Garden Mandala

by Ari LeVaux

With the days getting longer and seed catalogs replacing holiday cards in the mailbox, a gardener’s thoughts inevitably turn to that blank patch of dirt where, if all goes well, he or she will spend an inordinate amount of time this summer.

With the days getting longer and seed catalogs replacing holiday cards in the mailbox, a gardener’s thoughts inevitably turn to that blank patch of dirt where, if all goes well, he or she will spend an inordinate amount of time this summer.

Why we do this is not a simple question. If all you want from your garden is the calories, there are much easier, dependable and less time-consuming ways to get them. If you like the exercise, the fresh air and the connection with the natural world and your food, that’s another story.

A garden is like a toy farm. It’s anatomically correct, all the parts work, and it’s capable of delivering the same benefits, risks and intangibles of its big brother, the diversified vegetable farm. On a farm, these outcomes exist with greater intensity, including the feelings of joy, harmony and productivity as well as the aches, pains and heartbreaking moments of desperation, futility and failure.

Josh Slotnick, a farmer in Montana, believes this work, while often challenging, makes you a better person. “Small groups doing humble labor with tangible results is a transformative experience,” he told me.

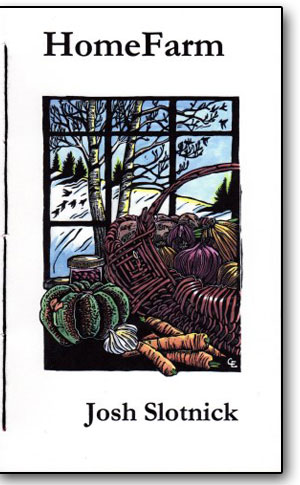

His debut collection of poetry, HomeFarm (Foothills Publishing), is a glimpse into the life of a farmer. The highs and lows he traverses are so dizzying that the book could have been called “Manure-Splattered Double Rainbow.” But as bipolarizing as this lifestyle may seem, the farmers I’ve met seem to share a certain even keel, as one might hope from ship captains that steer valuable cargo through potentially stormy seas.

The introduction to Slotnick’s book offers an intriguing clue as to how it is that manual labor, done humbly, might help to give farmers – and gardeners, I like to think – this grounding and make them better people.

He compares his vegetable farm to a mandala, a Buddhist tradition that’s part meditation device and part performance art. Tibetan monks periodically visit the University of Montana, Slotnick explains, and spend a week or so creating a 10-foot square painting out of carefully arranged grains of colored sand. The result, ornate and dazzling, is cheerfully tossed in the river upon completion. The making and letting go of the mandala is an embrace of impermanence and of process over product, Slotnick explains, and he can relate. What was brown “homogenous topography” in the off-season is a diverse ecosystem by the end of July, he writes in the intro. A few months later it’s brown again.

“You can walk into the corn, over your eyes, and feel the humidity swell, and if you stop moving and stand rock still, the sound of bees fills your ears, the squash becomes an impenetrable sea of spiky green, the flowers, carrots, all of it, fill every sensory level, and then come fall, we mow it down and till it in – pour the sand into the river – and it’s a flat sameness once again.”

In between the periods of homogenous topography that define the growing season, Slotnick is fixing things, moving miles of irrigation pipe, dealing with angry neighbors about a messy pig slaughter and haggling with a shaggy customer at the farmers market who wants to save a little beer money by using the bargaining skills he learned in Central America to shave pennies off the price of broccoli.

Slotnick’s shoulders were sore and burnt from moving sun-baked irrigation pipe in order to keep those broccoli plants alive, and the hipster’s attempt to bargain him down 50 cents on a bunch not only annoys him but makes him wonder, in the poem “Triple Digits,” what it would be like to not care about water.

While he envies the people who can simply jump in the river on a hot day, Slotnick doesn’t appear ready to trade in those searing sections of irrigation pipe. Carrying 50-foot lengths, one on each shoulder, is a meditation itself that recurs within the season-long mandala. On an evening moving pipe with his teen-age son, it gives Slotnick an opportunity to reflect on the bittersweet fact that the nest will soon be empty.

How many evenings have you and I done this,while the sky goes pink to orange

the mountains flatten to silhouette in the west

we flop lines of pipe from one side of the mainline to the other juggle end caps, T’s and elbows

soak the big squash for hours

keep the seedbeds damp

the mowed beds dry

where I will till on Sunday

If the dramatic, rigorous monotony of farming does in fact amount to a form of meditation, in the clinical sense, then some recent research on the effect of meditation on the brain provides a ray of insight into why farming – and gardening – can make you a better person. It has to do with the possible effects of meditation on the brain’s cortex.

A thinner cortex, in certain areas of the brain, correlates with lack of empathy and a greater risk of depression. There is evidence that people who meditate regularly have a thicker cortex, the outermost layer of the brain. Thus, it wouldn’t surprise me if farmers have thicker cortexes than the average pencil-pusher, like me. It could make farmers less susceptible to depression and more even keeled.

Luckily I have my garlic mandala, formerly known as my garden, to fall back on. It’s basically a garlic patch with a year’s supply of garlic that, planted six inches apart in fall, I harvest the next summer. Each spring, I toss an assortment of seeds between the emerging garlic plants. Carrots, radicchio, amaranth, romaine, corn, melon, borrage ... basically whatever seeds I have lying around, I toss them in and see what happens. If the plants they code for don’t belong, they die. The ones that live in the shade of the garlic plants take off in July when the garlic is pulled.

The garlic mandala comes and goes, leaving a stash of bulbs in its wake. Does it also make me a better person? I like to think so. It certainly makes me a happier person. Whether its because I have a thicker cortex, or because I just love garlic, is a question I’ll leave to the poets and scientists.

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel