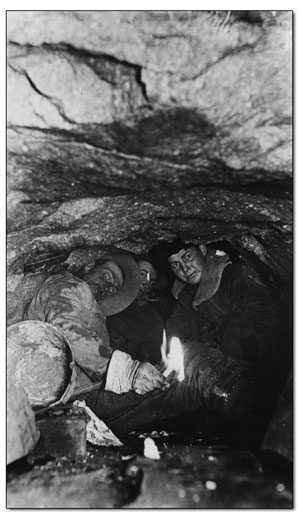

An unknown photographer took this photo in 1910 from inside the Lake Hope tunnel near Telluride. It’s one of 85 in Tough Men in Hard Places: A Photographic Collection from the Western Colorado Power Co. Collection, from the Center of Southwest Studies./ Courtesy photo

Power to the people

Local author reveals how Southwest Colorado became electrified

by Tracy Chamberlin

The images of those who could, along with the ones that helped them make it happen, are captured within the pages of Tough Men in Hard Places: A Photographic Collection, by Esther Greenfield.

|

And, not just understand it, she explained. Command it. Direct it. Manipulate it. At the turn of the 20th century when the West was still wild, who could think to capture hidden electrons and use them to light the darkness?

Greenfield’s book features a sampling of images and interviews from the men who built the first electrical infrastructure in Southwest Colorado. It serves as a visual record of the awesome machines they created, the power plants they erected, and the deaths and disasters they overcame.

As for Greenfield, her journey was sparked with a visit to the Center of Southwest Studies at Fort Lewis College.

She studies arborglyphs, and went looking for information on a resident whose signature she saw scratched on the side of several aspen trees in the area. She called him a “really bad cowboy.” After speaking with archivist Todd Ellison, she instead found herself being recruited as the newest volunteer at the center.

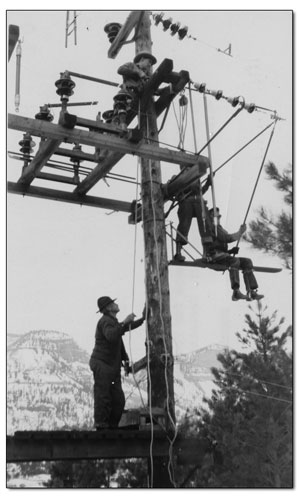

Workers install dead-end clamps on the Rockwood switch tower, March 1929. Both photos, taken by unknown photographers, are from Tough Men in Hard Places and a part of the Western Colorado Power Co. Collection, Center of Southwest Studies./Courtesy photo |

As Greenfield went through the photos, she said they began to grab her.

The first one to fire her imagination was that of a riderless horse on Cascade Creek, surrounded by wooden poles and electrical wires on a barren, snowy landscape. She said in the foreground of the photo was the shadow of the man taking the picture. She copied the photo and tucked it away, not even sure why. “Then, as I went along, I found more pictures like that.”

Greenfield eventually revisited that photo of the riderless horse, turning the inspiration into a 2012 story for the Durango Herald, titled “A powerful look at power,” which caught the attention of a publisher.

She soon found herself sorting through hundreds of photographs from the Western Colorado Power Co. collection. That pile was whittled down to 150, and then to the 85 that made the final cut.

“I’m an accidental book author,” explained Greenfield, who turns 71 this December. Writing a book was not part of the retirement plan. For her, the whole experience has been just like having dessert.

At the heart of Tough Men is a man named Philip “P.C.” Schools, who began his journey out West when he ran away from home as a teen-ager. Frustrated and expelled from high school in northern Idaho, he wrapped up his belongings in a red bandana and hit the road.

Although he left home without finishing school, he would end up earning two degrees in mechanical and electrical engineering. He would also end up capturing and preserving the collection that inspired Greenfield.

As a chief engineer for the Western Colorado Power Co., Schools wanted to capture the electrification of Southwest Colorado. In some photos, he’s behind the camera. In others, he’s in front.

Along with the photographs, Greenfield also discovered a box of 100 interviews with linemen, patrolmen and other power company employees. Collected in 1939, the stories recount the dangers and humors of building the first electrical infrastructure in the region.

One Montrose customer, who thought a power pole was too close to his barn, asked the Montrose Light Co. to move it in 1905. They never did.

The customer recounts how he dealt with the lack of response – he broke the insulators and pushed the pole over. When the company replaced it, he said, the pole was put “in the right place.”

In 1909, when lights went dim in Western Colorado, customers would call the Hotchkiss Packing & Power Co. and ask them to “Throw on another shovel-full of apple peelings!” The rumor was that the furnace ran on dried apple peels.

In the beginning, a postman from Montrose said, the lights often looked like fireflies and weren’t on very often. Typically, the power was on from the early morning until about midnight. It wasn’t until the late 1920s that electrical service became available 24 hours a day.

“It’s hard work, very hard work,” Greenfield said.

Particularly in the San Juan Mountains, where an average day at work meant strapping on snow shoes at 12,000 feet with winds blowing and sleet falling.

One of the most common environmental dangers were avalanches. In seconds, they could take out thousands of feet of power lines – and even lives.

Other upcoming events:- Book Signing with Esther Greenfield, author of Tough Men in Hard Places, 4 p.m., Oct. 23, Fort Lewis College Delaney Library. swcenter.fortlewis.edu. |

Stories of the slides, burying men up to their armpits or carrying them hundreds of feet, litter the interviews.

Greenfield writes how the men were paid well for the dangerous work. But, for some, good money wasn’t enough. Workers would simply walk off the job, never to return. At times, the turnover rate was 75 percent.

Schools is quoted in the book explaining how the linemen and patrolmen were also deputy sheriffs. “Back in those days one had to be tough,” he said.

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel