|

|

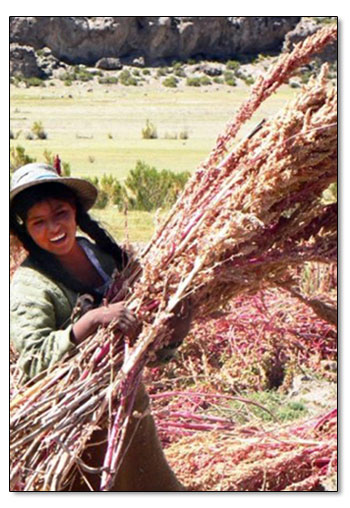

It’s OK, you can eat quinoaby Ari Levaux “The appetite of countries such as ours for this grain has pushed up prices to such an extent that poorer people in Peru and Bolivia, for whom it was once a nourishing staple food, can no longer afford to eat it.” This was one of several stories in the last few years published by the likes of NPR, Associated Press, and the New York Times. Some, like the Guardian, went to the extreme of guilt-tripping readers against buying imported quinoa. The idea that worldwide demand for quinoa is causing undue harm where it’s produced is an oversimplification at best. At worst, discouraging demand for quinoa could end up hurting producers rather than helping them. Most of the world’s quinoa is grown on the altiplano, a vast, cold, windswept and barren 14,000-foot Andean plateau spanning parts of Peru and Bolivia. Quinoa is one of the few things that grows there, and its high price means more economic opportunities for the farmers in one of the poorest parts of South America. An analysis by Emma Banks for the Andean Information Network responds to many of these quinoa questions with nuance largely absent from the press reports. “The impact of rising food prices is complex and encompasses food security and sovereignty debates,” Banks wrote. Food security means having enough to eat, while food sovereignty means having a voice in the food system. These are impacted differently in different places by increasing prices. But some generalizations can be made. Quinoa fetches a guaranteed high price affording farmers economic stability. This economic power has also translated into political power though producers’ associations and cooperatives, she explains. Since the 1970s, these organizations have worked toward greater producer control of the market, spurring other political actions such as blockades and protests for greater economic and environmental rights in quinoa-growing regions. Relevant to the food security discussion, though absent in all of the recent quinoa press coverage, is the fact that, as Banks notes, “Bolivian government nutrition programs have begun to incorporate quinoa into school breakfast and new mothers’ subsidies.” Similar programs are under way in Peru, New York Times reporter Andrea Zarate told me by phone from Lima. Edouard Rollet is co-founder of the fair-trade import company Alter Eco, which deals in Bolivian quinoa. His company works with 1,500 families in about 200 Bolivian villages. “I’ve been going to the altiplano once or twice a year since 2004,” Rollet told me by phone. “The farmers are still eating quinoa.” He said that over the years he’s watched how the extra income from rising prices has allowed the families he works with to diversify their diets dramatically, adding foods like fresh vegetables. Those hit hardest by the rising price of quinoa are probably quinoa eaters who live in urban areas, since they must pay higher prices, but don’t reap the benefits. This is especially true for those who have moved to the city from the countryside, and are used to having access to quinoa but can no longer afford it. At the same time, rising prices are drawing many refugees back to the countryside, where it’s now possible to make a living from farming. In her analysis, Banks points out that while quinoa farming has for years received state support in Peru, in Bolivia it’s largely been a grassroots effort, with producers organizing and collecting the necessary equipment to process seeds and bring back quinoa real, the most commercially viable variety of quinoa. The UN declared 2013 the International Year of Quinoa, saying it has the potential to advance food security. In fact, quinoa is so complete that NASA is considering it as astronaut food for long space rides. While attempts to grow quinoa haven’t worked out in Britain, Locovores in the U.S. can take heart at the fact that farmers in Oregon and Colorado are figuring out how to grow it. That said, domestic quinoa sells out quickly after every harvest, so for the time being quinoa lovers will be importing most of theirs from the altiplano. And that’s a not a bad thing. Wherever it’s grown, concerns about buying imported quinoa are overblown. The Guardian calls it “a ghastly irony when the Andean peasant’s staple grain becomes too expensive at home because it has acquired hero product status among affluent foreigners.” There is, in fact, a ghastly irony here. It’s when media stories discourage people from buying imported quinoa in the name of solidarity with locals. But instead of helping, such reports threaten to kick the legs out from under one of the most promising industries in one of the world’s poorest places. |

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel