|

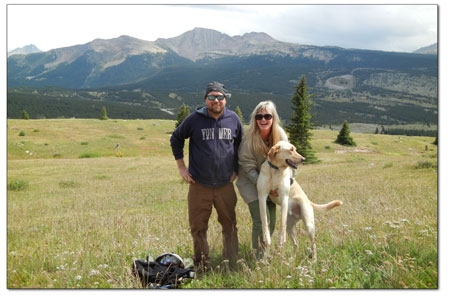

| Bryan Fryklund and Jen Reeder, along with their dog, Rio, celebrate Reeder’s 41st birthday on Aug. 24 on a hike above Little Molas Lake. Reeder, who “rocks one kidney” after giving hers to Bryan last summer, recently launched Rock One Kidney, a site to spread awareness and ease fears of donating kidneys./Courtesy photo |

Rockin’ one kidney

Local woman starts nonprofit to raise awareness for donations

by Missy Votel

Jen Reeder will never be able to kick box again. But it’s small price to pay for saving her husband’s life.

“Fortunately, it’s not an issue, since I never tried nor have I ever wanted to try kickboxing,” said the Durango West resident, who would rather spend her time hiking with husband, Bryan Fryklund, and their yellow lab, Rio.

It is that sense of humor that helped bring Reeder and Fryklund, both 41, from near-catastrophic kidney failure in 2012 to the near-normal lives they live today.

“The best piece of advice I got was ‘keep it light,’” said Reeder. “We joked around and tried not to think about it too much.”

|

Kidneys by the numbers -119,348: Americans awaiting organ transplant (all organ types) -97,270: Americans awaiting kidney transplant -1,661: Coloradans awaiting kidney transplant -6,000: Americans who died in 2012 awaiting kidney transplants -82: Coloradans who died in 2012 awaiting kidney transplants -6,000: Living donations now occurring each year in the U.S. (all organ types) -33: Overall living kidney donors in Colorado, 2013 About donations: Living donors are never paid, but the Denver-based American Transplant Foundation will help compensate donors with wages, rent, food and other expenses while they are recovering. There are four kidney transplant centers in Colorado: Children’s Hospital University of Colorado Porter Adventist Presbyterian St. Luke’s

|

The advice seemed to work. In fact, aside from the slew of medications Fryklund must now take daily, including anti-rejection drugs, he says life is pretty much “back to normal.”

Oh, except that instead of having two kidneys, he now has three. “As far as I can tell, I’m all better,” he said.

Now, more than a year since Reeder donated her kidney to Fryklund at Porter Adventist Hospital in Denver, it is that message of hope she is trying to spread to others. This month, Reeder launched Rock 1 Kidney, a nonprofit with the goal of dispelling misconceptions and fears surrounding kidney donation and sharing success stories from other donors.

“Knowledge is power,” said Reeder “It’s important to point out, kidney donation is not for everybody, it’s not perfect. But fear from lack of knowledge is no reason not to donate a kidney.”

Statistically, donors live longer than the general population, with less than 1 percent experiencing complications, Reeder said. “It’s a wonderful trick of evolution that we only need one kidney but are usually born with two,” she said. “I’ve never met a kidney donor who has regretted the decision to donate. It’s incredibly rewarding to give the gift of life to someone.”

According to the National Kidney Registry, nearly 100,000 Americans are currently awaiting kidney transplants, with 6,000 dying last year while waiting. In Colorado, more than 1,660 people await a kidney, with an average wait time of 11 months. And while Colorado is one of the most generous donor states, someone still dies on average every four days.

“I’m very, very happy and grateful that ours worked out, and I’m sad that so many people have to wait or lose their lives while waiting,” said Reeder.

That waiting game is one Reeder and Fryklund know all too well. Fryklund first started exhibiting symptoms of kidney problems in 2007, when the couple, who own a home in Durango, was living in Hawaii. A nephrologist soon confirmed their worst fears: Fryklund was diagnosed with IgA nephropathy, an incurable kidney disease. Believed to be autoimmune, the body basically turns on itself, attacking its own tissues, in this case the kidneys.

Although it can strike anyone at any time, it is most common among Asian and white men. One of the most common diseases of the kidney, other than diabetes and high blood pressure, about 25 percent of adults with IgAN develop total kidney failure, requiring dialysis or a kidney transplant.

Upon hearing the news, the couple left the Big Island, where there was only one nephrologist, and settled in Denver, where they had more treatment options. Armed with the diagnosis, their luck again took a turn, this time for the better. The disease essentially went into remission for the next four years, and the couple eventually returned to Durango in 2010.

Unfortunately, as is often the case with autoimmune disease, Fryklund took a turn for the worse in 2011. His kidney function levels started plummeting.

That’s when the couple, along with Dr. Darren Schmidt, of Durango Nephrology Associates, started exploring options. Due to several reasons, dialysis was ruled out.

“You have better chances of accepting a transplanted kidney without dialysis, plus it takes a huge chunk of time,” said Reeder. “You have to sit in a chair for five hours, three times week. Bryan was in his late 30s, that’s not an option when you like to hike with your dog, travel and be active.”

All roads began leading to a transplant. Knowing 4 they were not a perfect blood match – she’s O negative and he’s A negative – Reeder began researching paired donation, where she would donate a kidney to someone with O negative blood and that recipient would supply a donor for Bryan with A negative blood.

However, paired donation wasn’t ultimately necessary. Reeder learned that being O negative, she was a universal donor, and could give Bryan a kidney, granted she passed all the physical tests, which she did.

“I was in Las Vegas celebrating a friend beating breast cancer when I got the call,” she said. “We both burst into tears and hugged, and I called Bryan and burst into tears again.”

Soon after, Bryan’s kidney function dropped below 20 percent, and they scheduled the transplant for July 20, 2012, in Denver – a month shy of Reeder’s 40th birthday.

“There was no midlife I’m-turning-40 crisis for me,” she said. “Suddenly, we weren’t living with this shroud of fear, it was nice to start a new chapter.”

Surrounded by family and friends, the two emerged several hours later extremely sore, but happy.

|

|

Reeder and Fryklund share a moment to compare wristbands prior to surgery./Photo by Sally Reeder |

“It was intensely painful, and I remember taking a lot of naps, which I never do,” said Reeder.

Within a few days, the couple returned to a nearby (and well-scrubbed, thanks to friend Ali Baird and Reeder’s mom, Sally) hotel where they could be joined by Rio during their monthlong convalescence. Strangely enough, perhaps the most painful part of the entire ordeal was what got the couple through in the first place.

“The hardest part was, it hurt to laugh,” Reeder said. “My brother called, and he is really funny. I actually had to hang up on him because he was making me laugh.”

And while Reeder and Fryklund are the first to admit kidney donation is no laughing matter, they assert it is nothing to fear, either. A few months after their one-year “transplant-iversary,” they are living their lives to the fullest. They took a trip to the U.K. last spring to celebrate Fryklund’s recovery and recently attended the Phish shows in Denver.

“Our lives are very full, nothing’s changed, except maybe there’s more a sense of living your life,” Reeder said. “That’s the reason I wanted to start Rock One Kidney. Everyone kept saying before the surgery, ‘That’s great that you’re doing that for Bryan, but what’s it going to do to you?’”

Well, for now, the answer is a resounding “nothing” – although the couple admits there is one organ that has undergone an unexpectedly huge change: the heart.

“It’s brought us even closer together,” said Reeder. “After being together 20 years, I didn’t think we could get closer but we did. It was a small price to pay to save the love of your life’s life.”

Fryklund, who is understandably humble about the situation, agrees. “I like to say now that I have a pound of her flesh inside,” he said. “I can actually feel it. I’m constantly aware of where it is. It’s crazy.”

For more information or to read other kidney donor’s stories, visit www.Rock1Kidney.org.

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel