|

|

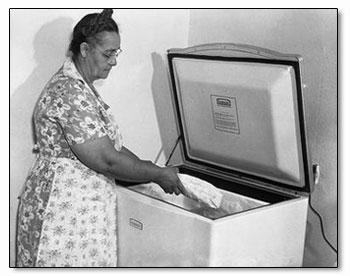

Warming up to frozen beefby Ari LeVaux This belief, and retail efforts to cater to it, are misguided. If processed correctly, frozen meat is just as good as fresh. And it has advantages, like the fact that it won’t spoil in a few days. And with grass-fed beef, depending on what time of year the animal is slaughtered, frozen could very well be more nutritious than fresh. Scott Barger, of Mannix Bros Ranch in Montana, told me he prefers to slaughter his cattle mid-summer, when feed quality is at its highest. “This would offer our customers the most healthy product, from a nutritional standpoint, because of the high omega-3s, the conjugated linoleic acids, and other benefits of grass beef that come from our animals eating a living product. When you remove those animals from eating live feed and put them on a stored feed ration, those nutritional levels in the meat go down.” In terms of meat quality, once the diet switches to hay at the end of summer, it’s downhill till springtime. The marble, that prized feature of good beef, is the first to go. “Marbling takes time to accomplish, but can be lost quickly,” Barger said. Feedlot beef producers don’t have these concerns. They can keep their animals fat all winter long with relative ease by feeding them grain. To them, selling meat fresh is the way to go, because it allows for year-round production at full-throttle, with no extra steps like freezing. The grass-fed beef industry, on the other hand, suffers from the idea that frozen meat is inferior to fresh. In most supermarkets, fresh meat is prominently presented in shiny display cases while frozen meat, if there’s any for sale at all, lurks down the frozen-food aisle. The only way grass-fed beef producers can get any visibility for their product in a supermarket is to supply fresh beef for that display case. To do so, grass-fed beef producers would have to maintain a year-round supply of market-sized animals ready for slaughter. This reality broke a once-promising relationship between Whole Foods and Wyoming’s Arapaho Ranch in 2010. Arapaho Ranch’s cattle graze on native grasses at the foot of the Wind River Mountains, and are tended by Native American cowboys on horseback. This pristine, romantic setting seems exactly the kind of thing that Whole Foods shoppers would be eager to buy into. But the arrangement folded in its first year, thanks to Whole Foods’ need – based on customer preference – for fresh beef through the winter. As the winter of 2010-11 wore on, the animals at Arapaho Ranch inevitably began to shrink. As they became lighter, the ranch received less money per animal. In addition to feed costs, there were labor, medical and other costs associated with keeping market-size animals alive through winter, and these all bit into profits. At the same time, winter storms made it difficult for the ranch to ship its animals, first to slaughter and then to Whole Foods’ regional hub in Denver. The arrangement became untenable for Arapaho, and Whole Foods wouldn’t budge on the price – fresh grass-fed beef was available from California or Florida. So while ranchers of grass-fed beef in those states might be helped by the American fixation with fresh meat, ranchers who operate anywhere there is winter are hurt by the fixation with fresh meat. Whole Foods’ meat coordinator for the Rocky Mountain region, David Ruedlinger, told me, “If we could get shoppers to buy beef at the peak of the season and freeze it themselves, or buy frozen product off-peak that was harvested at peak season, all these problems would be solved.” Because frozen beef doesn’t get much love at grocery stores, ranchers in cold regions who want to slaughter at the optimal time have little choice but to market their beef frozen, through the mail. Transactions like this are good for the rancher in that there is no middleman. But the consumer has to pay the high price of express shipping. And there is a karmic cost to burning so much carbon for the convenience of next-day frozen steak. If there were demand for frozen beef from grocery stores, they could make bulk shipments of frozen meat to retail outlets. They would be giving up a cut to a middleman, but it could be a lot less work then mailing away your animals piece by piece. If frozen meat were the supermarket norm, the grass-fed beef industry would have a lot more room to operate. But this could only happen if consumers were willing to make lifestyle adjustments. Switching to frozen meat would mean more than just a walk down a new supermarket aisle. It would require meal-planning that factors in defrost time. Adjusting to frozen meat would also mean getting savvy about distinguishing well-frozen meat from poorly frozen. Avoid frozen meat that’s wrapped in paper such that you can’t see what’s inside, because you have to see what it looks like in order to make an informed assessment. Properly frozen meat should be wrapped in tight plastic that hugs the meat, leaving no airspace where ice crystals can form. Stay away from any meat that’s discolored or has ice or air inside. Make note of the packing date, and make sure and use the meat before it’s a year old. et frozen beef thaw slowly, ideally overnight, as thawing too quickly can destroy a good piece of meat. No microwave or hot water, ever. The fastest I will thaw frozen meat, if I’m in a total hurry, is in a pot of cold water, in its packaging. |

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel