coming to the president’s desk for a signature, including making it to the House floor for a full vote and passing the Senate.

“The minor amendments … in no way have changed the outcome of the legislation’s goals agreed upon by all of those who have been engaged throughout this entire process,” Tipton said in a press release following the bill’s passage through the Natural Resources Committee. “… All of the major wilderness and conservation provisions remain intact.”

But not everyone who has been engaged throughout the process does, in fact, feel the major provisions remain intact. Nor do they consider the amendments minor.

|

The past is littered with wilderness advocates, although many didn’t carry that tag, going back to the 1800s with Ralph Waldo Emerson who penned, Nature, and his follower Henry David Thoreau who wrote Walden. Co-founder of the Sierra Club, John Muir, famously fought to protect the Yosemite Valley; and, President Theodore Roosevelt’s name is inextricably linked with national parks, after having established several in 1906, including Mesa Verde. Local wilderness author Mark Pearson pointed out two additional proponents that ultimately shaped the way America treated its wild spaces. In 1919, Arthur Carhart was asked to lay out cabin sites surrounding Trapper’s Lake, in northwest Colorado. Thinking it was a bad idea to privatize the lake and surrounding area, he persuaded his superiors at the U.S. Forest Service to keep it wild. Although his move is considered the genesis of putting wilderness before development, Carhart was not christened its father. That honor fell upon Aldo Leopold. He convinced the Forest Service in 1924 to establish the Gila Wilderness, the first of its kind, leading to the creation of primitive areas in the 1930s and eventually the idea of wilderness areas in the 1950s. |

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel