|

|

Backyard Spartan

Local endurance racer prepares to battle the Death Race

by Ben Brashear

Dustin Partridge leads me out his kitchen to his back yard obstacle course, nestled in the tall grass of the Animas River Valley.

In front of us stands an 8-foot wall built from reclaimed 2-by-6’s. Suspended from an old-growth cottonwood nearby is a 20-foot rope climb and a 50-pound bucket hoist filled with river rocks. Stumps litter the yard, serving as steps for plyometrics, and a backdrop for spear throwing sits against the far fenceline.

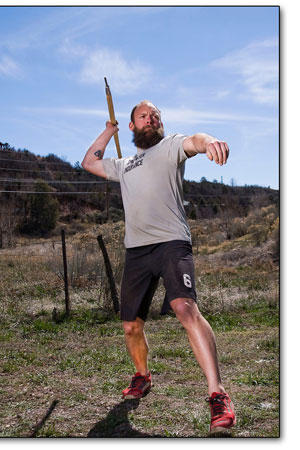

In one hand he carries a homemade javelin and with the other he gestures as he explains that in between his time working at Natural Grocers and putting his mechanical engineering degree to use re-designing backpacking gear, he is here. Training.

With his high-and-tight haircut and squared-off beard extending to his chest, it’s as if we somehow slipped back in time to a Greco-Roman training camp. Which isn’t too far off from the truth.

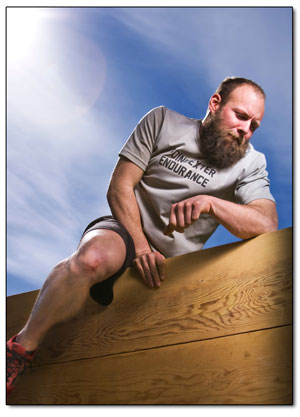

Partridge squares up for the spear toss. Death Race participants can expect a myriad grueling mental and physical feats interspersed with obligatory burpees, of course./ Photo by Ben Brashear |

Partridge, 33, could be considered a modern day warrior. An endurance-race enthusiast, the Durango resident was a top-50 finisher of the popular Spartan race series in 2013. Comprised of races that vary in length and difficulty from 5km sprints to the 26-mile “Ultra Beast,” to the aptly named 30-plus-mile summer and winter Death Races, more than 600,000 people competed in Spartan races last year. The races, which started in 2005, are now held throughout the world, including venues in North America, the U.K., Slovakia, and even South Korea. In 2013, Spartan partnered with Reebok, which helped garner the Spartan World Championship airtime on NBC and made the series one of the most alluring obstacle races out there, with a purse of over $300,000. Its founders are even pushing the race for an Olympic bid.

Although Partridge has the Worlds in mind, his focus reaches far beyond any monetary value. He is preparing for what may be one of the most difficult obstacle races he will face this year, or ever: the Spartan Death Race. A 48-hour testament of strength and resilience, the Death Race is scheduled for June 27 on Spartan Race co-founder Joe Desena’s home turf in Pittsfield, Vt.

Desena wanted to create an event that would replicate the challenge he encountered racing numerous Ironmans and ultra endurance events while remaining accessible to anyone willing to challenge his or her paradigm of can and cannot.

Partridge explains that the Death Race is a race without a known finish line, taking competitors anywhere from 24 to 48 hours to complete. And in spite of its $600 entry fee, it doesn’t even offer prize money; just a plastic skull to those who finish. “The race isn’t even fair. One year they made competitors carry rocks throughout the race but the rocks varied in size from 5 pounds to 30 pounds for each racer,” he said. “With only a plastic skull for an award, it’s more about pushing you to your limits.”

Partridge is continually trying to redefine his limits, as evidenced by his strenuous training regimen. Every racer can expect to chop a cord of wood, run at least 30 miles, execute spear throws, and perform countless burpees.

“The consequence for failing to complete an obstacle at a Spartan race is a mandatory 30 burpees,” Partridge says.

He lifts his right leg and pushes down his sock to show off a patch of scar tissue on his shin. The result of countless hours of rope climbs, the tissue never seems to heal. Partridge shrugs it off.

He first became interested in endurance racing a few years ago when hiking the Continental Divide Trail. “I ran into a woman whose husband was training for the Leadville 100 and I thought that was the stupidest thing you could do. A year later, I was at the start line,” Partridge says while tugging at his beard. “Most people say the Leadville 100 is one of the hardest running races to do as a first hundred-miler, but I wouldn’t think of doing it any other way.”

Finding the most difficult challenge physically and mentally is Partridge’s goal in racing, and in life. The Leadville 100 was his first ultra-marathon, and once he caught word of the Toughest Mudder – a 24-hour version of the Tough Mudder obstacle race, held in New Jersey – he sought out the nearest 5k qualifier. From there, he dove straight into the hellish 24 hours of frigid 30-degree swims, wall climbs, and slogging through hypothermia. Partridge did not complete that race, which was in 2012, due to hypothermia. But the experience ignited in him a passion for pushing his limits. “More or less you have to enjoy not being comfortable, and yeah, I kinda do enjoy that,” Partridge laughs. “Every race is a personal break through and that’s why you do it.”

The following year saw Partridge splitting his time between Colorado and Connecticut training daily for his next 24-hour Toughest Mudder. “That’s all I thought about until my next race. I focused on cold water training by swimming in the Atlantic Ocean and in my brother’s backyard pond in Connecticut,” Partridge says.

In Durango, the scene is markedly different. Chickens cluck and purr between our feet and the smell of sun-warmed grass washes over our conversation. One could almost get lost in this bucolic calm – that is, until Partridge suddenly stops and squares his shoulders with the spear toss.

“I couldn’t get the spear throw last year,” Partridge says as he looks over his shoulder and then back at the target.

Standing about 30 feet away from the hay bale, the howls of endurance and exhaustion re-playing through Partridge’s mind are almost audible as he furrows his brow and takes aim. He pads his feet, which are fitted with red and white minimal running shoes, into the dirt. Across his barrel chest reads, “Poindexter Endurance,” a nod to his calculated persistence and logical approach to racing.

“Mental preparation will be what separates those who do well,” Partridge says as he snaps his arm forward, releasing the spear with such ferocity that his body recoils and pulls his feet off the ground. The spear sits buried to the hilt in the board a few inches low of the target.

Partridge retrieves the spear marveling that it went all the way through the backdrop and returns to square up once again. The late afternoon sun begins its descent toward the horizon, and Partridge continues to fire off shot after shot gaining confidence as he begins to consistently hit the target. “It’s not like a marathon or your typical running race where you know exactly what you are going to get,” said Partridge. “With the Death Race, you just go and keep going, you don’t know what you’ll get, but you just keep going.”

He will be out again training tomorrow and the next day – adapting his body and mind to the fear of the unknown, the fear of a race with no end. For Partridge, the ability to maintain such resolve comes down to one thing beyond his nutrition and all the hours spent training, which can verge on the masochistic: his girlfriend, Jen Smith. “She enables me in being successful. She laughs at me; feeds me and crews at my races when she can. She’s even going to come out and race in Vermont this year,” Partridge smiles. “She is right there with me when she can.”

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel